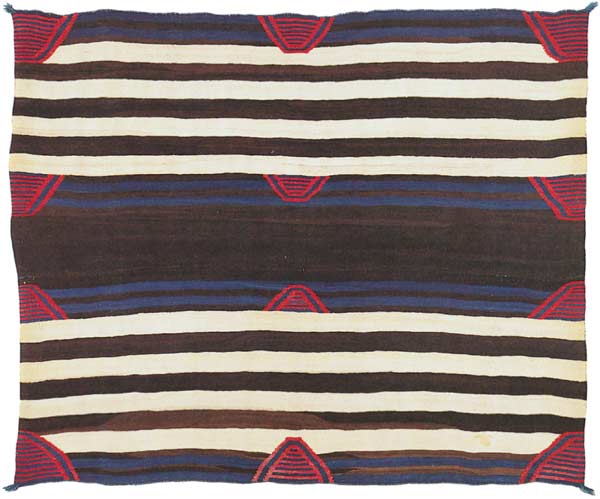

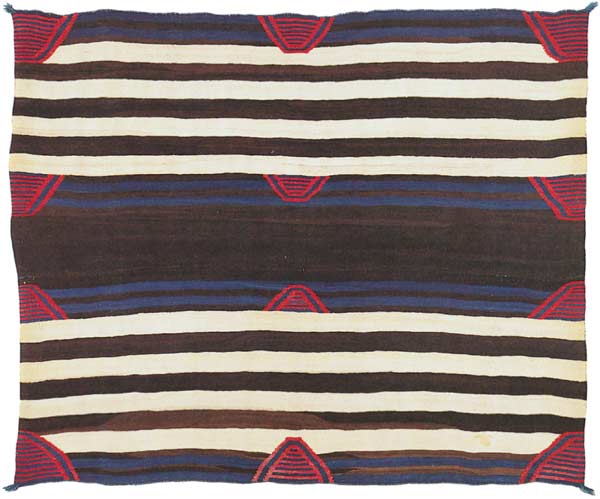

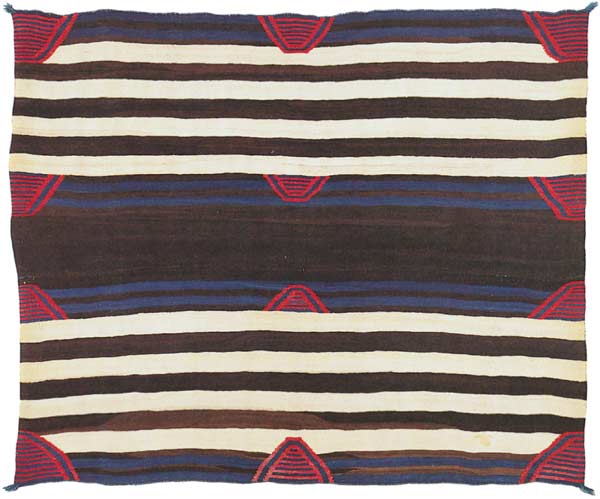

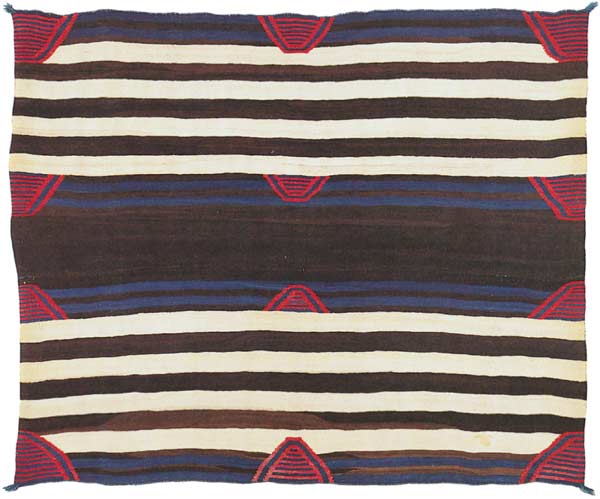

#6. An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1800-1830, also known as the Cahn First Phase. The Cahn First Phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven. Dimensions are small for a classic (pre-1865) first phase. The small dimensions support the 1800-1830 circa date.

