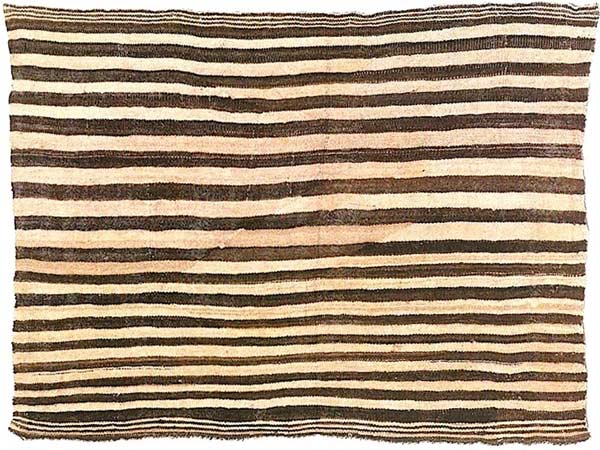

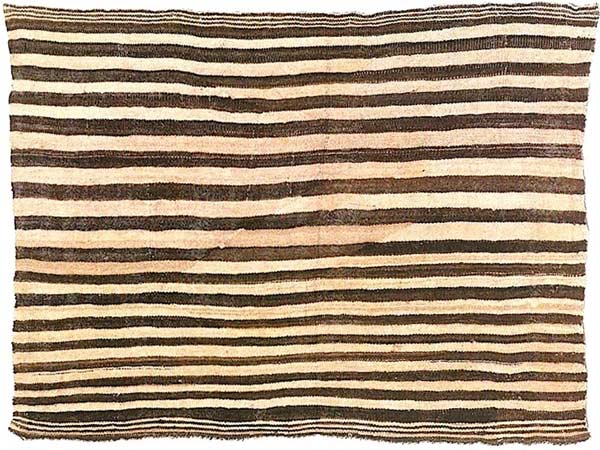

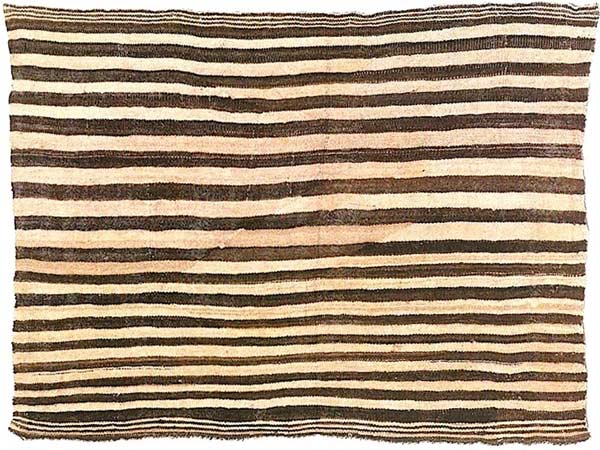

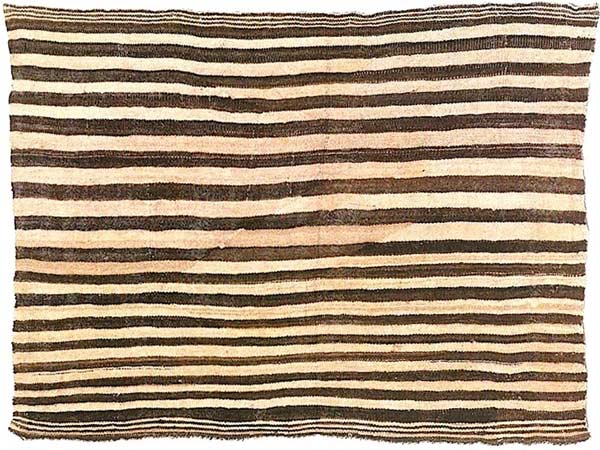

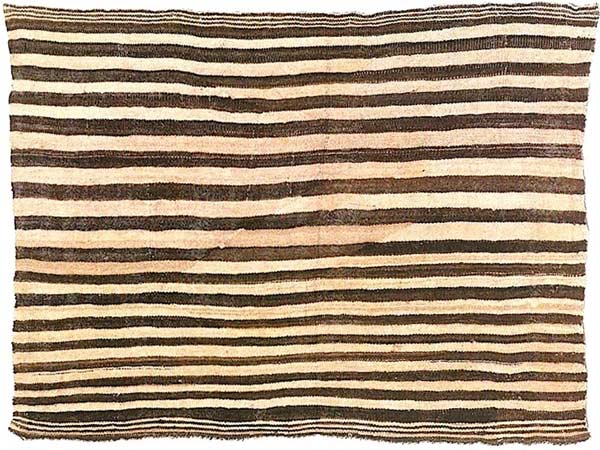

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style,

Navajo, circa 1750-1800, also known as the Morris First Phase.

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1750-1800, also known as the Morris First Phase.

The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

The Morris First Phase is illustrated as Plate 49 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund describe the first phase as “Navajo Shoulder Blanket (1750-1880), Banded,” and note that it was “Collected in 1937 by Earl H. Morris and Alfred V. Kidder from a Navajo grave in Canyon de Chelly.” “1750” is the earliest circa date assigned by Wheat and Hedlund to a Navajo chief’s blanket.

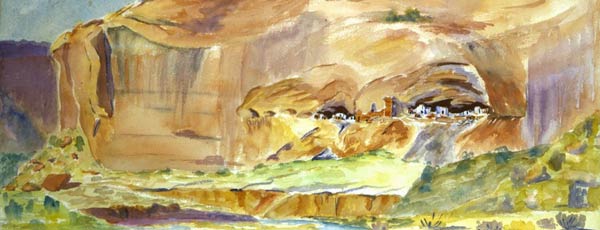

The Morris First Phase is also illustrated as Plate 63a in Amsden, Navaho Weaving, Its Technic and Its History, 1934. Amsden does not date the first phase, but suggests it could have been woven as early as “the year 1800.” The illustration in Amsden raises the question: If Morris and Kidder collected the first phase in 1937, how can it be illustrated in a book published in 1934? During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Morris and Kidder worked together on the reconstruction of the sandstone tower at Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto. They may have excavated the first phase from a burial at Mummy Cave, prior to 1934.

