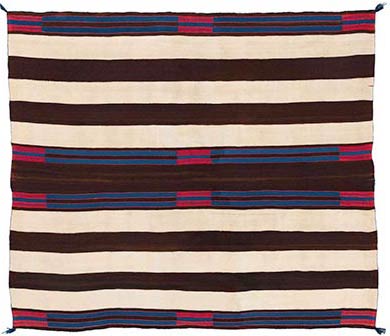

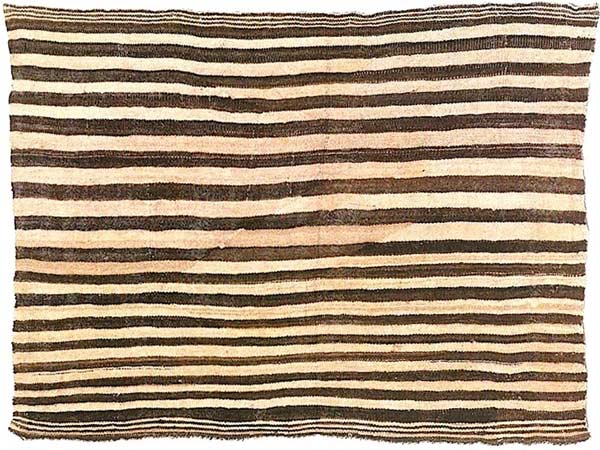

A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo,

circa 1800-1830, also known as the Morgan First Phase.

A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1800-1830, also known as the Morgan First Phase.

The first phase measures 52 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

What Is A First Phase?

One of the first things people learn about Navajo chief’s blankets is how to identify a first phase. If a chief’s blanket has designs, it’s either a second phase, a third phase, or a variant. If a chief’s blanket has horizontal bands and stripes, but no designs, it’s

a first phase.

Top Left: The Berlant First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1840

Top Right: The Chantland Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840

Lower Left: The Taylor First Phase, Ute Style, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860

Lower Right: The Buffaloe Bayeta First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1855

Classic (pre-1860) first phases woven in the man’s style have alternating brown and white bands above and below their central panels, with pairs of blue stripes in their top, bottom, and central panels. The average dimensions for a man’s style first phase are 60 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

Classic first phases woven in the woman’s style have thin, alternating stripes above and below their central panels, with pairs of blue stripes in their top, bottom, and central panels. Their thin, alternating stripes are either brown and grey or brown and white. The average dimensions for a classic first phase, woman’s style, are 45 inches long by 55 inches wide, as woven.

Ute Style first phases have no red stripes. Bayeta first phases have thin red stripes. While Ute Style first phases are the earlier style, it would be a mistake to assume that all Ute Style first phases were woven before all bayeta first phases.

Upper Left: A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1830

Upper Right: A Classic Bayeta Second Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850

Lower Left: A Classic Bayeta Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850

Lower Right: A Classic Chief’s Blanket Variant, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1840

What Is a Chief’s Blanket?

Classic Navajo chief’s blankets were woven between 1750 and 1860. Like Navajo mantas, chief’s blankets were woven wider-than-long, as opposed to Navajo serapes, which were woven longer-than-wide.

While some chief’s blankets were woven for Navajo men and women, the majority were woven as trade items and then bartered to ranking members— or chiefs—of the Arapahoe, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, Shoshoni, or Ute tribes. Between 1800 and 1870, Plains and Prairie men and women wore chief’s blankets around their shoulders, as robes. By 1840, the chief’s blanket had replaced the painted buffalo robe as the most valuable trade item in North America, and was accepted as a store of value and a form of currency throughout the Southwest, the Great Plains, the Prairie, and the Missouri Valley.

A Banded Cotton Manta, Ancestral Puebloan / Anasazi, circa 1100, A.D.

The manta measures 44 inches long by 47 inches wide, as woven.

A Banded Cotton Manta, Ancestral Puebloan / Anasazi, circa 1100, A.D. The manta measures 44 inches long by 47 inches wide, as woven.

What Are the Origins of the First Phase?

This prehistoric cotton manta was discovered during the 1970s at an Ancestral Puebloan / Anasazi ruin near Wallace Tank, east of Holbrook, Arizona. The Wallace Tank Ruin is one hundred miles southeast of Hopi Pueblo.

The manta was found in a large ceramic jar with a stone lid covering the top of the jar. There were three other cotton mantas in the jar.

During the late 1990s, Anne and Bill Ziff, of Aspen, purchased the manta from William Siegal, of Santa Fe. During the late 1990s, the manta was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, by loan from Anne and Bill Ziff. The manta is in the collection of Anne Ziff, of New York.

There is a related Ancestral Puebloan / Anasazi cotton manta in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), by donation from Paul Cahn, of Saint Louis, in 2018. The MIA manta is also one of the four prehistoric cotton mantas found in the ceramic jar at the Wallace Tank Ruin, east of Holbrook, Arizona.