The Cahn First Phase is the only known example of a classic first phase chief’s blanket, either Bayeta or Ute Style, with three brown bands and four white bands above and below its central panel. With the exception of the Schoch First Phase, all of the other known classic first phases have two brown bands and three white bands above and below their brown central panels. The Schoch First Phase has four brown bands and four white bands above and below its brown central panel.

The first phase’s thin, medium blue stripes, two additional brown stripes and two additional white stripes make it a unique example of the early classic first phase style. The absence of red stripes qualifies the Cahn First Phase as a Ute Style first phase.

The medium blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo circa 1800-1830. The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

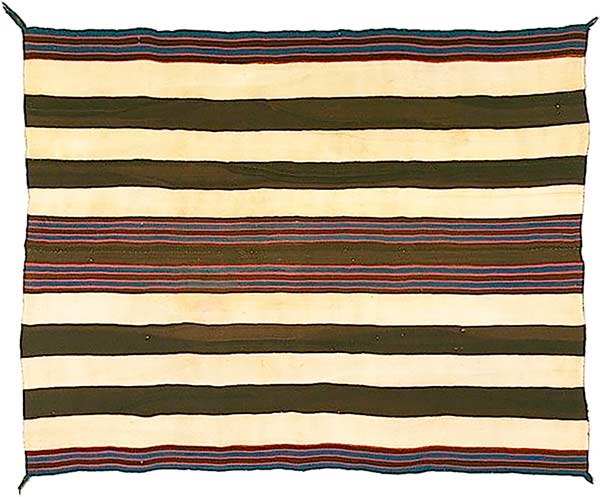

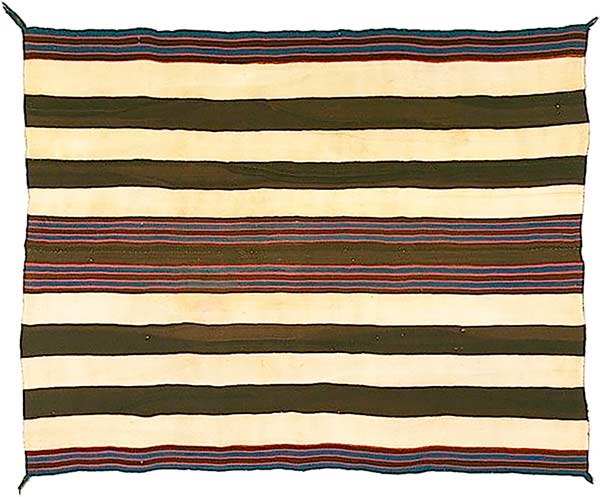

The Fred Harvey First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1850.

The first phase measures 51 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

The Fred Harvey First Phase has two brown bands and three white bands above and below its central panel. With the exceptions of the Cahn First Phase and the Schoch First Phase, all of the other classic Navajo first phase chief’s blankets in museum and private collections follow the Fred Harvey First Phase’s traditional format.

The Harvey First Phase is in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (NAMA), Kansas City, by purchase from the estate of Fred Harvey, in 1933. [NAMA Catalog #33-1430.]

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 51 inches long by 71 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase was collected by Lorenz Alphons Schoch in St. Louis,

in 1837. (In Swiss-German, Schoch is pronounced “shock.”) It is the earliest

Navajo blanket with documented collection history. The first phase is in

the collection of the Bernisches Historisches Museum in Bern, Switzerland.

[BHM Catalog #1890.410.0027.] It is the only classic (pre-1865) chief’s blanket

woven without blue yarns, and the only classic chief’s blanket with four brown

bands and four white bands above and below its brown central panel.

