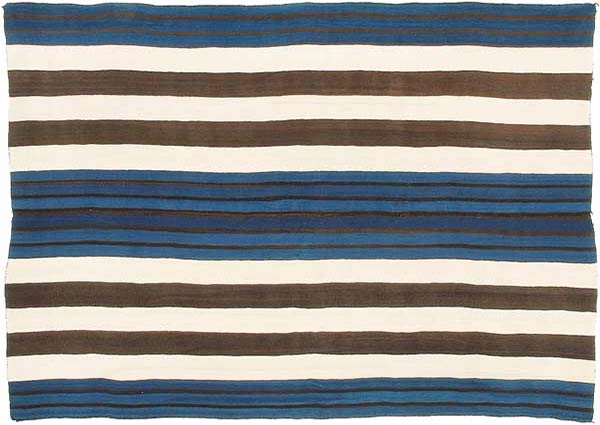

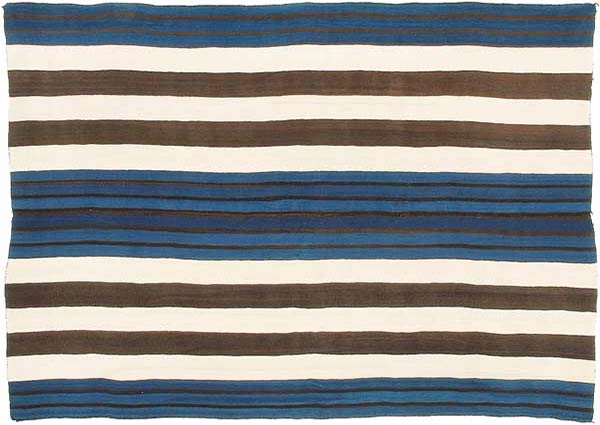

#7. A Late Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870,

also known as the Pytka First Phase. The first phase’s four blue bands, and its three panels of alternating brown and white stripes, are both unique to the first phase. The Pytka First Phase qualifies as a candidate for the finest known late classic first phase in either a museum or private collection.

#7. A Late Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870, also known as the Pytka First Phase. The first phase’s four blue bands, and its three panels of alternating brown and white stripes, are both unique to the first phase. The Pytka First Phase qualifies as a candidate for the finest known late classic first phase in either a museum or private collection.

The Pytka First Phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven. Its square dimensions are also unique. All of the other classic and late classic Navajo chief’s blankets were woven as horizontal rectangles. 99% of the classic and late classic chief’s blankets woven in the woman’s style measure approximately 45 inches long by

55 inches wide, as woven.

The Pytka First Phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven. Its square dimensions are also unique. All of the other classic and late classic Navajo chief’s blankets were woven as horizontal rectangles. 99% of the classic and late classic chief’s blankets woven in the woman’s style measure approximately 45 inches long by 55 inches wide, as woven.

The first phase is ex- Joe Pytka, Los Angeles.

This is an across-the-room first phase. When you first see it, its atmospheric blue bands appear as background and its three panels of alternating brown and white stripes appear as foreground. Then they switch. The inversion is not so much optical

as it is rhythmic. No matter how much time you spend with this first phase, it always shows you something new, something you didn’t expect from its simple arrangement of horizontal bands and stripes.

This is an across-the-room first phase. When you first see it, its atmospheric blue bands appear as background and its three panels of alternating brown and white stripes appear as foreground. Then they switch. The inversion is not so much optical as it is rhythmic. No matter how much time you spend with this first phase, it always shows you something new, something you didn’t expect from its simple arrangement of horizontal bands and stripes.

Above: The Pytka First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870. The first phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven. The first phase’s square dimensions, four blue panels, and three separate panels of alternating brown and

white stripes are each unique to the first phase.

Below: A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860, also known as the Taylor First Phase. The Taylor First Phase measures 45 inches long by

57 inches wide, as woven. The horizontal rectangle is the traditional format for classic and late classic Navajo chief’s blankets, in all phases, in both the man’s and the woman’s style. The Taylor First Phase also follows the traditional woman’s style format of two panels of alternating brown and gray stripes—one above, the other below, its central panel.