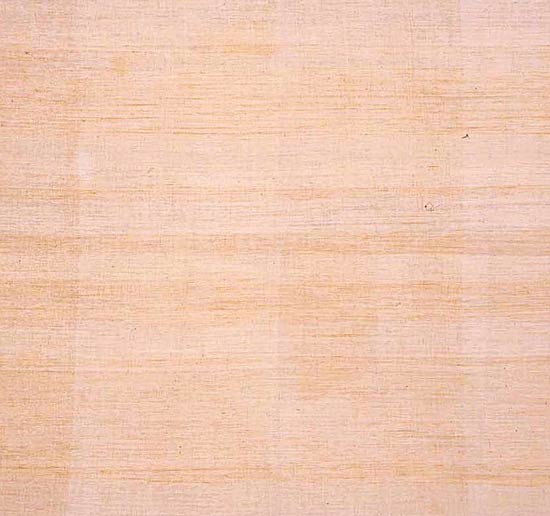

A detail of the center of the Banded Cotton Manta,

Ancestral Puebloan / Anasazi, circa 1100, AD.

A detail of the center of the Banded Cotton Manta, Ancestral Puebloan / Anasazi, circa 1100, AD.

All of the yarns in the prehistoric manta are un-dyed handspun cotton, from three distinct batches of beige cotton roving. The three cotton yarns range in color from

a dark beige to a medium beige to a pale beige. All three beige yarns were used as warps and wefts. The use of the three colors of beige both as bands of warp and as bands of weft creates a plaid effect in the field of the manta.

The dark, medium, and light colors of beige also appear as horizontal bands of weft. Three horizontal bands of the dark beige are visible across the center of the manta. Four horizontal bands of the pale beige separate the three horizontal bands of dark beige.

The manta’s banded, plaid effect is similar to the banded, plaid effect that appears in the Pösaala, or Hopi Bachelor Blanket. The Wallace Tank Ruin is one hundred miles southeast of the Hopi Reservation. Walpi, the oldest of the villages on First Mesa at Hopi Pueblo, was settled between 950 and 1100, AD.

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830, also known as the Schoch First Phase. The first phase measures 51 inches long by 70 inches wide,

as woven. The Schoch First Phase was collected in St. Louis between 1833 and 1837 by Lorenz Alphons Schoch of Bern, Switzerland. Schoch (1810-1866) was the son of

a Swiss instruments manufacturer. In Swiss-German, Schoch is pronounced “shock.”

The Schoch First Phase is the earliest Navajo blanket with documented collection history. It is the only classic Navajo chief’s blanket woven without blue yarns. The absence of blue yarns suggests that the Schoch First Phase may have been woven as

a Navajo version of the Pösaala, or Hopi Bachelor Blanket.

In 1833, Lorenz Schoch arrived in Saint Louis. For the next four years, he collected more than 100 works of Native American art, including Iron Horn’s War Shirt, the Mato Tope Buffalo Hide, and the Schoch First Phase. Many of the items Schoch collected were antique when he acquired them.

Schoch left St. Louis in 1837. By 1842, he had returned to Switzerland with the first phase and the rest of the items he had collected in Saint Louis. After Schoch’s death, in 1866, the collection remained with his family until 1890.

In 1890, the Bernisches Historisches Museum (BHM), in Bern, Switzerland, purchased all of the items in Schoch’s collection from Schoch’s widow, Marie Karolina Ruef. The Schoch First Phase is cataloged by the museum as a “Sioux trade cloth.” [BHM Catalog #1890.410.0027.]

BHM’s catalog description raises the possibility that Schoch collected the first phase from a member of the Sioux tribe and never identified it as a Navajo chief’s blanket. The catalog description also raises the possibility that the Bernisches Historisches Museum is unaware of the first phase’s status as the earliest known example of

a Navajo blanket with documented collection history.

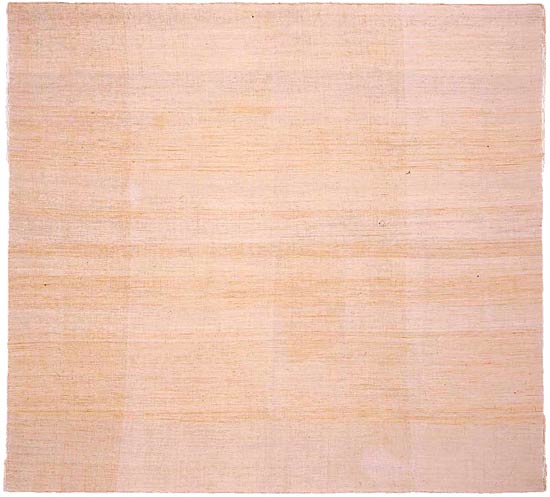

A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi

or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

The Pösaala measures 45 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

Dimensions are large for a classic Hopi Pösaala. The large dimensions raise the possibility that the Pösaala was woven by a Navajo woman who had married into

a Hopi family. The irregular widths of the Pösaala’s horizontal and vertical bands support the Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi attribution.

The Pösaala is fully twilled. The twilling appears as a diagonal pattern, as a diamond pattern, and as a herringbone pattern. While twill patterns are common in Hopi Pösaalas and Navajo mantas, the combination of three twill patterns in the same manta appears more often in classic Navajo mantas than in classic Hopi Pösaalas. Ticking, also called beading, appears in the two thin white lines that run horizontally across the Pösaala’s dark brown central panel.

The brown yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece, all from the same brown fleece. The white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece. The white yarns exhibit the ivory color that appears in classic Navajo chief’s blankets woven between 1800 and 1850. Like all of the other classic Pösaalas, or Hopi Bachelor Blankets, in museum and private collections, the Pösaala contains no blue yarns.

In August, 2017, the Pösaala was purchased from a private collector in Santa Fe, by Joshua Baer & Company. In October, 2017, the Pösaala was purchased by the current owner from Joshua Baer & Company.