The Schoch First Phase was collected by Lorenz Alphons Schoch in St. Louis, in 1837. (In Swiss-German, Schoch is pronounced “shock.”) It is the earliest Navajo blanket with documented collection history. The first phase is in the collection of the Bernisches Historisches Museum in Bern, Switzerland. [BHM Catalog #1890.410.0027.] It is the only classic (pre-1865) chief’s blanket woven without blue yarns, and the only classic chief’s blanket with four brown bands and four white bands above and below its brown central panel.

The Cahn First Phase, Navajo circa 1800-1830.

The Cahn First Phase is Ex- Mark Winter, of Rinconada, New Mexico. Winter is

the owner of the Toadlena Trading Post in Toadlena, New Mexico. In 2003, Winter purchased the Cahn First Phase in Santa Fe, from an antiques dealer from Alabama. The antiques dealer told Winter he’d found the first phase being used as a tablecloth at a flea market near Mobile.

The Cahn First Phase is Ex- Mark Winter, of Rinconada, New Mexico. Winter is the owner of the Toadlena Trading Post in Toadlena, New Mexico. In 2003, Winter purchased the Cahn First Phase in Santa Fe, from an antiques dealer from Alabama. The antiques dealer told Winter he’d found the first phase being used as a tablecloth at a flea market near Mobile.

In 2004, Winter sold the first phase to Elissa and Paul Cahn, of Saint Louis. In 2004, the Cahns already owned a collection of Navajo blankets, Saltillo serapes, Rio Grande serapes, and Bolivian Aymara ponchos.

In 2013 and 2014, the Cahn First Phase was exhibited at the Saint Louis Art Museum with other Navajo blankets from the Cahns’ collection.

In 2016, the first phase was purchased from the Cahns by Joshua Baer & Company,

on behalf of the current owner.

In 2016, the first phase was purchased from the Cahns by Joshua Baer & Company, on behalf of the current owner.

In 2018, the Cahn First Phase was exhibited as part of Agnes Martin / Navajo Blankets, at Pace Gallery, Palo Alto, and at Pace / Chelsea, in New York.

Due to its radiant blue stripes and to its unusual pattern of three brown bands and four white bands above and below its central panel, the Cahn First Phase qualifies as

a candidate for both the earliest and finest known first phase in either a museum or private collection. While there are no other classic first phases with three brown bands and four white bands above and below their brown central panels, there are two other classic (pre-1865) chief’s blankets—one a classic third phase, the other a classic variant—with three brown bands and four white bands above and below their brown central panels.

Due to its radiant blue stripes and to its unusual pattern of three brown bands and four white bands above and below its central panel, the Cahn First Phase qualifies as a candidate for both the earliest and finest known first phase in either a museum or private collection. While there are no other classic first phases with three brown bands and four white bands above and below their brown central panels, there are two other classic (pre-1865) chief’s blankets—one a classic third phase, the other a classic variant—with three brown bands and four white bands above and below their brown central panels.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The SAR Variant, Navajo, circa 1850.

The SAR Variant is illustrated on the cover of Walk In Beauty. The variant

is in the collection of the School of Advanced Research (SAR), in Santa Fe.

The Twiss Third Phase, Navajo, circa 1855.

The Twiss Third Phase is in the collection of the National Museum

of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The SAR Variant, Navajo, circa 1850.

The SAR Variant is illustrated on the cover of Walk In Beauty. The variant is in the collection of the School of Advanced Research (SAR), in Santa Fe.

The Twiss Third Phase, Navajo, circa 1855.

The Twiss Third Phase is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC.

The SAR Variant, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the SAR Variant.

The SAR Variant measures 56 inches long by 71 inches wide, as woven.

The SAR Variant is illustrated on the cover of Walk In Beauty, 1977.

The variant is in the collection of the School of Advanced Research (SAR), in Santa Fe.

The SAR Variant, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the SAR Variant. The SAR Variant measures 56 inches long by 71 inches wide, as woven.

The SAR Variant is illustrated on the cover of Walk In Beauty, 1977. The variant is in the collection of the School of Advanced Research (SAR), in Santa Fe.

