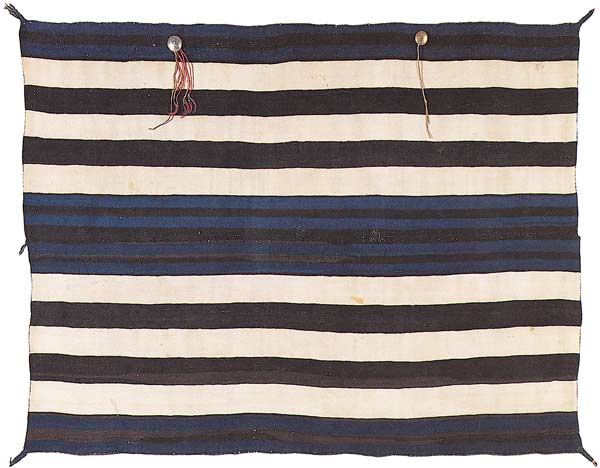

#9. A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase. The first phase measures 51 inches long inches

by 71 inches wide, as woven.

#9. A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase. The first phase measures 51 inches long inches by 71 inches wide, as woven.

The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase is the earliest bayeta first phase with documented collection history. The first phase was collected in 1851, at Zuni Pueblo, by Samuel Woodhouse, an American ornithologist and surgeon. Woodhouse acquired the first phase in mint condition. The first phase is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC., and is on display at the Museum. [NMAI #11.8280].

The first phase’s red stripes qualify it as a bayeta first phase. There are less than eighty classic (pre-1865) first phases woven in the man’s style in museum and private collections. Less than sixty-five are Ute Style. Less than fifteen are bayeta first phases.

Above: The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1850.

The first phase measures 51 inches long inches by 71 inches wide, as woven.

Below: The De Cost Smith First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1850.

The first phase measures 55 inches long by 72 inches wide, as woven.

The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase’s thin stripes of raveled red bayeta qualify it as

a bayeta first phase. Bayeta first phases have thin red stripes, thicker blue stripes, and alternating brown and white bands above and below their central panels.

The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase’s thin stripes of raveled red bayeta qualify it as a bayeta first phase. Bayeta first phases have thin red stripes, thicker blue stripes, and alternating brown and white bands above and below their central panels.

The De Cost Smith First Phase’s lack of red stripes qualifies it as a Ute Style first phase. Ute Style first phases have blue stripes and alternating brown and white bands above and below their central panels, but no red stripes.

Classic Ute Style first phases were woven between 1800 and 1850. Classic bayeta

first phases were woven between 1840 and 1865. While the Ute Style first phase is the earlier form, it would be a mistake to assume that every Ute Style first phase was woven before every bayeta first phase.

Raveled bayeta was available to Navajo weavers throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. We know this because of the approximately fifty classic bayeta poncho serapes woven between 1825 and 1850 that are now in museum and private collections.

Classic Ute Style first phases were woven between 1800 and 1850. Classic bayeta first phases were woven between 1840 and 1865. While the Ute Style first phase is the earlier form, it would be a mistake to assume that every Ute Style first phase was woven before every bayeta first phase.

Raveled bayeta was available to Navajo weavers throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. We know this because of the approximately fifty classic bayeta poncho serapes woven between 1825 and 1850 that are now in museum and private collections.

In Navajo culture, weaving a copy of a blanket you had already woven was taboo.

The taboo led to innovation. Innovation became a hallmark of classic Navajo weaving. Between 1830 and 1860, Navajo weavers added design elements to the bands and stripes of their chief’s blankets. Red stripes were an early innovation, followed by horizontal rectangles and terraced diamonds.

In Navajo culture, weaving a copy of a blanket you had already woven was taboo. The taboo led to innovation. Innovation became a hallmark of classic Navajo weaving. Between 1830 and 1860, Navajo weavers added design elements to the bands and stripes of their chief’s blankets. Red stripes were an early innovation, followed by horizontal rectangles and terraced diamonds.

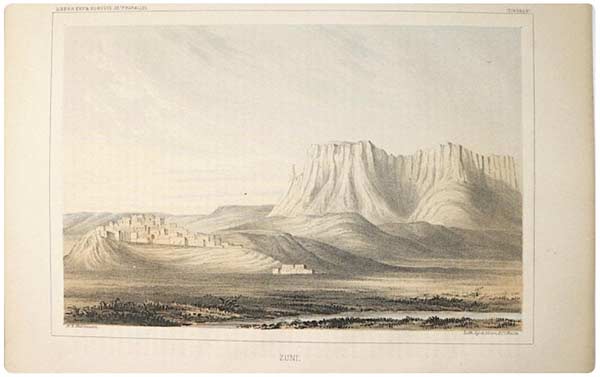

Zuni, 1856. United States Pacific Railroad Survey.