Above: The Schoch First Phase, Navajo, circa 1800.

Below: A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi,

or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

Below: A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi, or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

The Schoch First Phase is the only classic Navajo chief’s blanket woven without blue yarns. The absence of blue yarns suggests that the Schoch First Phase may have been woven as a Navajo version of the Pösaala, or Hopi Bachelor Blanket.

An Early Classic Twilled Manta with Blue Borders

and a Brown Center, Navajo, circa 1750-1800.

An Early Classic Twilled Manta with Blue Borders and a Brown Center, Navajo, circa 1750-1800.

The manta measures 44 inches long by 47 inches wide, as woven.

The Navajo people arrived in the southwest between 1300 and 1450, A.D. The Navajos were a nomadic culture. Anthropologists and linguists link the Navajos to the Apache tribes, and to Athabaskan tribes in what are now Alberta, Alaska, and Siberia.

Sheep arrived in the Southwest in 1540, with the first Spanish explorers. Many anthropologists believe that Navajo women learned the art of upright loom weaving from Pueblo weavers after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. By the early 1700s, Navajo women were weaving woolen blankets designed to be worn around the body, like buffalo robes. By 1750, Navajo women were weaving twilled woolen shawls, known among the Spanish as mantas. Navajo mantas were woven wider- than-long, with brown central panels and blue borders.

Between 1750 and 1800, Navajo women started weaving a style of blanket with alternating horizontal brown and white bands. By 1800, Navajo women were weaving

a larger version of the blanket as a trade item, with alternating horizontal brown and white bands in the field, and pairs of blue stripes inside its top and bottom brown bands and its brown central panel.These blankets came to be known first phase chief’s blankets.

The similarities between the brown and white bands in the Pösaala, or Hopi Bachelor Blanket, and the brown and white bands in Navajo first phases raise the possibility that the earliest first phases were Navajo versions of the Hopi Bachelor Blanket.

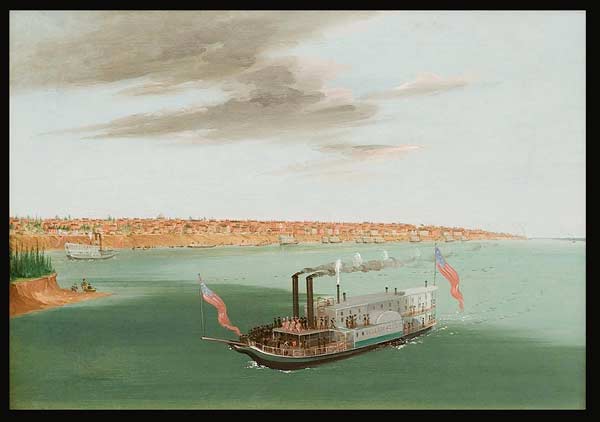

Saint Louis From The River Below, 1832, George Catlin (1796-1892)

Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. [SAAM #1985.66.311.]

“Saint Louis … is a flourishing town, of 15,000 inhabitants, and destined to be the great emporium of the West … [It] is the great depot of all the Fur Trading Companies to the Upper Missouri and Rocky Mountains, and their starting-place; and also for the Santa Fe, and other Trading Companies, who reach the Mexican borders overland, to trade for silver bullion, from the extensive mines of that rich country …

I have also made it my starting-point, and place of deposit, to which I send from different quarters, my packages of paintings and Indian articles, minerals, fossils, &c.,

as I collect them in various regions, here to be stored till my return; and where on my last return, if I ever make it, I shall hustle them altogether, and remove them to the East.”

“Saint Louis … is a flourishing town, of 15,000 inhabitants, and destined to be the great emporium of the West … [It] is the great depot of all the Fur Trading Companies to the Upper Missouri and Rocky Mountains, and their starting-place; and also for the Santa Fe, and other Trading Companies, who reach the Mexican borders overland, to trade for silver bullion, from the extensive mines of that rich country … I have also made it my starting-point, and place of deposit, to which I send from different quarters, my packages of paintings and Indian articles, minerals, fossils, &c., as I collect them in various regions, here to be stored till my return; and where on my last return, if I ever make it, I shall hustle them altogether, and remove them to the East.”

- George Catlin, Letters and Notes, Volume 2, Number 35, 1841.

The steamboat in Catlin’s Saint Louis From The River Below was The Yellowstone, owned and operated by John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. During the 1830s, The Yellowstone was the most reliable form of transportation between Saint Louis and the fur trading centers and Native American villages in the upper Missouri Valley.

Dacota Woman and Assiniboin Girl, Karl Bodmer, 1844.

Aquatint, from an original Bodmer watercolor done in June of 1833.

Illustrated as Plate 9 in Travels in the Interior of North America

by Prince Maximilian, Koblenz, 1849.

Illustrated as Plate 9 in Travels in the Interior of North America by Prince Maximilian, Koblenz, 1849.

On April 19, 1833, in Saint Louis, Prince Maximilian, of Prussia, and the Swiss artist, Karl Bodmer, of Zurich, boarded The Yellowstone for their journey to Fort Pierre and Fort Union, nine hundred miles north of Saint Louis. On June 1, 1833, at Fort Pierre, now South Dakota, Bodmer painted a portrait of Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin, a Teton Sioux woman.