The Morris First Phase is in the collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC), in Santa Fe, by donation from Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder. MIAC classifies the Morris First Phase as a grave good. The first phase is available for viewing only to Native Americans. [MIAC Catalog #9150/12.]

Above: The Morris First Phase, Navajo, Woman’s Style circa 1750-1800.

In the collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe,

by donation from Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder.

Above: The Morris First Phase, Navajo, Woman’s Style circa 1750-1800. In the collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe, by donation from Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder.

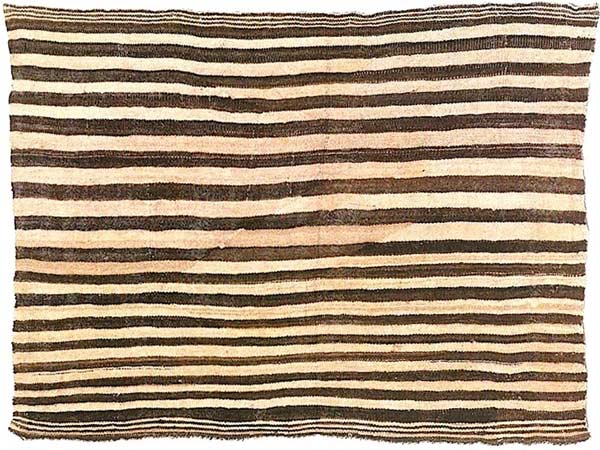

Below: The Taylor First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860.

In the collection of the Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs,

by donation from Alice Bemis Taylor.

Below: The Taylor First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860. In the collection of the Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs, by donation from Alice Bemis Taylor.

The Morris First Phase does not follow the traditional format of a classic first phase chief’s blanket woven in either the man’s or the woman’s style. It has no central panel. There are no pairs of blue bands running horizontally through its top or bottom panels. Ticking appears in the thin stripes in the top and bottom panels, and in some of the brown and white bands in the field. The Morris First Phase, the Schoch First Phase, and the Manchester Bayeta First Phase, Woman’s Style, are the only known classic first phases with ticking in their horizontal bands.