Above: The Pytka First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870. The first phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven. The first phase’s square dimensions, four blue panels, and three separate panels of alternating brown and white stripes are each unique to the first phase.

Below: A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860, also known as the Taylor First Phase. The Taylor First Phase measures 45 inches long by 57 inches wide, as woven. The horizontal rectangle is the traditional format for classic and late classic Navajo chief’s blankets, in all phases, in both the man’s and the woman’s style. The Taylor First Phase also follows the traditional woman’s style format of two panels of alternating brown and gray stripes—one above, the other below, its central panel.

Joe Pytka and Michael Jackson, on the set of Beat It, 1983.

Joe Pytka was born in Pittsburgh, in 1938. Between 1980 and 2020, Pytka had

a legendary career as a director of American films, music videos, and television commercials. Over the course of his career, Pytka directed commercials, films, and videos for Michael Jackson, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, Britney Spears, Shaquille O’Neil, and Tiger Woods, including the Nike commercial, I Am Tiger Woods.

Joe Pytka was born in Pittsburgh, in 1938. Between 1980 and 2020, Pytka had a legendary career as a director of American films, music videos, and television commercials. Over the course of his career, Pytka directed commercials, films, and videos for Michael Jackson, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, Britney Spears, Shaquille O’Neil, and Tiger Woods, including the Nike commercial, I Am Tiger Woods.

Pytka directed more than eighty Super Bowl commercials. He won the USA Today Super Bowl Ad Meter Poll seven times. Security Camera, one of Pytka’s Super Bowl commercials for Pepsi, was chosen as the best commercial in the history of the poll. Hare Jordan, a Pytka commercial for Nike, was developed into the film Space Jam, also directed by Pytka.

In 1987, in cooperation with the Partnership for a Drug Free America, Pytka directed the original version of This Is Your Brain On Drugs.

Joe Pytka has over fifty pieces of his work in the permanent collection of the

Museum of Modern Art in New York. He lives in Los Angeles.

Joe Pytka has over fifty pieces of his work in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He lives in Los Angeles.

Classic Navajo blankets on display in one of Joe Pytka’s

guest houses at Las Milpas in Santa Fe, 2017.

Classic Navajo blankets on display in one of Joe Pytka’s guest houses at Las Milpas in Santa Fe, 2017.

A Navajo double saddle blanket in the bedroom

at one of the guest houses at Las Milpas.

A Navajo double saddle blanket in the bedroom at one of the guest houses at Las Milpas.

In 1990, Pytka bought Las Milpas, a large estate in the historic district on the east side of Santa Fe. For the next ten years, Pytka worked with Ward Allen Minge, a New Mexico architectural historian, on the restoration of the main house, guest houses, and gardens at Las Milpas. During the 1990s, Pytka acquired a collection of Navajo blankets, Navajo rugs, and Rio Grande serapes. Pytka displayed his collection in the main house and guest houses at Las Milpas.

In 1997, Joe Pytka purchased the Pytka First Phase from Joshua Baer & Company.

In 2015, Joshua Baer & Company repurchased the first phase from Pytka. Later in 2015, the Pytka First Phase was purchased by its current owner, from Joshua Baer & Company. The first phase has been in the current owner’s collection since 2015.

Condition of the Pytka First Phase is excellent with less than 1% restoration. Corner tassels, side selvages, and top and bottom edge cords are 99% original. Less than 1%

of the classic and late classic first phases in museum and private collections survived in comparable condition. The first phase shows no signs of wear. It was probably collected by its original owner from the Navajo woman who wove it.

The blue yarns are handspun Merino fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The black and charcoal gray yarns are handspun Merino fleece dyed in their yarns with synthetic dyes. The dark brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Merino fleece.

The Pytka First Phase contains a large amount of medium blue handspun yarns.