In the portrait, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin is wearing beaded moccasins, beaded leggings,

a leather dress, and a buffalo robe decorated with stylized human figures. At her neck and shoulders, the robe has been folded back against itself, creating a collar of brown buffalo fur. When Prince Maximilian offered to buy her dress, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin said no, but later agreed to sell him her buffalo robe.

In the portrait, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin is wearing beaded moccasins, beaded leggings, a leather dress, and a buffalo robe decorated with stylized human figures. At her neck and shoulders, the robe has been folded back against itself, creating a collar of brown buffalo fur. When Prince Maximilian offered to buy her dress, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin said no, but later agreed to sell him her buffalo robe.

Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin’s buffalo robe is in the collection of the Linden Museum, Stuttgart, Germany, by donation from Prince Maximilian. [LM #36102.]

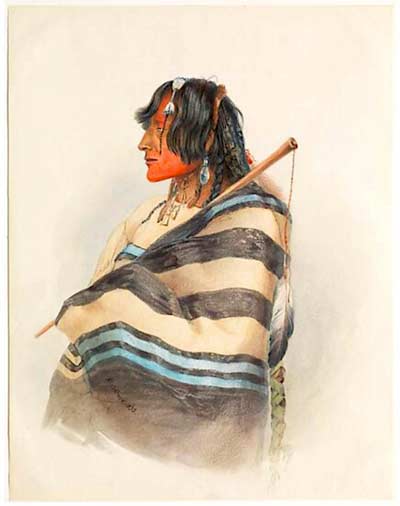

Kiasax (Bear-on-the-Left), 1833, by Karl Bodmer.

Watercolor on paper. The Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha.

Karl Bodmer met Kiasax in June of 1833, aboard the Assiniboine, a steamboat traveling north to Fort Union, on the Missouri River. In the watercolor, Kiasax is wearing a first phase chief’s blanket, Ute Style. Bodmer’s Kiasax is the earliest painting of a first phase by either an American or European artist.

Karl Bodmer met Kiasax in June of 1833, aboard the Assiniboine, a steamboat

traveling north to Fort Union, on the Missouri River. In the watercolor

Kiasax is wearing a first phase chief’s blanket, Ute Style. Bodmer’s Kiasax

is the earliest painting of a first phase by either an American or European artist.

Demand for the larger blankets with horizontal brown and white bands came from high-ranking members of the Arapahoe, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, Shoshoni, and Ute tribes. The term “chief’s blanket” came into use because the Spanish referred to high-ranking members of the Plains and Prairie tribes as “jefes.” In Spanish, “jefe” means “boss” or “leader.” Anglo-Americans referred to jefes as “chiefs.” While chief’s blankets were occasionally worn by members of the Navajo tribe, they never enjoyed the kind of popularity among the Navajo that they had among the chiefs of the Plains and Prairie tribes.

By 1830, the Navajo chief’s blanket had become a prestige garment and a valuable trade item throughout the Southwest, the Great Plains, the Prairie, and the Missouri Valley. The barter price for one chief’s blanket was fifty buffalo hides, twenty horses, ten rifles, or five ounces of gold. Chiefs of the Plains and Prairie tribes either wore chiefs blankets around their torsos, like buffalo robes, or gave them to their wives or daughters. During this period, most of the chief’s blankets woven by the Navajo and traded to Plains and Prairie chiefs were first phases.

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style,

Navajo, circa 1750-1800, also known as the Morris First Phase.

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1750-1800, also known as the Morris First Phase. The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

The Morris First Phase is illustrated as Plate 49 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund describe the first phase as “Navajo Shoulder Blanket (1750-1880), Banded,” and note that it was “Collected in 1937 by Earl H. Morris and Alfred V. Kidder from a Navajo grave in Canyon de Chelly.” “1750” is the earliest circa date assigned by Wheat and Hedlund to a Navajo chief’s blanket.

The Morris First Phase is also illustrated as Plate 63a in Amsden, Navaho Weaving, Its Technic and Its History, 1934. Amsden does not date the first phase, but suggests it could have been woven as early as “the year 1800.” The illustration in Amsden raises the question: If Morris and Kidder collected the first phase in 1937, how can it be illustrated in a book published in 1934? During the late 1920s and early1930s, Morris and Kidder worked together on reconstruction of the sandstone tower at Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto. They may have excavated the firstphase from a burial at Mummy Cave, prior to 1934.

The Morris First Phase is in the collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC), in Santa Fe, by donation from Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder. MIAC classifies the Morris First Phase as a grave good. The first phase is available for viewing only to Native Americans. [MIAC Catalog #9150/12.]