A possible explanation for the Morris First Phase’s departure from the traditional first phase format is that, between 1750 and 1800, the format did not exist. The Morris First Phase may not deviate from the traditional first phase format so much as it was woven before the format became established.

Condition of the Morris First Phase is 95% original, with wear to its top and bottom edge cords. Corner tassels are missing. Side selvages are 50% intact. Stains are visible in the field. One fold line runs vertically through the center. For a blanket with a circa date of 1750, the first phase is in extraordinary condition.

In the Morris First Phase, the blue yarns—in the thin blue stripes at the top and bottom of the first phase—are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece, from at least two different fleeces. The white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece, from at least two different fleeces. The darker of the two white handspun yarns is an variegated pale beige. The lighter of the two white handspun yarns is consistent in color with the handspun ivory white yarns that appear in early classic first phases, like the Cahn First Phase and the Morgan First Phase.

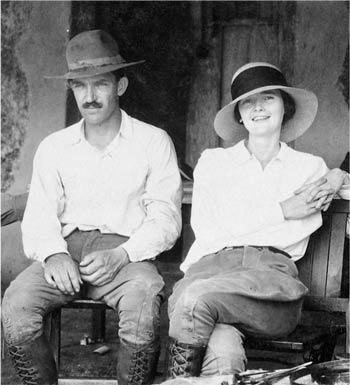

Earl Morris and Ann Axtell Morris, Chichen Itza, 1924

Earl Halstead Morris (1889-1956) was an American archeologist renowned for his contributions to Mesoamerican and southwestern archaeology, including his excavations of the Mayan ruins at Chichen Itza in the Yucatan, and of the Great Kiva in Aztec, New Mexico. In the late 1970s, Morris, his leather boots, and Stetson hats were among the inspirations for Indiana Jones’s character in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Morris’s father, Scott Neering Morris, collected Native American prehistoric objects. Earl Morris's interest in archaeology began in 1912, when he met Dr. Edgar L. Hewett on a train. Later that year, Morris began his first field excavation in the La Plata district in southwestern Colorado. In 1914 and 1916, Morris received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in psychology from the University of Colorado in Boulder. Between 1916 and 1923, Morris supervised excavations at the Great Kiva in Aztec, New Mexico. His excavations were sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History.

Between 1924 to 1929, Morris was director of excavations at Chichen Itza, on the Yucatan Peninsula. His excavations were sponsored by the Carnegie Institution. Between excavations at Chichen Itza, Morris excavated at Canyon de Chelly; at Anasazi sites near Shiprock, New Mexico; at Mogollon sites in the Mimbres Valley in Grant County, New Mexico; and at Antelope Mesa on the Hopi Reservation.

In 1923, Earl Morris married the archaeologist, Ann Axtell. The couple spent their honeymoon at Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto. Ann Axtell Morris told her friends the wedding announcement should have read, “Mr. and Mrs. Earl Halstead Morris at home (in a tent), Canyon of the Dead, Arizona, September, 1923.”

Mummy Cave, Canyon de Chelly, 1923

by Ann Axtell Morris (1900-1945)

Watercolor on paper

Mummy Cave, Canyon de Chelly, 1923 by Ann Axtell Morris (1900-1945). Watercolor on paper.

Ann Axtell Morris became Earl Morris’s partner in field work and research. During the 1920s and 1930s, the couple traveled throughout Mexico and the southwest. Ann Axtell Morris played a key role in the documentation and reconstruction of the Temple of the Warriors at Chichen Itza.

The Morrises had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann and Sarah Lane. Elizabeth went on to get a degree in Anthropology from the University of Arizona. Ann Axtell Morris died in 1945, after a long illness. In 1947, Morris re-married, to Lucile Bowman.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Earl Morris supervised restorations of the sandstone tower at Mummy Cave, in Canyon del Muerto; of the Great Kiva at Aztec Ruins National Monument; and of several structures in Mesa Verde National Park. In 1931, the University of Colorado awarded Morris the Norlin Medal. In 1942, Morris received an honorary Doctor of Science degree. In 1953, Morris was awarded the Alfred Vincent Kidder Award for excellence in the fields of southwestern and Mesoamerican archaeology.