The only other Navajo first phase with a comparable amount of medium blue handspun yarns is a Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket with Twelve Blue Bands, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Peterson First Phase. The Peterson First Phase is on exhibit at the Scottsdale Museum of the West, by loan from Tim Peterson, of Boston and Scottsdale.

In 1997, Joe Pytka purchased the Pytka First Phase from Joshua Baer & Company. In 2015, Joshua Baer & Company repurchased the first phase from Pytka. Later in 2015, the Pytka First Phase was purchased by its current owner, from Joshua Baer & Company. The first phase has been in the current owner’s collection since 2015.

Condition of the Pytka First Phase is excellent with less than 1% restoration. Corner tassels, side selvages, and top and bottom edge cords are 99% original. Less than 1% of the classic and late classic first phases in museum and private collections survived in comparable condition. The first phase shows no signs of wear. It was probably collected by its original owner from the Navajo woman who wove it.

The blue yarns are handspun Merino fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The black and charcoal gray yarns are handspun Merino fleece dyed in their yarns with synthetic dyes. The dark brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Merino fleece.

The Pytka First Phase contains a large amount of medium blue handspun yarns. The only other Navajo first phase with a comparable amount of medium blue handspun yarns is a Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket with Twelve Blue Bands, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Peterson First Phase. The Peterson First Phase is on exhibit at the Scottsdale Museum of the West, by loan from Tim Peterson, of Boston and Scottsdale.

A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket with Twelve Blue Bands,

Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Peterson First Phase.

A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket with Twelve Blue Bands, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Peterson First Phase.

The first phase measures 60 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven.

The Peterson First Phase is on exhibit at the Scottsdale Museum of the West.

The first phase is illustrated on Page 104 in Landowski, Courage and Crossroads, Selections from the Peterson Collection, 2014.

The Peterson First Phase is on exhibit at the Scottsdale Museum of the West. The first phase is illustrated on Page 104 in Landowski, Courage and Crossroads, Selections from the Peterson Collection, 2014.

The Peterson First Phase is ex- David Cook, Denver. In 2012, Edgar Smith, of New York, purchased the first phase from Cook. In 2014, Zaplin-Lampert Gallery in

Santa Fe, and Joshua Baer & Company, purchased the first phase from Smith. In December, 2014, Tim Peterson purchased the first phase from Zaplin-Lampert Gallery and Joshua Baer & Company.

The Peterson First Phase is ex- David Cook, Denver. In 2012, Edgar Smith, of New York, purchased the first phase from Cook. In 2014, Zaplin-Lampert Gallery in Santa Fe, and Joshua Baer & Company, purchased the first phase from Smith. In December, 2014, Tim Peterson purchased the first phase from Zaplin-Lampert Gallery and Joshua Baer & Company.

The first phase is in excellent condition with less than 1% restoration. Corner tassels, side selvages and top and bottom edge cords are 99% original. The first phase shows no signs of wear. It was probably collected by its original owner from the Navajo woman who wove it.

In the Peterson First Phase, the blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece. The Peterson First Phase is the only classic first phase, either Bayeta or Ute Style, with twelve wide bands of blue handspun yarns. All of the other classic first phase chief’s blankets in museum and private collections have eight stripes of blue handspun yarns.

Above: The Pytka First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870.

The first phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

Below: The Peterson First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

The first phase measures 60 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven.

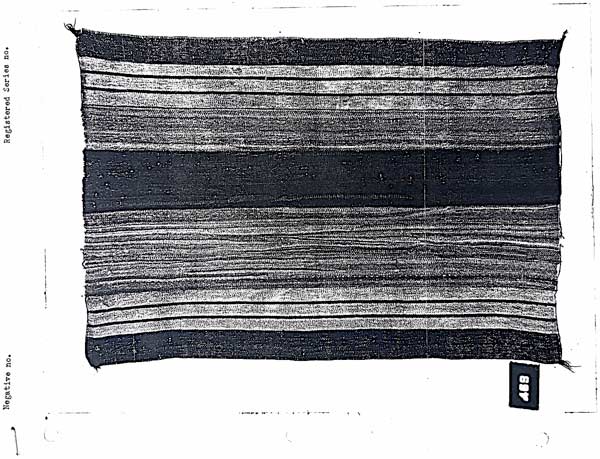

A Classic Twilled Manta with a Medium Blue Central Panel, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the Marcus Manta.