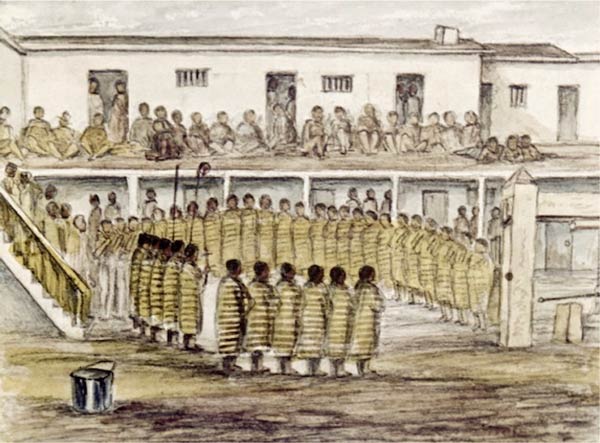

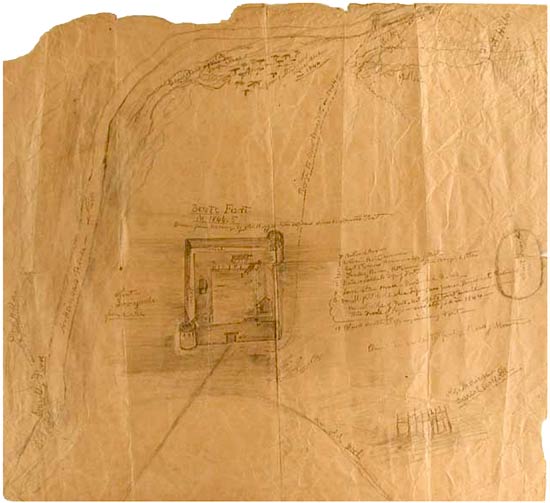

Cheyenne Scalp Dance at Bent’s Fort, Colorado, 1845.

Sketch by Lieutenant James W. Abert (1820-1897).

Lieutenant James W. Abert was a painter, explorer, and officer with the U. S. Army Topographical Engineers. In 1845, Abert was attached to the Third Expedition of Major John Charles Frémont. Frémont’s orders were to survey the Comanche and Kiowa regions along the Arkansas River and the Canadian River in what is now southeastern Colorado.

While Fremont’s Expedition was staying at Bent’s Fort, on the Arkansas River, Lieutenant Abert was invited to a Cheyenne Scalp Dance. At the dance, Abert saw forty Cheyenne women dancing in a circle. Each woman was wearing a first phase.

In his diary, Abert described the Cheyenne women and their blankets.“In the afternoon I was kindly invited by the gentlemen of the fort to see a scalp dance. On going up, I found about 40 women with faces painted red and black, nearly all cloaked with ‘Navahoe’ blankets and ornamented with necklaces and earrings, dancing to the sounds of their own voices and the four tambourines which were beat upon them by the men.” (Abert’s Diary, 1845.)

In 1844 and 1845,William M.Boggs worked at Bent’s Fort as a trader with the local tribes. Boggs was the son of Lilburn W. Boggs, the sixth governor of Missouri. In his Manuscript About Bent's Fort,William Boggs observes that the close weave and natural oil content of the wool in Navajo chief’s blankets made them valuable to the Cheyenne because “these qualities made them waterproof.”

A Map of Old Bents Fort drawn by William Boggs, circa 1850.

In the collection of the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.

In Boggs’s account of the same scalp dance at Bent’s Fort painted by Lieutenant Abert, Boggs describes the Navajo chief ’s blankets as “all alike, with white and black stripes[s] about two inches wide.” At the dance, Boggs watched “several hundred of these young Indian maidens, dressed in their Navajo blankets, form a circle at a war dance outside a circle of braves, who were dancing around a large bonfire with their trophies of Pawnee scalps.”

Lieutenant Abert’s and William Boggs’s accounts are quoted by Dr. Kathleen Whitaker in The Navajo Chief Blanket – A Trade Item Among Non-Navajo Groups, an article that appeared in the Winter, 1981, issue of American Indian Art Magazine.

For more about Lieutenant Abert, see Abert, Through The Country Of The Comanche Indians In The Fall Of The Year 1845, edited by John Galvin, 1970.

For more about William Boggs, see Boggs, The W. M. Boggs Manuscript about Bent’s Fort, Kit Carson, the Far West, and Life Among the Indians, 1905.

Upper Left: The Andy Williams Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1850

Upper Right: The Laramie Second Phase, Navajo, circa 1850

Lower Left: The Vroman Third Phase, Navajo, circa 1865

Lower Right: The Ernst Crosses Variant, Navajo, circa 1865

In Navajo culture, weaving a copy of a blanket you had already woven was taboo.

The taboo led to innovation. Innovation became a hallmark of classic Navajo weaving. Between 1830 and 1860, Navajo weavers added design elements to the bands and stripes of their chief’s blankets. Thin red stripes were an early innovation, followed

by horizontal rectangles and terraced diamonds.

After the Mexican-American War of 1848, U. S. Army expeditions began to arrive in the southwest. By 1860, most of the demand for Navajo chief’s blankets and Navajo serapes came from Anglo-American buyers. Anglo-American design preferences were not the same as Native American preferences. Native Americans preferred simplicity. Anglo-Americans preferred bold colors and complex patterns.

A Classic Chief’s Blanket Variant, Navajo, circa 1850,

also known as the SAR Variant.

A Classic Chief’s Blanket Variant, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the SAR Variant.

The SAR Variant measures 56 inches long by 71 inches wide, as woven.

As Anglo-Americans traders became familiar with Navajo chief ’s blankets, they categorized chief ’s blankets according to their designs. Chief ’s blankets with horizontal bands and stripes, but no designs, came to be known as “first phases.” Chief’s blankets with concentric squares or horizontal rectangles were called “second phases.” Chief ’s blankets with terraced diamonds were called “third phases.” Chief ’s blankets with combinations of horizontal rectangles, concentric squares, terraced diamonds, or other geometric designs were called “variants.”

While there were no words in Navajo for “first phase,” “second phase,” “third phase,” or “variant,” repetition of the terms by Anglo-American traders made them a part of the vocabulary used by nineteenth century merchants and tourists when they talked about Navajo chief’s blankets.