In addition to his excavations and reconstructions of iconic ruins, Morris was an accomplished photographer. During his forty years in the field, Morris developed bodies of evidence that documented and organized a chronology of prehistoric southwest cultures. Morris’s chronology is presented in his book, Archaeological Studies in the La Plata District, published in 1939.

Morris’s collections of artifacts, correspondence, field notes, and photographs are held at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History (CUMNH) in Boulder, and at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. CUMNH also has the Earl H. Morris Archive, containing unpublished documents and photographs from Morris’s fieldwork and research.

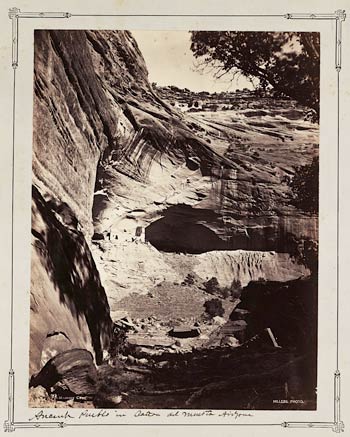

Mummy Cave, Canyon del Muerto, Arizona, 1880.

Cabinet photo by John Hillers.

Mummy Cave, Canyon del Muerto, Arizona, 1880. Cabinet photo by John Hillers.

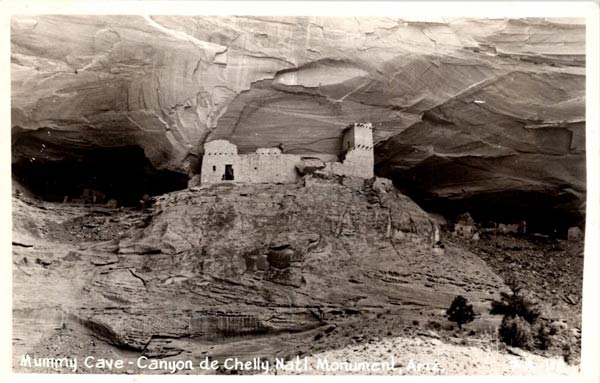

Mummy Cave - Canyon de Chelly Natl Monument, Ariz

Real photo postcard, post-marked October, 14, 1950.

Mummy Cave - Canyon de Chelly Natl Monument., Ariz. Real photo postcard, post-marked October, 14, 1950.

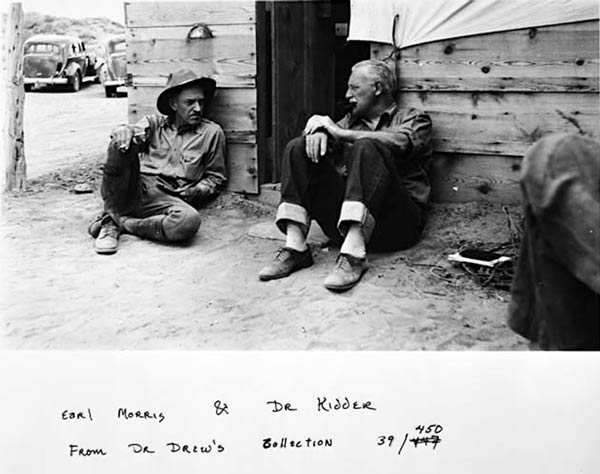

Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder, Antelope Mesa, 1939.

Antelope Mesa overlooks Canyon del Muerto and Mummy Cave.

Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder, Antelope Mesa, 1939. Antelope Mesa overlooks Canyon del Muerto and Mummy Cave.

“Earl, in from Boulder, met me at the Denver station - khakis, leather leggings,

stiff-brimmed Stetson - most dependable man the Lord ever made.”

“Earl, in from Boulder, met me at the Denver station - khakis, leather leggings, stiff-brimmed Stetson - most dependable man the Lord ever made.”

Alfred Kidder, 1938.