The manta measures 38 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

In the Pytka First Phase, the four panels of medium blue handspun yarns are unique to the first phase. There are no other classic or late classic first phases with four medium blue panels. Medium blue central panels do appear in a small group of classic and late classic Navajo mantas woven between 1850 and 1870. The Marcus Manta is the earliest of the Navajo mantas with blue central panels.

In 1939, the owner of the Marcus Manta was Dr. Harold Corbusier, of Santa Fe.

Dr. Corbusier and his wife, Louise, owned the Sol y Sombra estate on Old Santa Fe

Trail. Sol y Sombra means “sun and shadow.” Between 1984 and her death, in 1986,

Sol y Sombra belonged to Georgia O’Keefe. The estate later belonged to Paul Allen.

In 1939, the owner of the Marcus Manta was Dr. Harold Corbusier, of Santa Fe. Dr. Corbusier and his wife, Louise, owned the Sol y Sombra estate on Old Santa Fe Trail. Sol y Sombra means “sun and shadow.” Between 1984 and her death, in 1986, Sol y Sombra belonged to Georgia O’Keefe. The estate later belonged to Paul Allen.

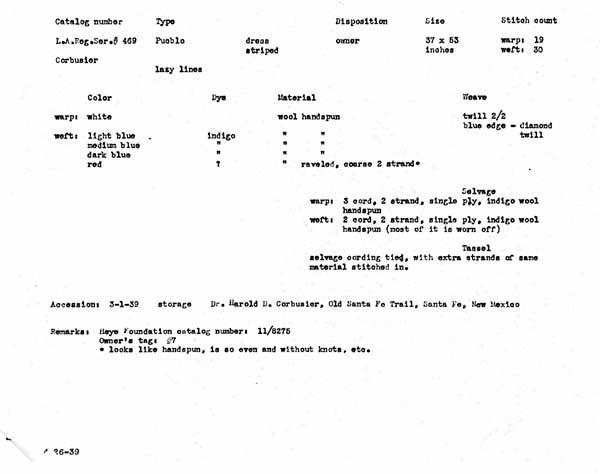

On March 1, 1939, H. P. Mera, the Staff Archaeologist at the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, photographed and cataloged the manta for Dr. Corbusier. Mera’s notes and photographs follow. Under “Remarks,” Mera notes that the manta has “Heye Foundation catalog number: 11/8275.” This means the Heye Foundation / Museum of the American Indian, in New York, deaccessioned the manta prior to 1939.

On March 1, 1939, H. P. Mera, the Staff Archaeologist at the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, photographed and cataloged the Marcus Manta. In his

notes, Mera attributes the manta as “Pueblo,” catalogs it as “dress striped,” identifies the manta’s red yarns as “raveled, coarse 2 strand,” identifies “Corbusier” as the owner, and mentions the manta’s “lazy lines.” It’s worth noting that while so-called lazy lines are common in classic and late classic Navajo mantas, lazy lines do not appear in Pueblo mantas.

On March 1, 1939, H. P. Mera, the Staff Archaeologist at the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, photographed and cataloged the Marcus Manta. In his notes, Mera attributes the manta as “Pueblo,” catalogs it as “dress striped,” identifies the manta’s red yarns as “raveled, coarse 2 strand,” identifies “Corbusier” as the owner, and mentions the manta’s “lazy lines.” It’s worth noting that while so-called lazy lines are common in classic and late classic Navajo mantas, lazy lines do not appear in Pueblo mantas.

A detail of the central panel of the Marcus Manta, Navajo, circa 1850.

The Marcus Manta is ex- Museum of the American Indian / Heye Foundation, New York. The Heye Foundation Catalog #11/8275 is stenciled onto one corner of the manta. It’s unknown how, when, or why the Museum sold the manta, or how it came to belong to Dr. Harold Corbusier. Corbusier died in Santa Fe, in 1950.