During the twentieth century, the numerical connotations of “first phase,” “second phase,” and “third phase” led Anglo-American collectors to assume that first phases were woven before second phases, and that second phases were woven before third phases and variants.While first phases were the earliest style of Navajo chief ’s blanket, examination of the designs, weaving techniques, and yarns in classic

(pre-1860) chief ’s blankets contradicts that assumption. Classic first phases, second phases, third phases, and variants were not woven in strict chronological order. Between 1830 and 1860, first phases, second phases, third phases, and variants were woven concurrently. Certain second phases, third phases, and variants were woven before certain first phases.

Native American thought sees events as taking place in cycles, where the beginning, middle, and end of a cycle can occur simultaneously. Anglo-American thought starts at the beginning of a narrative, proceeds chronologically through the narrative, and finishes at the end. The study of classic Navajo chief ’s blankets requires familiarity with both styles of thought.The two styles do not contradict each other so much as they inform each other and fill in each other’s gaps.

The Walentas Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

The first phase measures 57 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven.

The Walentas Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840. The first phase measures 57 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven. Sold by Sotheby’s, New York, for $522,500, on November 28, 1989. In the collection of David Walentas, New York.

Sold by Sotheby’s, New York, for $522,500, on November 28, 1989.

In the collection of David Walentas, New York.

Sold by Sotheby’s, New York, for $522,500, on November 28, 1989. In the collection of David Walentas, New York.

Why Are First Phases Valuable?

Classic first phases have been valuable trade items for two centuries. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the barter price for a first phase was fifty buffalo hides, twenty horses, ten rifles, or five ounces of gold. When a buyer pays a premium for

an item, regardless of whether that item is a classic car, a house, a first phase, or

a painting, they protect that item while they own it and they demand a premium

when they sell it.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Anglo-Americans replaced Native Americans as buyers for Navajo chief ’s blankets. Between 1860 and 1930, first phases were unpopular with Anglo-Americans, who thought they were too plain.

Between 1900 and 1930, the Fred Harvey Company in Albuquerque bought and sold many of the classic Navajo blankets now in museum and private collections. Harvey Company ledgers show that, between 1900 and 1930, classic third phases were the most expensive chief ’s blankets. First phases and second phases typically sold for half as much as third phases.The price structure reflected the Anglo-American preference for design complexity and aesthetic bias against simplicity.

The Deep, 1953, by Jackson Pollock (1912-1956).

Oil paint and enamel on canvas.

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Oil paint and enamel on canvas. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Between 1940 and 1960, abstract expressionism revolutionized the way the world looked at art. Before 1940, a painting had to “mean something.” When an artist created a painting, the painting had to represent a person, a place, or a thing. The depiction of that person, place, or thing could create and follow its own rules.

A painting could represent its subject as much through ambiguity as through realism, as long as it still had a subject.

In Europe and the United States, Pablo Picasso,Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Paul Gaugin were celebrated as great artists, and their best paintings were regarded as masterpieces. Through their innovative approaches to color, line, and perspective, Picasso, Van Gogh, Matisse, and Gaugin had altered the way the art world looked at paintings, but their paintings were still depictions of people, places, and things.

In the United States, between 1945 and 1960, the emergence of abstract expressionism changed what it meant to paint a painting. It also changed what it meant to look at a painting. Paintings by Richard Diebenkorn, Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin and Joan Mitchell were non-representational. Nothing was depicted.The subject of the painting was its lack of a subject. An abstract painting meant whatever the viewer wanted it to mean.

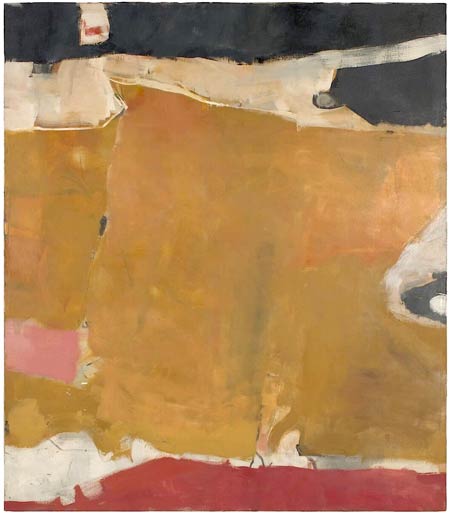

Untitled (Albuquerque), 1952, by Richard Diebenkorn.

Oil on canvas.

The Buck Collection at the UCI Institute

and Museum for California Art.

Untitled (Albuquerque), 1952, by Richard Diebenkorn. Oil on canvas. The Buck Collection at the UCI Institute and Museum for California Art.

The freedom to decide for yourself what a work of art “meant” turned you, the viewer, into the artist’s co-creator. The artist had applied paint to canvas in such a way that the meaning of the painting was no longer an issue.There was no right or wrong way to experience an abstract painting.You looked at the painting and drew your own conclusions. And, if your conclusions changed each time you looked at the painting, the freedom to change your mind about what the painting meant became the subject of the painting.

During the late 1960s, Tony Berlant, a contemporary artist in Santa Monica, started building a collection of Navajo blankets. In 1972, Berlant co-curated The Navajo Blanket, the first major museum exhibition of Navajo blankets. Mary Kahlenberg, Berlant’s co-curator, was the Textile Curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (L ACM A). The Navajo Blanket included chief’ s blankets, mantas, and serapes from Berlant’s collection.