From an original 1853 drawing by H. B. Möllhausen (1825-1905), of Prussia.

Zuni Pueblo is known to the Zuni people as Halona Idiwan’a, or “the Middle Place.” The Zuni people refer to themselves as A’shiwi. The literal translation of A’shiwi is

“the flesh.” To the Zuni people, A’shiwi means “the flesh people.”

Zuni Pueblo is known to the Zuni people as Halona Idiwan’a, or “the Middle Place.” The Zuni people refer to themselves as A’shiwi. The literal translation of A’shiwi is “the flesh.” To the Zuni people, A’shiwi means “the flesh people.”

Prior to 1540, and the arrival of the Spanish, Zuni Pueblo was a trading center for pre-contact Native Americans. Between 1540 and 1821, Zuni Pueblo became an important northern crossroads in what was then New Spain.

The Mexican War of Independence occurred between 1810 and 1821. In 1821, the Republic of Mexico declared independence from Spain. Between 1821 and the end

of the Mexican-American war of 1848, Zuni Pueblo became commercial center for Apaches, Acomas, Hopis, Mexicans, Navajos, and to a lesser extent, Anglo-Americans.

The Mexican War of Independence occurred between 1810 and 1821. In 1821, the Republic of Mexico declared independence from Spain. Between 1821 and the end of the Mexican-American war of 1848, Zuni Pueblo became commercial center for Apaches, Acomas, Hopis, Mexicans, Navajos, and to a lesser extent, Anglo-Americans.

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and the end Mexican-American War of 1848, sovereignty over California, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming passed from Mexico

to the United Sates. The areas ceded by Mexico amounted to more than fifty

percent of Mexico’s pre-1848 territory. After 1848, Zuni Pueblo became part

of the United States.

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and the end Mexican-American War of 1848, sovereignty over California, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming passed from Mexico to the United Sates. The areas ceded by Mexico amounted to more than fifty percent of Mexico’s pre-1848 territory. After 1848, Zuni Pueblo became part of the United States.

Zuni Pueblo’s location along the Zuni River—a tributary of the Little Colorado River—made it a natural stopping point for travelers from Chaco Canyon and the Ute Tribe to the north; from Santa Fe, the Rio Grande Valley, and Acoma Pueblo to the east; from Casas Grandes and Mexico to the south; and from the Hopi villages and the Mohave settlements to the west. The Navajo were active traders at Zuni Pueblo. Navajo women wove and sold their blankets at the pueblo.

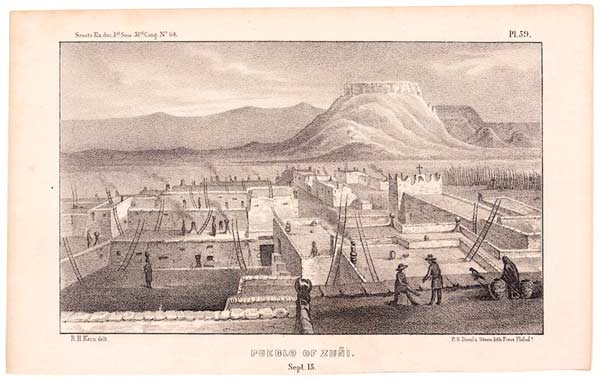

Pueblo of Zuñi, 1850, by P. S. Duval, lithographer, of Philadelphia.

From an original 1849 drawing by Richard H. Kern (1821-1853), of Philadelphia.

Prior to 1848, existing maps of the territories west of the Rio Grande Valley were drawn either by French or Spanish cartographers. In 1851, US Army Brevet Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves (1810-1888) led an expedition down the Zuni River, the Little Colorado River, and the Colorado River. John G. Parke was Sitgreaves’s second-in command. Antoine Leroux was the expedition’s guide. Samuel W. Woodhouse,

a surgeon and ornithologist from Philadelphia, and a friend of Captain Sitgreaves,

was the expedition’s medic.

Prior to 1848, existing maps of the territories west of the Rio Grande Valley were drawn either by French or Spanish cartographers. In 1851, US Army Brevet Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves (1810-1888) led an expedition down the Zuni River, the Little Colorado River, and the Colorado River. John G. Parke was Sitgreaves’s second-in command. Antoine Leroux was the expedition’s guide. Samuel W. Woodhouse, a surgeon and ornithologist from Philadelphia, and a friend of Captain Sitgreaves, was the expedition’s medic.