While it’s also unknown when either Corbusier or his estate sold the manta, by 1978 the manta was owned by Tony Berlant, of Santa Monica. In 1978, Berlant sold the manta to Christophe de Menil, of Houston and New York. Christophe de Menil is the daughter of Dominique and John de Menil, the co-founders of the Menil Collection, the Rothko Chapel, and the Cy Twombly Pavilion, in Houston.

In 1986, when I was working for Mac Grimmer at Morning Star Gallery in Santa Fe,

we bought the manta from the de Menil family and re-sold it to Dr. Bert Lies, of Santa Fe. In 1987, I started Joshua Baer & Company. In 1989, we exhibited the manta as part of Twelve Classics, first in Santa Fe, then in New York, at the Fall Antiques Show at the Pier. The New York version of Twelve Classics was curated by Bob Bishop, then the Director of the Museum of American Folk Art, in New York. The manta is illustrated

as Plate 2 in Twelve Classics, the exhibition catalog. In the catalog, I dated the manta

“circa 1850.”

In 1986, when I was working for Mac Grimmer at Morning Star Gallery in Santa Fe, we bought the manta from the de Menil family and re-sold it to Dr. Bert Lies, of Santa Fe. In 1987, I started Joshua Baer & Company. In 1989, we exhibited the manta as part of Twelve Classics, first in Santa Fe, then in New York, at the Fall Antiques Show at the Pier. The New York version of Twelve Classics was curated by Bob Bishop, then the Director of the Museum of American Folk Art, in New York. The manta is illustrated as Plate 2 in Twelve Classics, the exhibition catalog. In the catalog, I dated the manta “circa 1850.”

In 1991, we sold the manta to Linda and Stanley Marcus, of Dallas. It remained in the Marcus’s collection until 1998, when they consigned it to Sotheby’s. On December 2, 1998, the manta was sold as Lot #94 by Sotheby’s, New York, for $177,728, buyer’s premium included. The winning bidder was an art appraiser in New York. The appraiser later told me he’d purchased the manta on behalf of a couple who lived in New York.

During the 2000s, Joshua Baer & Company made two offers for the manta, through the New York appraiser. Both were declined. We still don’t know the identity of the couple who owns the manta.

The Pytka First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870.

The first phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Twilled Manta with a Medium Blue Central Panel, Navajo,

circa 1850, also known as the Marcus Manta. The manta measures

38 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Twilled Manta with a Medium Blue Central Panel, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the Marcus Manta. The manta measures 38 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

In the Marcus Manta, the red yarns are raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. All of the red yarns were raveled from the same bolt of lac-dyed bayeta. The dark blue and medium blue yarns are both handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarns with indigo.

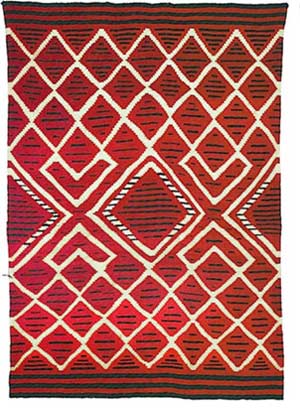

Above Left: The McKee Serape, Navajo, circa 1850.

Above Right: The Keam Serape, Navajo, circa 1871.

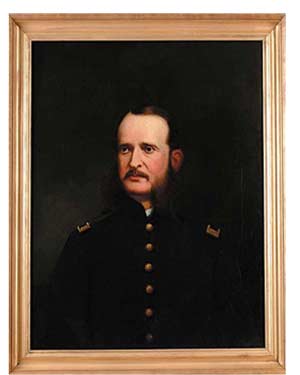

Below Left: A Portrait of Lieutenant Colonel James Cooper McKee, 1864.