Alfred Vincent Kidder (1885-1963) was also a celebrated American archaeologist. Born in Marquette, Michigan, in 1885, Kidder was the son of a mining engineer. He entered Harvard College with the intention of qualifying for medical school but was bored and discouraged by pre-medical courses.

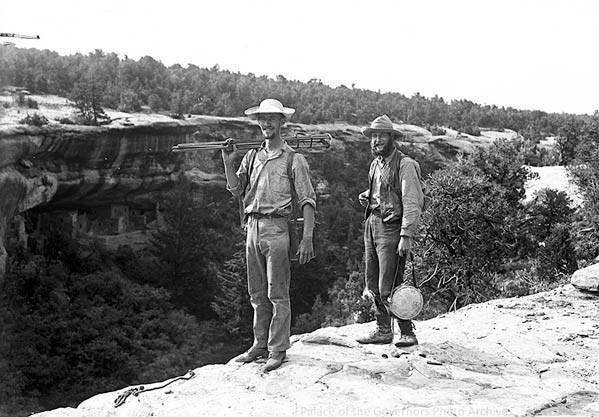

In 1907, Kidder applied for a summer job in archaeology with the University of Utah. He spent the next two summers in the canyon country of southwestern Colorado, southeastern Utah, and northwestern New Mexico. In 1908, Kidder and Jesse L. Nussbaum—later the Superintendent of Mesa Verde National Park—came to Mesa Verde with the ethnologist Jesse Walter Fewkes to conduct archaeological surveys and to photograph Mesa Verde’s ruins. In 1908, Kidder got a bachelor's degree at Harvard, followed by a doctorate in Anthropology, in 1914.

Between 1915 and 1929, Kidder directed and made excavations at Pecos Pueblo near Pecos, New Mexico. The pueblo had been abandoned by the Jemez People in 1838. It is now the site of Pecos National Historical Park.

At Pecos Pueblo, Kidder excavated levels of human occupation going back more than 2000 years. He assembled a detailed record of cultural artifacts, including an extensive collection of pottery fragments. Through his analysis of the fragments, Kidder created a continuous record of pottery styles from 100 BC through the mid-1800s.

Kidder correlated changes and trends in pottery styles with changes and trends in the Pecos people's culture. His research developed chronologies for prehistoric, proto-historic, and historic southwest Pueblo eras. With Samuel J. Guernsey, Kidder worked out a detailed, chronological narrative of Pecos Pueblo’s cultural periods. Kidder was one of the first archaeologists to draw conclusions about the development of a Pueblo culture based on his examinations of the chronology and strata of that culture’s archaeological sites. His research laid the foundation for modern archaeological field methods.

Alfred Kidder and Jesse Nussbaum, Mesa Verde, 1908.

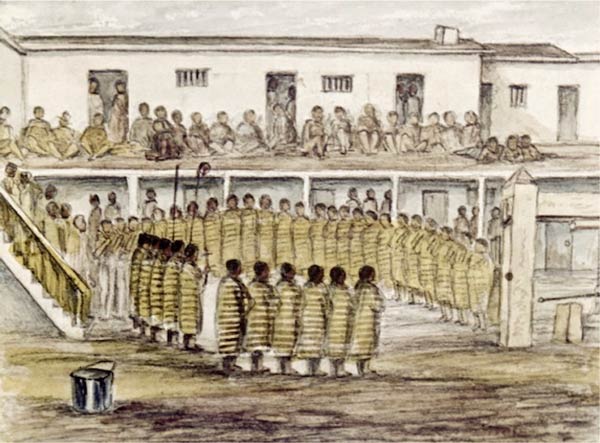

Cheyenne Scalp Dance at Bent’s Fort, Colorado, 1845.

Sketch by Lieutenant James W. Abert (1820-1897).

Cheyenne Scalp Dance at Bent’s Fort, Colorado, 1845. Sketch by Lieutenant James W. Abert (1820-1897).

James W. Abert was a painter, explorer, and officer with the US Army

Topographical Engineers. In 1845, Abert was attached to the Third Expedition

of Major John Charles Frémont, with orders to survey the Comanche

and Kiowa regions along the Canadian River in southwestern Colorado.