The Sitgreaves Expedition was the first systematic survey of the area of the upper region of New Mexico Territory between Zuñi Pueblo and the Colorado River. Sitgreaves’ mission was to find a reliable route to California, and to produce maps

of the territories west of the Rio Grande, with details, distances, and elevations in English.

The Sitgreaves Expedition was the first systematic survey of the area of the upper region of New Mexico Territory between Zuñi Pueblo and the Colorado River. Sitgreaves’ mission was to find a reliable route to California, and to produce maps of the territories west of the Rio Grande, with details, distances, and elevations in English.

The expedition of ten officers and thirty infantryman left Santa Fe on August 15, 1851, and reached Zuni Pueblo on September 1, 1851. The expedition remained at Zuni Pueblo until September 24, 1851, when it continued west to Yuma, Arizona, the Colorado River, and the Sea of Cortez.

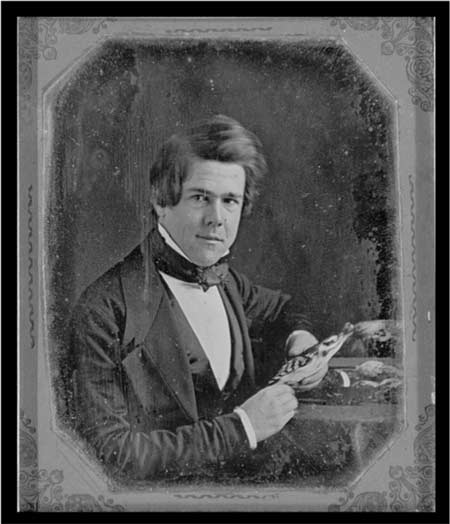

Above: Samuel Washington Woodhouse (1821-1904).

Woodhouse is holding a stuffed bird specimen. Daguerreotype, 1847.

Photographer unknown. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Below: Samuel Washington Woodhouse, 1857, by Edward Bowers.

The Woodhouse Second Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1840.

The second phase measures 56 inches long 75 inches wide by, as woven.

Condition is excellent with no restoration. Corner tassels, side selvages

and top and bottom edge cords are original and intact.

Condition is excellent with no restoration. Corner tassels, side selvages and top and bottom edge cords are original and intact.

The Woodhouse Second Phase was one of two classic (pre-1865) chief’s blankets collected in 1851 by Samuel W. Woodhouse (1821-1904), the surgeon and ornithologist who accompanied Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves of the United States Topographical Engineer Corps on the Sitgreaves Expedition. The other chief’s blanket was the Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase. Both chief’s blankets were collected in mint condition.

In 1996, the Woodhouse Second Phase was exhibited as part of Woven by the Grandmothers, at the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, at Bowling Green, New York, 1996. The Woodhouse Second Phase is illustrated as Plate 15 in Bonar, Woven by the Grandmothers, 1996. Bonar dates the second phase “1840-1850” and classifies its red yarns as “raveled yarns, 3z, lac, crimson, lac and cochineal crimson…”

The second phase is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. It is the earliest second phase with

a documented collection history.

The second phase is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. It is the earliest second phase with a documented collection history.

In the Woodhouse Second Phase, one of the red yarns is raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. The other red yarn is raveled bayeta piece-dyed with a combination of cochineal and lac. Both raveled red yarns display their original raised nap, an indication that the second phase saw little or no use as a garment after being acquired from

its weaver. The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo.

Both the brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

In the Woodhouse Second Phase, one of the red yarns is raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. The other red yarn is raveled bayeta piece-dyed with a combination of cochineal and lac. Both raveled red yarns display their original raised nap, an indication that the second phase saw little or no use as a garment after being acquired from its weaver. The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. Both the brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

Above: The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1850.

The first phase measures 71 inches wide by 51 inches long, as woven.

Below: The Woodhouse Second Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1850.

The second phase measures 56 inches long 75 inches wide by, as woven.

In 1996, the Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase and the Woodhouse Second Phase were both exhibited as part of Woven by the Grandmothers, an exhibition of classic and

late classic Navajo blankets from the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Woven By The Grandmothers appeared at NMAI, Bowling Green, in New York.

In 1996, the Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase and the Woodhouse Second Phase were both exhibited as part of Woven by the Grandmothers, an exhibition of classic and late classic Navajo blankets from the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Woven By The Grandmothers appeared at NMAI, Bowling Green, in New York.

The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase is illustrated as Plate 14 in Bonar, Woven By The Grandmothers, 1996—the exhibition catalog. Bonar dates the first phase “1840-1850.”

The Woodhouse Second Phase is Illustrated as Plate 15 in Bonar, Woven by the Grandmothers. Bonar dates the second phase “1840-1850.” Both chief’s blankets are in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

On Page 178 of Woven by the Grandmothers, Bonar makes the following observations regarding Samuel Woodhouse and the two Woodhouse chief’s blankets.