After opening at LACMA, in 1972, The Navajo Blanket traveled to the Navajo Tribal Museum in Window Rock, Arizona; the Brooklyn Art Museum; the Institute for the Arts at Rice University, in Houston; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City; and the Kunstverein Museum in Hamburg, Germany.

Before The Navajo Blanket, American art collectors thought of Navajo blankets

as Indian relics. After The Navajo Blanket, many art collectors still thought of Navajo blankets as Indian relics, but a few collectors started looking at blankets from

a changed perspective. Some of those collectors were contemporary artists.

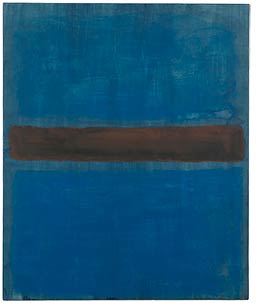

Left: Untitled, 1969, by Mark Rothko.

Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Right: The Berlant First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

During the 1970s,Tony Berlant became a prominent dealer in Navajo blankets. Jasper Johns, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol bought blankets from Berlant. By 1978, Christophe de Menil, an art collector in Houston, had started collecting blankets. de Menil was the daughter of Dominique and John de Menil, the co-founders of the Menil Collection, the Rothko Chapel, and the Cy Twombly Pavilion, in Houston.

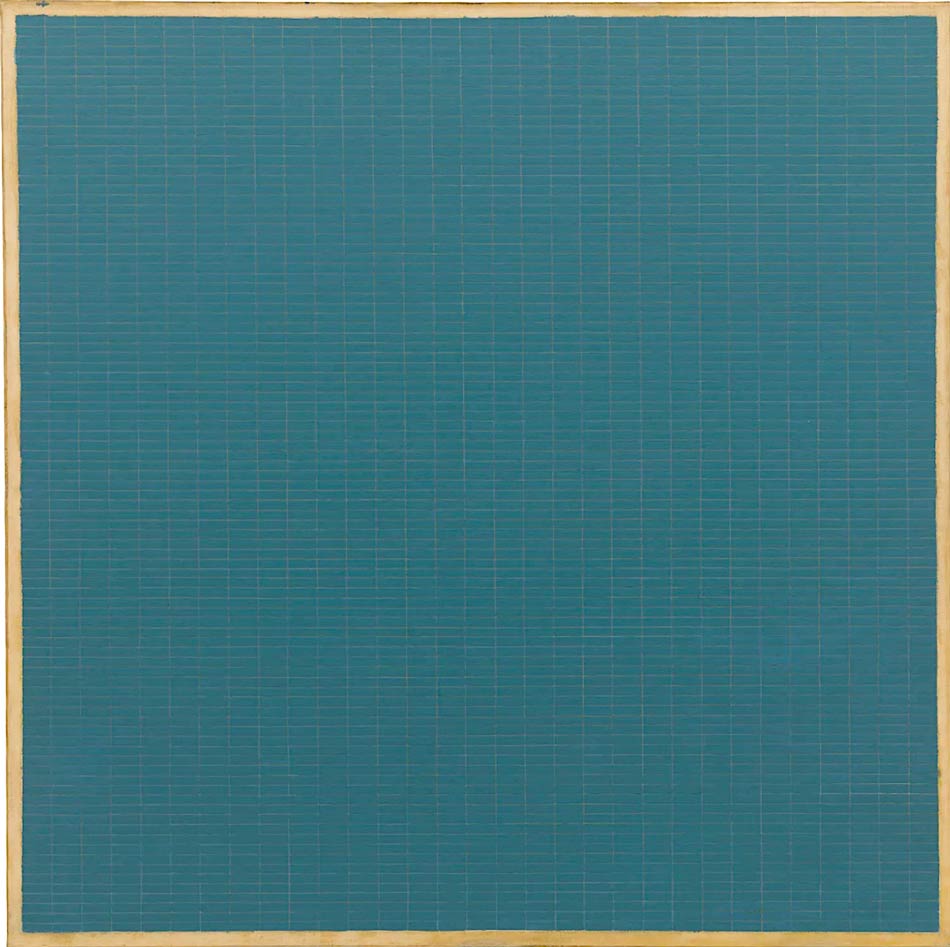

The popularity of Navajo blankets among contemporary artists and art collectors followed a pattern. If a Navajo blanket had visual aspects in common with an abstract expressionist painting, it had more value to a collector than a Navajo blanket that looked like an Indian relic. The less design a blanket had, the more appealing it became to collectors of contemporary art.

By the mid-1970s,the price structure for first phase chief’s blankets had reverted to the structure in place prior to 1860. First phases were selling for twice as much as second phases, third phases, or variants. On November 28, 1989, when Sotheby’s, New York, sold a Classic Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Walentas Bayeta First Phase, for $522,500, neither a second phase, a third phase, nor a variant had sold for more than $90,000, either at auction or through a private sale.

For the next twenty-three years, $522,500 stood as the auction record—both for

a first phase and for a Navajo blanket.

The Chantland Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

The first phase measures 58 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The Chantland Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840. The first phase measures 58 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The stains in the white bands were visible

in June, 2012, when the first phase sold for $1,800,000.

The stains in the white bands were visible in June, 2012, when the first phase sold for $1,800,000.