The SAR Variant is ex- Mrs. Sam Hamilton of Springer, New Mexico. Mrs. Hamilton may have originally purchased the variant from the author, Mary Austin. In 1942, the variant was purchased from Mrs. Hamilton by Amelia White of Santa Fe.

Amelia Elizabeth White (1878-1972), and her sister, Martha Root White, were the co-founders of the Indian Arts Fund in Santa Fe. Horace White (1834-1916), the sisters’ father, had been the editor of the New York Evening Post and the Chicago Tribune. In 1923, the White sisters were traveling to California, to view an eclipse, when they stopped in Santa Fe to get their hair done at the La Fonda Hotel. The sisters lived in Santa Fe for the rest of their lives.

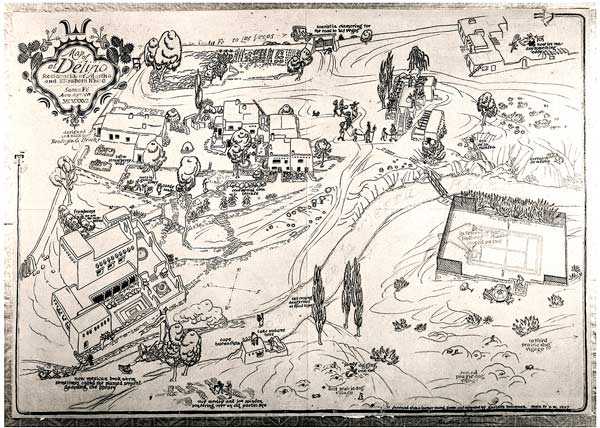

Between 1923 and 1930, the White sisters built El Delirio (“The Madness”), a large estate with multiple residences, public buildings, gardens, and stables on the east side of Santa Fe. Between 1925 and 1960, El Delirio was a mecca for anthropologists, archaeologists, artists, art collectors, musicians, Native Americans, Santa Feans, world travelers, and writers. In Santa Fe, the White sisters became famous for their costume parties at El Deliro, where their guests—including their Native American guests—were encouraged to come dressed in “native attire.”

An afternoon party at El Delirio in Santa Fe, 1926,

celebrating the installation of the pool on the estate. SAR Photo.

Amelia White, in 1929, at the International Exhibition, Seville, Spain, with pieces from her collection of Native American art. SAR photo.

Amelia White, dressed for the Fiesta Parade in Santa Fe, 1932. SAR photo.

The following account of the White sisters’ lives, and their relationship with Santa Fe, appears on sarweb.org, the website of the School of Advanced Research.

Amelia Elizabeth White (1878–1972) was born into an East Coast world of wealth and privilege. After serving as army nurses in Europe during World War I, she and her sister Martha chose to settle in the small town of Santa Fe, New Mexico. There Elizabeth became a passionate advocate for Pueblo Indian rights, an inspired patron and promoter of Indian art, and a dedicated community activist for the preservation of Santa Fe’s history. White organized several traveling expositions of Indian art and was instrumental in founding the Indian Arts Fund, the Laboratory of Anthropology, the Old Santa Fe Association, and the Santa Fe Indian Market. She also was a member of a wide circle of artists, writers, musicians, anthropologists, and archaeologists, whom she entertained lavishly at El Delirio (“The Madness”), the beautiful estate built by the White sisters in the 1920s. An eclectic combination of Moorish, Mexican, and Pueblo design, El Delirio was the setting for chamber music concerts, costume parties, and theatrical entertainments. Today it is the home of the School of American Research and the SAR Press.

A map of El Delirio, the White sisters’ estate in Santa Fe, 1927,

by Gustave Baumann.

The following account of how El Delirio became the home of the School of American Research, now the School of Advanced Research, in Santa Fe, appears on sarweb.org, the website of the School of Advanced Research.