Samuel Washington Woodhouse (1821-1904)

Woodhouse, a Philadelphia physician and an avid ornithologist, was appointed surgeon and naturalist of two expeditions in 1849 and 1850

to survey the Creek Cherokee boundary in Indian Territory. In 1851, he participated in a reconnaissance of southwest territory under the command of Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, again as surgeon-naturalist. The region had recently been acquired by the United States from Mexico and was little known. As Sitgreaves wrote in his 1853 Report of an Expedition Down the Zuni

and Colorado Rivers, his instructions were to explore the Zuni River to its junction with the Colorado River, “determining its course and character, particularly in reference to its navigable properties, and to the character of its adjacent land and productions,” and then to follow the Colorado to its junction with the Gulf of California. The party marched from Santa Fe on 15 August and reached Zuni on 1 September, where it was detained until 24 September.

Woodhouse, a Philadelphia physician and an avid ornithologist, was appointed surgeon and naturalist of two expeditions in 1849 and 1850 to survey the Creek Cherokee boundary in Indian Territory. In 1851, he participated in a reconnaissance of southwest territory under the command of Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, again as surgeon-naturalist. The region had recently been acquired by the United States from Mexico and was little known. As Sitgreaves wrote in his 1853 Report of an Expedition Down the Zuni and Colorado Rivers, his instructions were to explore the Zuni River to its junction with the Colorado River, “determining its course and character, particularly in reference to its navigable properties, and to the character of its adjacent land and productions,” and then to follow the Colorado to its junction with the Gulf of California. The party marched from Santa Fe on 15 August and reached Zuni on 1 September, where it was detained until 24 September.

Appended to Sitgreaves report is one by Woodhouse in which he describes the plants and animals he observed on his travels, making special note of previously unrecorded species. Woodhouse was probably at Zuni when he collected two chief’s blankets (11.8280 - plate 14; 11.8281 – plate 15). The museum purchased the blankets from S. W. Woodhouse, Jr., and they were accessioned in 1923.

Samuel Washington Woodhouse, 1857.

From the Woodhouse Album of CDVs, Philadelphia.

In 1923, both of the Woodhouse chief’s blankets were purchased from S. W. Woodhouse, Jr., Samuel Woodhouse’s son, by the Museum of the American Indian / Heye Foundation, New York. In 1989, the collection of the Museum of the American Indian was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC, and

became what is now the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution.

In 1923, both of the Woodhouse chief’s blankets were purchased from S. W. Woodhouse, Jr., Samuel Woodhouse’s son, by the Museum of the American Indian / Heye Foundation, New York. In 1989, the collection of the Museum of the American Indian was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC, and became what is now the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution.

The Woodhouse chief’s blankets show no signs of having been woven by the same weaver. Both were collected by Woodhouse in mint condition. Neither the first phase nor the second phase shows evidence of having been worn as a garment. Corner tassels, side selvages and top and bottom edge cords on both chief’s blankets are original. The raveled bayeta in each chief’s blanket retains its original raised nap. The original condition of both chief’s blankets supports the theory that Woodhouse purchased each chief’s blanket off the loom from the Navajo woman who wove it.

The Woodhouse Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850.

The first phase measures 71 inches wide by 51 inches long, as woven.

Condition is excellent with no restoration. Braided corner tassels,

side selvages, and top and bottom edge cords are original and intact.

Condition is excellent with no restoration. Braided corner tassels, side selvages, and top and bottom edge cords are original and intact.

The red yarns are raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. The red yarns retain their original raised nap, an indication that the first phase saw little or no use as a garment after being acquired from its weaver. The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

In person, the Woodhouse First Phase’s white yarns appear as a deep ivory. Its blue yarns radiate light. Its brown handspun yarns are more variegated than they appear

in photographs. Its red yarns are a deeper, more saturated red than the raveled red bayeta you usually see in classic bayeta first phases. The overall visual effect of the Woodhouse First Phase is powerful. At the National Museum of the American Indian, where the first phase is on display, there’s usually one group of people standing in front of the first phase and a second group behind the first group, waiting to get

a closer look.

In person, the Woodhouse First Phase’s white yarns appear as a deep ivory. Its blue yarns radiate light. Its brown handspun yarns are more variegated than they appear in photographs. Its red yarns are a deeper, more saturated red than the raveled red bayeta you usually see in classic bayeta first phases. The overall visual effect of the Woodhouse First Phase is powerful. At the National Museum of the American Indian, where the first phase is on display, there’s usually one group of people standing in front of the first phase and a second group behind the first group, waiting to get a closer look.