In February of 2012, Loren Krytzer, of Antelope Valley, California, consigned a classic bayeta first phase to John Moran Auctioneers in Altadena, California. The first phase had been acquired in 1870 by John Chantland, the owner of a general store in Mayville, North Dakota, and the Postmaster of Mayville. Chantland had accepted the first phase in trade for groceries. For the next 142 years, the first phase remained among Chantland’s descendants. Loren Krytzer is the great-great grandson of John Chantland.

On June 19, 2012, the Chantland Bayeta First Phase sold for $1,800,000. The buyer was the Donald Ellis Gallery, of New York.

In April, 2016, Ellis sold the first phase to Valerie and Charles Diker, of New York. Between 2018 and 2021, the first phase was on exhibit in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, by loan from the Dikers.

The sale of the Chantland Bayeta First Phase established the Navajo first phase as an object of beauty, rarity, and value. The art world took notice.

Between 2012 and 2022, contemporary art collectors started collecting classic

(pre-1865) first phases. Collector demand changed the art world’s perception of classic Navajo chief’s blankets. When contemporary art collectors looked at first phases, they saw many of the same abstract, understated qualities they appreciated in paintings by Agnes Martin, Richard Diebenkorn, Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, and other contemporary artists.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo circa 1800-1830. The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

Night Sea, 1963, by Agnes Martin.

Oil on Canvas. 72 inches long by 72 inches wide.

In the collection of SFMOMA, San Francisco.

Night Sea, 1963, by Agnes Martin. Oil on Canvas. 72 inches long by 72 inches wide. In the collection of SFMOMA, San Francisco.

A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1860,

also known as the Williams Bayeta First Phase.

A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1860, also known as the Williams Bayeta First Phase.

The first phase measures 67 inches wide by 53 inches long, as woven.

The first phase is ex- Billy Pearson, Healdsburg, California. During the late 1970s, the singer, Andy Williams, of Branson, Missouri, purchased the first phase from Pearson.

During the 1940s and 1950s, William A. “Billy” Pearson (1920-2002) was an American jockey in thoroughbred horse-racing, with eight hundred credited victories. In 1956 and 1957, after retiring from horse-racing, Pearson won $175,000 on the television quiz shows, The $64,000 Question and The $64,000 Challenge.

During the 1960s, Pearson became an art dealer in Los Angeles, New York, and Paris. While Pearson specialized in American folk art and Pre-Columbian art, he also bought and sold Navajo blankets. During the 1960s, Pearson became friends with the film director, John Houston, and with Andy Williams. During the 1970s, Pearson sold American folk art, paintings, and Navajo blankets to Williams.

In 1997 and 1998, the Saint Louis Art Museum held an exhibition entitled Navajo Weavings from the Andy Williams Collection. The Williams Bayeta First Phase was included, and is illustrated as Plate 6 in Hedlund, Navajo Weavings from the Andy Williams Collection, 1997, the exhibition catalog.

The center of the Williams Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1860.

In the Williams Bayeta First Phase, the red yarns are raveled bayeta dyed with

a combination of cochineal and lac. The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed with indigo. The brown and white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleeces.

The Williams Bayeta First Phase is not as finely woven as other classic first phases. Warps measure seven to the inch. Wefts measures twelve to the inch.

On September 12, 2012, Andy Williams died in Branson. On May 21, 2013, Williams’ collection of Navajo blankets was sold by Sotheby’s, New York. The Williams Bayeta First Phase sold for $221,000.

Given that the Chantland Bayeta First Phase had sold for $1,800,000, in June of 2012, many collectors and dealers had expected the Williams Bayeta First Phase to sell for a price that either approached or exceeded $1,800,000. When the Williams Bayeta First Phase sold for $1,579,000 less than the Chantland Bayeta First Phase, there was some confusion about why one classic bayeta first phase with impeccable collection history had set an auction record, while another classic bayeta first phase, from a celebrity owner’s collection, sold for so much less.

The difference in prices between the two bayeta first phase raises a critical issue about the values of classic first phases. When you bid at auction, you bid on a work or art, not on a category. When you pay for that work of art, you don’t pay for its catalog description. You buy the work of art.

The center of the Chantland Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

The difference between the Chantland Bayeta First Phase and the Williams Bayeta First Phase came down to their relative aesthetic merits. The Williams Bayeta First Phase photographed well, and it was a classic bayeta first phase, but in person it had

a dull, uneven surface. No matter how well it was displayed, light disappeared into

the first phase. When you were in the room with the Williams Bayeta First Phase, it looked like an Indian relic.

The Chantland Bayeta First Phase photographed well, too, but nothing in its pictures prepared you for the radiance it had in person. No matter how it was displayed, light came out of the first phase. When you were in the room with the Chantland Bayeta First Phase, its radiance was impossible to ignore.

In the Chantland First Phase, the red yarns are raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece. Lac dye, or kerria lacca, is

a fermented form of cochineal. Between 1800 and 1860, lac was imported by the British Empire from their colony in Bengal, India.

The Williams Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket. Navajo, circa 1860.

The first phase measures 67 inches wide by 53 inches long, as woven.

The Williams Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket. Navajo, circa 1860. The first phase measures 67 inches wide by 53 inches long, as woven.

The Chantland Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1840.

The first phase measures 68 inches wide by 58 inches long, as woven.

The Chantland Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1840. The first phase measures 68 inches wide by 58 inches long, as woven.