In 1972 the School found a permanent home, a beautiful adobe estate on Santa Fe’s east side. “El Delirio” had been the home of Martha Root White and Amelia Elizabeth White, wealthy New York business women. Martha and Elizabeth built El Delirio in the 1920s, and it became a popular gathering place for Santa Fe artists, writers, and intellectuals—among them Edgar Hewett, Sylvanus Morley, and others closely associated with the School. The White sisters were avid patrons and promoters of Indian art, and together opened the first Native American art gallery in New York City. Elizabeth was a founding member of the Indian Arts Fund (IAF) in Santa Fe and sat on SAR’s Board of Managers for twenty-five years. Martha White died in 1937. When Elizabeth died at age 96 in 1972, she generously left El Delirio to the then-named School of American Research. In that same year, the IAF disbanded and deeded its superb collections of Southwest Indian art to SAR.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The SAR Variant, Navajo, circa 1850.

The variant measures 56 inches long by 71 inches wide, as woven.

The SAR Variant is one of two classic Navajo chief’s blankets that follow the Cahn First Phase’s atypical pattern of three brown bands and four white bands above and below their central panels. With the exception of the Twiss Third Phase, all of the other classic (pre-1865) chief’s blankets in museum and private collections follow the traditional pattern of two brown bands and three white bands above and below their brown central panels.

A Classic Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1855, also known

as the Twiss Third Phase. The absence of red stripes between the twelve design elements

qualifies the Twiss Third Phase as a Ute Style chief’s blanket.

A Classic Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1855, also known as the Twiss Third Phase. The absence of red stripes between the twelve design elements qualifies the Twiss Third Phase as a Ute Style chief’s blanket.

The third phase measures 57 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven.

Like the Cahn First Phase and the SAR Variant, the Twiss Third Phase has three brown bands and four white bands above and below its brown central panel.

The Twiss Third Phase was collected between 1855 and 1861 by Thomas S. Twiss (1807-1871), of Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory. Between 1855 and 1861, Twiss was the first Indian Agent at Fort Laramie. The Twiss Third Phase is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NMAI Catalog #10.8457.)

In 1996, the Twiss Third Phase was exhibited in Woven By The Grandmothers, at the National Museum of the American Indian, Bowling Green, New York. The third phase

is illustrated as Plate 13 in Bonar, Woven by the Grandmothers, the exhibition catalog, 1996. Bonar dates the third phase “1850-1860.”

In 1996, the Twiss Third Phase was exhibited in Woven By The Grandmothers, at the National Museum of the American Indian, Bowling Green, New York. The third phase is illustrated as Plate 13 in Bonar, Woven by the Grandmothers, the exhibition catalog, 1996. Bonar dates the third phase “1850-1860.”

The Twiss Third Phase is illustrated as Figure 36 in Berlant & Kahlenberg, Walk in Beauty, 1977. Berlant and Kahlenberg date the third phase “1850-1860.”

The Twiss Third Phase is illustrated as Plate 59 in Wheat & Hedlund, Blanket Weaving

in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund classify the third phase as “Phase III, early” and date it “1850-1860*.”

The Twiss Third Phase is illustrated as Plate 59 in Wheat & Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund classify the third phase as “Phase III, early” and date it “1850-1860*.”

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The Twiss Third Phase, Navajo, circa 1855.

The third phase measures 57 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven.

Interior of Fort Laramie, by Alfred Jacob Miller, circa 1858-1860.

Watercolor on paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

“This fort was built by Robert Campbell who named it

Fort William in honor of his friend and partner Wm. Sublette.

These gentlemen were the earliest pioneers after Messors

Lewis and Clarke, and had many battles with the Indians.”

“This fort was built by Robert Campbell who named it Fort William in honor of his friend and partner Wm. Sublette. These gentlemen were the earliest pioneers after Messors Lewis and Clarke, and had many battles with the Indians.”

From The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, by Alfred Jacob Miller (1810-1874).

The following history of Fort Laramie is adapted from Fort Laramie, a web page maintained by the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office.