James W. Abert was a painter, explorer, and officer with the US Army Topographical Engineers. In 1845, Abert was attached to the Third Expedition of Major John Charles Frémont, with orders to survey the Comanche and Kiowa regions along the Canadian River in southwestern Colorado.

In his diary, Abert describes the Cheyenne women and their chief’s blankets: “In the afternoon I was kindly invited by the gentlemen of the fort to see a scalp dance. On going up, I found about 40 women with faces painted red and black, nearly all cloaked with ‘Navahoe’ blankets and ornamented with necklaces and earrings, dancing to the sounds of their own voices and the four tambourines which were beat upon them by the men.” (Abert’s Diary, 1845.)

In 1844 and 1845, William M. Boggs worked at Bent’s Fort, as a trader with the local tribes. Boggs was the son of Lilburn W. Boggs, the sixth governor of Missouri. In his Manuscript About Bent's Fort, dated 1905, William Boggs observes that the close weave and natural oil content of the wool in Navajo chief’s blankets made the blankets valuable to the Cheyenne because “These qualities made them waterproof.”

In his account of the same scalp dance at Bent’s Fort painted by James Abert, Boggs describes the Navajo chief’s blankets as “all alike, with white and black stripes[s] about two inches wide.” At the dance, Boggs watched “several hundred of these young Indian maidens, dressed in their Navajo blankets, form a circle at a war dance outside a circle of braves, who were dancing around a large bonfire with their trophies of Pawnee scalps.”

Abert’s sketch and quote, and Boggs’s quote, are the earliest Anglo-American references to first phases woven in the woman’s style, with thin, alternating brown and white stripes. The first phases worn by the Cheyenne women in Abert’s sketch show a strong resemblance to the format and striping pattern of the Morris First Phase.

Abert’s and Boggs’s quotes were referenced by Dr. Kathleen Whitaker in The Navajo Chief Blanket – A Trade Item Among Non-Navajo Groups, an articlethat appeared in the Winter, 1981, issue of American Indian Art Magazine.

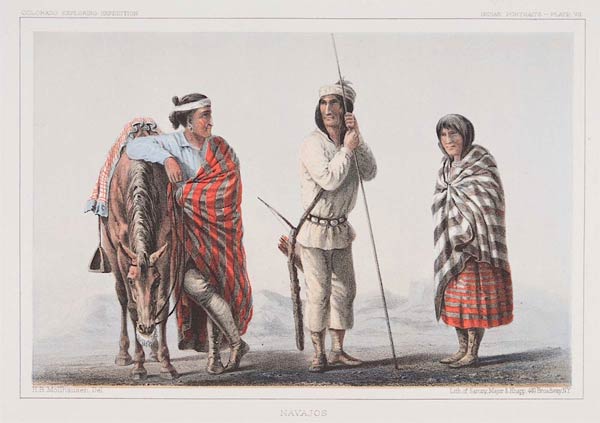

Navajos, by Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen, 1858.

The Navajo woman on the right is wearing what appears to be a first phase

woven in the woman’s style, with alternating brown and white stripes.

The Navajo woman on the right is wearing what appears to be a first phase woven in the woman’s style, with alternating brown and white stripes.

Like the Morris First Phase, and the first phases worn by the Cheyenne women

in James Abert’s 1845 sketch of the Scalp Dance at Bent’s Fort, the first phase

in Möllhausen’s drawing has no central panel and no pairs of blue bands.

Like the Morris First Phase, and the first phases worn by the Cheyenne women in James Abert’s 1845 sketch of the Scalp Dance at Bent’s Fort, the first phase in Möllhausen’s drawing has no central panel and no pairs of blue bands.

Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen (1825-1905) was a German artist, traveler, and writer. Möllhausen visited the United States during the 1850s. He was involved in three separate expeditions exploring the American frontier. In 1857, Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives of the US Army’s Topographical Engineers invited Möllhausen to join Ives’s exploration of the Colorado River and Grand Canyon. Möllhausen accepted. Ives appointed Möllhausen “artist and collector in natural history.”