In June of 1834, William Sublette and Robert Campbell established Fort William, the first fur trading post at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers. The confluence of the Laramie and the North Platte was one of the West’s most strategic locations, especially for the developing buffalo-robe trade that was replacing the beaver-fur trade that had been in place since the 1700s. Owned by the American Fur Company, Fort William’s location would soon control supply to a vast area of the central Rocky Mountains and a large area of the bison range in the Great Plains.

By 1849, the combination of the Gold Rush and the flood of westbound emigrants forced the United States government to insure the safety of westbound wagon trains. A string of Army posts along the Oregon Trail would provide a sense of security, keep the Trail open, and allow for reliable points of supply and repair. In April, 1849, after the U.S. Army purchased Fort William from the American Fur Company, for $4,000, the Regiment of Mounted Rifles moved into the fort, and re-named it Fort Laramie.

Fort Laramie became an oasis for travelers along the trails to Oregon, California and Utah. It was the only permanent trading post for the 800-mile span between Fort Kearney in what is now Nebraska, and Fort Bridger in what is now southwest Wyoming. In addition to the Oregon and California Trails, the Mormon Trail, Bozeman Trail, Pony Express Route, Transcontinental Telegraph Route, and the Deadwood and Cheyenne Stage Routes all passed through Fort Laramie.

Fort Laramie also served as a headquarters for the U. S. Army’s military campaigns. By 1852, more than fifty thousand pioneers had passed through the Fort. With each new wave of emigrants, tensions with Plains Indian groups increased. The Grattan Fight of 1854, which involved an incident with a wagon train near Fort Laramie, and the death of Lieutenant William Grattan, was the first major battle of the Indian Wars on the northern Great Plains.

In 1851, Plains Indian councils at Fort Laramie attempted to bring peace to the areas around the Fort. Treaties were signed, but subsequent U. S. Army campaigns against the Plains tribes testified to the Army’s failure to honor those treaties. Operating from Fort Laramie and neighboring posts, the Army subdued the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota, and other tribes in the area. In 1855, General William Harney’s expedition to punish the Sioux for killing Lieutenant William Grattan, in 1854, created a state of war. In September, 1855, the conflict culminated with the Army’s destruction of the Brulé Lakota village of Little Thunder at Ash Hollow, in western Nebraska Territory.

Exterior of Fort Laramie, by Alfred Jacob Miller, circa 1858-1860.

Watercolor on paper. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

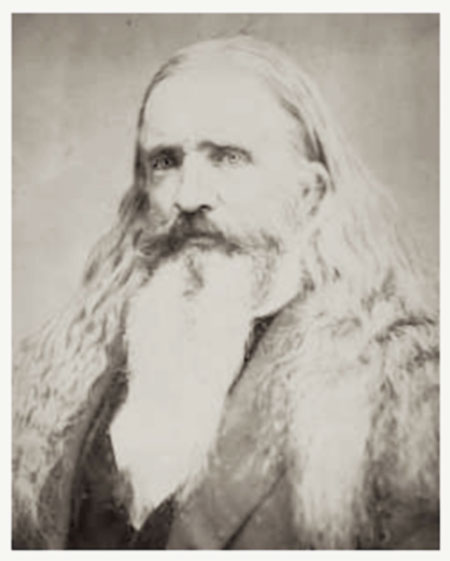

Thomas Sanders Twiss, the First Indian Agent at Fort Laramie, circa 1860.

The photograph is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, DC. [NMAI Catalog #N30123.]

On August 10, 1855, Thomas S. Twiss arrived at Fort Laramie, as the First Indian Agent at the Fort. On August 20, 1855, in his first letter to the Secretary of the Interior, Twiss wrote: “There is not, as I can find, within this agency, a single hostile Indian. On the contrary, all are friendly.”

Twiss identified several peaceful villages south of the South Platte and Laramie Rivers. He wrote that the villages desired to have a farmer and a blacksmith assigned to them. Twiss held a council with the chiefs of the Brulé Lakota and Oglala Lakota. By October, 1855, Twiss was convinced that neither the Brulé nor the Oglala had played any part in the conflicts during the past years.