In October, 1857, the Ives Expedition assembled in San Francisco. After proceeding to Fort Yuma, the expedition traveled for 530 miles up the Colorado River, first in The Explorer, a small steamer built specifically for the trip; then, after the river became shallow, on foot to the Grand Canyon. After exploring the Grand Canyon, the expedition headed east, reaching Fort Defiance, north of Zuni Pueblo, where it completed its explorations on May 23, 1858. Results of the Ives Expedition were published in 1861, in Ives’s Report Upon the Colorado River of the West. Möllhausen’s illustrations in Ives’s Report are among the first published views of the Grand Canyon.

A black-and-white illustration of Möllhausen’s Navajos appears on Page 119 in Amsden, Navaho Weaving, as Plate 57b.

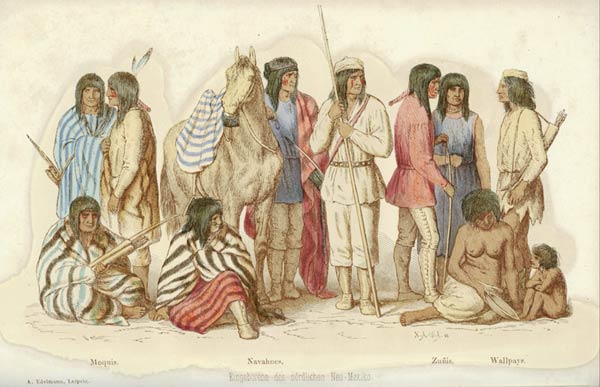

Indigenous People of Northern New Mexico, by Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen, 1858.

The drawing was published in 1861, in Ives’s Report Upon the Colorado River of the West.

Möllhausen identifies the three people on the far left as “Moquis;” the three people with the horse at the left center as “Navahoes;” the two people at the right, in red and blue garments, as “Zunis;” and the man, woman and child on the far right as “Wallpays.”

The Navajo woman seated directly below the horse is wearing what appears to be a first phase woven in the woman’s style, with alternating brown and white stripes. Her deerskin boots and red and brown dress suggest that she may be the same Navajo woman who appears in Möllhausen’s Navajos.

Like the Morris First Phase, and like the first phases worn by the Cheyenne women in James Abert’s Cheyenne Scalp Dance at Bent’s Fort, Colorado, 1845, the first phase in both of Möllhausen’s drawings appears to have no central panel and no pairs of blue bands. While it’s not possible to know how faithful Möllhausen’s original drawing was to the first phase being worn by the Navajo woman in the drawing, his depictions of the first phase in Navajos and the first phase in Indigenous People are consistent with each other, and with the format of the Morris First Phase.

The Morris First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1750.

The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 50 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase, Navajo, circa 1800-1830. The first phase measures 50 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase was collected in St. Louis between 1833 and 1837 by Lorenz Alphons Schoch of Bern, Switzerland. It is the only known example of a classic Navajo chief’s blanket, man or woman’s style, woven without blue handspun yarns. It is also the earliest Navajo blanket with documented collection history.

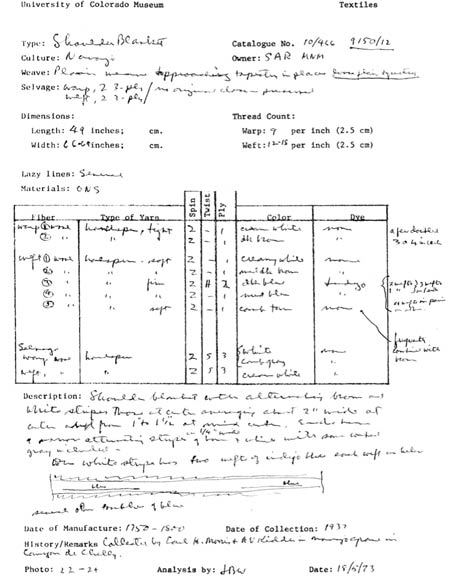

Dr. Joe Ben Wheat’s handwritten analysis of the Morris First Phase.

Wheat lists the first phase’s Date of Collection as “1937.” Under History / Remarks,

Wheat notes that the first phase was “Collected by Earl H. Morris + A V Kidder

in Navajo grave in Canyon de Chelly.” Wheat’s analysis is dated “18/5/73.”