During his first year at Fort Laramie, Twiss reached controversial opinions about the Fort’s military and civilian residents, including the traders and mountaineers. The mountaineers were former trappers and mountain men, some with Lakota wives and families. Twiss’s opinions brought him into conflict with Fort Laramie Commander William Hoffman, and with General William Selby Harney, who had led the attack on the Brulé Lakota at Ash Hollow.

Twiss opposed General Harney leading treaty negotiations—normally the job of the Indian Bureau. Harney ordered Twiss arrested and removed from office, but the general lacked authority over Twiss. The Secretary of Interior endorsed Twiss continuing in office and determining actions related to treaties and trade.

Twiss decided that traders at Fort Laramie, especially Seth Ward, were sources of corruption in the conduct of Indian affairs. He revoked Ward’s trading permit and established strict rules for trade with the tribes. Before long, traders at Fort Laramie stared making allegations about Twiss’s integrity and motives. In 1856, Twiss traveled east. That June, when Twiss checked into the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., criminal charges were filed against him. His accusers charged that Twiss had traded annuity goods to the Indians in exchange for buffalo hides. Annuity goods were the tribes’ annual payments from the government, as stated in the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Two interpreters from Fort Laramie testified that, in 1855, Twiss had exchanged cloth, blankets, knives, kettles, sugar, coffee and horses for a young Oglala woman.

In court, Twiss defended himself against the allegations. After hearing Twiss’s defense, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs cleared Twiss of all charges, which allowed Twiss to return to Fort Laramie. Despite accusations of impropriety, it’s clear that, in late 1855, Twiss had married Wanikiyewin, a member of the Spleen Band of the Oglala Lakota. Wanikiyewin, or “Savior of Her People,” was Chief Standing Elk’s daughter. She was also called Mary. Between 1855 and 1865, Wanikiyewin and Twiss had seven children together. In 1861, Twiss resigned his post as Indian Agent and left Fort Laramie, with Wanikiyewin.

After leaving Fort Laramie, Twiss and his family lived among the Oglala Lakota until his death in 1871. Today, the descendants of Wanikiyewin and Twiss are enrolled members of the Lakota Sioux Tribe on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

The seven children of Wanikiyewin and Thomas S. Twiss.

The photograph was taken the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, circa 1896.

The photograph was taken the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, circa 1896.

In 1996, the Twiss Third Phase was exhibited in Woven By The Grandmothers, an exhibition of Navajo blankets from the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). The exhibition took place at NMAI at Bowling Green, in New York City. The Twiss Third Phase is illustrated as Plate 13 in Bonar, Woven by the Grandmothers, the exhibition catalog, 1996. On Page 78 of Woven by the Grandmothers, under Notes On Selected Collectors, Bonar makes the following remarks about Thomas Twiss.

Thomas S. Twiss (b. New York 1802-71). From 1826 to 1828, Twiss was assistant professor of natural and experimental philosophy at West Point, his alma mater. He resigned from the army with the rank of major in 1929 and began teaching at South Carolina College. In 1847, he became superintendent of the Nesbitt Manufacturing Company’s Iron Works, and, in 1850, resident and consulting engineer for the Buffalo and New York Railroad. In 1855, he was appointed U. S. Indian agent for the Upper Platte, and in 1857 he moved the agency from Rawhide Butte Creek, east of Fort Laramie, to Deer Creek, on the Platte River. His district included Cheyennes, Arapahoes, Oglalas, and Brules, as well as visiting bands of Crows, Pawnee, and Ponca. Twiss was required to distribute blankets, food, and other goods provided by the government, but the Indians complained that frequently they did not receive their fair share… In 1861, when President Lincoln took office, Twiss was not reassigned to his post. In 1862, the Deer Creek agency was moved back to Fort Laramie. Twiss married an Oglala girl named Wanikiyewin, whom he called Mary, and today many of his descendants are enrolled Sioux members; most of them live on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

The Thomas S. Twiss Collection was presented to the museum by Harmon W. Hendricks, who purchased it in 1918 and 1919 from Daisy Barnett of New York. The collection includes two Navajo chief blankets (8.8038; 10.84457—Plate 13 accessioned in 1918 and 1921, and a small sarape diyogi (10.8456—plate 12) accessioned in 1921.

A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850,

also known as the Twiss First Phase.

The first phase measures 53 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the Twiss First Phase. The first phase measures 53 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

On Page 78 of Woven by the Grandmothers, under Notes On Selected Collectors, Bonar notes the following:

The Thomas S. Twiss Collection was presented to the museum by Harmon W. Hendricks, who purchased it in 1918 and 1919 from Daisy Barnett of New York. The collection includes two Navajo chief blankets (8.8038; 10.84457—Plate 13 accessioned in 1918 and 1921…

The Twiss Third Phase is NMAI #10.84457. The other chief’s blanket mentioned by Bonar is NMAI #8.8038—a Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the Twiss First Phase. The Twiss First Phase was not exhibited as part of Woven By The Grandmothers, and is not illustrated in the exhibition catalog.

The Twiss First Phase is illustrated as Plate 51 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest. Wheat and Hedlund date the first phase “1840-1850*,” and note

that it was “Collected about 1850 at Fort Laramie by Thomas S. Twiss (see Bonar 1996: 178).”

The Twiss First Phase is illustrated as Plate 51 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest. Wheat and Hedlund date the first phase “1840-1850*,” and note that it was “Collected about 1850 at Fort Laramie by Thomas S. Twiss (see Bonar 1996: 178).”

The Twiss First Phase is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. [NMAI #8.8038].

The Twiss Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850.

The first phase measures 53 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The Cahn First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 56 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven.

The presence of thin red stripes qualifies the Twiss First Phase as a bayeta first phase. The absence of thin red stripes qualifies the Cahn First Phase as a Ute Style first phase.

The Cahn First Phase, Navajo circa 1800-1830.

In person, a great Navajo blanket comes as a surprise. If you’ve seen the blanket before, the first thing you notice is how many of its qualities you either forgot or overlooked the first time you saw it. If you’ve seen a photograph of the blanket, but have not seen it in person, the first thing you notice when you see it in person is

its radiance. In the photograph, the blanket reflected light. In person, it radiates light. This happens regardless of whether you saw the photograph of the blanket in print or on a screen.

In person, a great Navajo blanket comes as a surprise. If you’ve seen the blanket before, the first thing you notice is how many of its qualities you either forgot or overlooked the first time you saw it. If you’ve seen a photograph of the blanket, but have not seen it in person, the first thing you notice when you see it in person is its radiance. In the photograph, the blanket reflected light. In person, it radiates light. This happens regardless of whether you saw the photograph of the blanket in print or on a screen.

If you’ve never seen the blanket before, either in person or in a photograph, the surprise is not so much the blanket’s beauty as its presence. Great Navajo blankets are living works of art. Being in a room with a great blanket is like being in a room with a charismatic person. No matter where you are in the room, if the charismatic person is in the room with you, you feel her or his presence. Beauty approaches you through your eyes. When you see beauty, it works its way through your mind and

your body, but the process starts with your eyes.

If you’ve never seen the blanket before, either in person or in a photograph, the surprise is not so much the blanket’s beauty as its presence. Great Navajo blankets are living works of art. Being in a room with a great blanket is like being in a room with a charismatic person. No matter where you are in the room, if the charismatic person is in the room with you, you feel her or his presence. Beauty approaches you through your eyes. When you see beauty, it works its way through your mind and your body, but the process starts with your eyes.

Presence is different. When you’re in the presence of presence, there’s no escape. Presence approaches you through all five of your senses, and probably through your sixth and seventh senses. In the same way that beauty and love are connected, presence is connected to power. When you experience the presence of a great person, a great landscape, or a great work of art, you experience power.

When people ask me if I have a favorite Navajo blanket, I tell them I have at least ten, but that it would be sophistry to single out one blanket and say I love it more than the other nine. Each time I give someone that answer, I remember the Cahn First Phase and wonder whether or not I told the truth.