Dr. Joe Ben Wheat’s handwritten analysis of the Morris First Phase. Wheat lists the first phase’s Date of Collection as “1937.” Under History / Remarks, Wheat notes that the first phase was “Collected by Earl H. Morris + A V Kidder in Navajo grave in Canyon de Chelly.” Wheat’s analysis is dated “18/5/73.”

During the 1920s, Charles Avery Amsden (1899-1941) was Superintendent and Treasurer of the Southwest Museum in Pasadena. Between 1930 and 1933, Amsden wrote Navaho Weaving – Its Technic And Its History, the first comprehensive book about Navajo blankets. (Spellings are Amsden’s.)

Navaho Weaving was published in 1934, by Rio Grande Press. For many collectors, dealers, and scholars, the illustrations in Navaho Weaving were their introductions to classic chief’s blankets and classic serapes. Amsden’s survey of historic Navajo weaving remains a vital source of information for anyone who wants to understand why Navajo blankets are an important part of American art and American history.

The following quote appears on page 132 of Amsden’s Navaho Weaving, as a caption to Plate 63a., the Morris First Phase.

Old Navaho shoulder blanket. Size 66 x 48 ins., colors natural brown and white with a single strand of indigo blue. Found buried in a cave cist with the mummified body of a tall, spare man. His hair was tied in a hank and he wore deer skin leggings with woven garters, and a woven shirt. With the burial were buffalo and deer skins and the shoulder mantle or dress of Pueblo (woman’s) type, black with indigo blue border in diamond twill, size 63 x 45 ins., shown in b; yet the man was Navaho, the burial in Navaho territory.

To assign these specimens to about the year 1800 seems no exaggeration in view of all circumstances.

Old Navaho shoulder blanket. Size 66 x 48 ins., colors natural brown and white With a single strand of indigo blue. Found buried in a cave cist with the mummified body of a tall, spare man. His hair was tied in a hank and he wore deer skin leggings with woven garters, and a woven shirt. With the burial were buffalo and deer skins and the shoulder mantle or dress of Pueblo (woman’s) type, black with indigo blue border in diamond twill, size 63 x 45 ins., shown in b; yet the man was Navaho, the burial in Navaho territory.

To assign these specimens to about the year 1800 seems no exaggeration in view of all circumstances.

The Morris First Phase is one of the earliest examples of classic Navajo weaving. It

may be one of the first Navajo blankets woven in the first phase style. Its alternating brown and white bands, and the absence of pairs of blue bands, link the Morris First Phase to the Schoch First Phase, which also has brown and white bands but no pairs

of blue bands. The presence of ticking in the Morris First Phase and the Schoch First Phase—the earliest Navajo blanket with documented collection history— seems beyond coincidence.

James Abert’s 1845 sketch of Cheyenne women wearing first phases during the scalp dance at Bent’s Fort; Abert’s and William Boggs’s written accounts of the same scalp dance; and H. B. Möllhausen’s 1858 drawings of a Navajo woman wearing a woman’s style first phase establish that woman’s style first phases were worn by Navajo women and by women from other tribes. This confirms that the woman’s first phase style remained popular from 1750 through 1845, and possibly through 1858.

The Morris First Phase was collected by Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder, two prominent figures in the history of American archaeology. Morris and Kidder collected the first phase at Mummy Cave in Canyon del Meurto, in what is now the Canyon De Chelly National Monument. Mummy Cave is one of the most significant archaeological sites in the southwest. Canyon de Chelly is sacred ground to the Navajo people. Morris’s and Kidder’s donation of the first phase to the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, in Santa Fe, confirms that the two anthropologists considered the first phase important enough to donate it to a major public institution.

The Morris First Phase is a simple blanket. It’s simplicity speaks of an era when Navajo women wove composure and restraint into their blankets. The first phase’s collection history and status as a burial item make it a more complicated blanket. Each classic first phase comes with its own set of paradoxes. Any effort to appreciate Navajo first phases would be incomplete without an effort to appreciate the Morris First Phase.