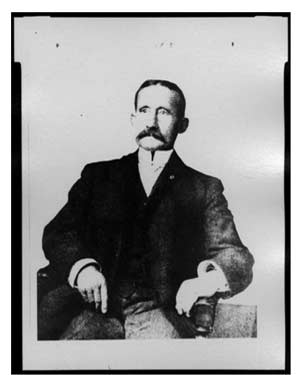

Below Right: An 1870s photograph of Thomas Varker Keam.

Left: A Classic Bayeta Serape, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the McKee Serape. The McKee Serape was collected during the late 1850s by Lieutenant Colonel James Cooper McKee, a surgeon with the United States Army. In 1867, McKee was stationed in Santa Fe, as Chief Medical Officer of the Army. In 1868, McKee was one of the signers of the United States Treaty with the Navajo. The McKee Serape follows the classic format of a red field with blue and white design elements, and no border. Between 1840 and 1860, this was the traditional format for classic Navajo bayeta serapes. The McKee Serape measures 85 inches long by 60 inches wide, as woven.

In 2007, the McKee Serape was purchased from Tony Berlant by Thomas Weisel of

San Francisco. In 2013, Weisel donated his collection of Native American art to the

de Young Museum in San Francisco. In 2014, classic blankets from Weisel’s collection, including the McKee Serape, went on exhibit at the de Young Museum. The McKee Serape is illustrated as Plate 59 in Lines On The Horizon, the exhibition catalog, by Matthew Robb and Jill D’Allesandro. Robb and D’Allesandro date the serape

“ca. 1850.”

Right: A Late Classic Serape with the initials “TVK” at Its Center, Navajo, circa 1871, also known as the Keam Serape. The serape was woven in 1871 at Fort Defiance for Thomas Varker Keam (1842-1904). Keam was an English merchant seaman who came to the United States in the 1860s, and became a trader with the Navajo. In 1869, at Fort Defiance, Keam married Astzan Ashihih, a Navajo woman who lived at the Fort.

In 1872, Keam was appointed Special Agent for the Navajo, and set up the first Navajo police force. In 1879, Keam opened a trading post near Fort Defiance. He later moved the post to what is now Keam's Canyon on the Hopi Reservation. The Keam Serape is in the collection of the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe. The serape measures 75 inches long by 51 inches wide, as woven.

In contrast to the McKee Serape, the Keam Serape is bordered. A large

checkered diamond dominates the field. Keam’s initials, “TVK,” appear at the center of the diamond. The Keam Serape illustrates the shift from classic serapes woven with traditional Navajo edge-to-edge designs to late classic serapes woven with the bordered, more decorative designs preferred by Anglo-Americans.

Left: A Classic Bayeta Serape, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the McKee Serape. The McKee Serape was collected during the late 1850s by Lieutenant Colonel James Cooper McKee, a surgeon with the United States Army. In 1867, McKee was stationed in Santa Fe, as Chief Medical Officer of the Army. In 1868, McKee was one of the signers of the United States Treaty with the Navajo. The McKee Serape follows the classic format of a red field with blue and white design elements, and no border. Between 1840 and 1860, this was the traditional format for classic Navajo bayeta serapes. The McKee Serape measures 85 inches long by 60 inches wide, as woven.

In 2007, the McKee Serape was purchased from Tony Berlant by Thomas Weisel of San Francisco. In 2013, Weisel donated his collection of Native American art to the de Young Museum in San Francisco. In 2014, classic blankets from Weisel’s collection, including the McKee Serape, went on exhibit at the de Young Museum. The McKee Serape is illustrated as Plate 59 in Lines On The Horizon, the exhibition catalog, by Matthew Robb and Jill D’Allesandro. Robb and D’Allesandro date the serape “ca. 1850.”

Right: A Late Classic Serape with the initials “TVK” at Its Center, Navajo, circa 1871, also known as the Keam Serape. The serape was woven in 1871 at Fort Defiance for Thomas Varker Keam (1842-1904). Keam was an English merchant seaman who came to the United States in the 1860s, and became a trader with the Navajo. In 1869, at Fort Defiance, Keam married Astzan Ashihih, a Navajo woman who lived at the Fort. In 1872, Keam was appointed Special Agent for the Navajo, and set up the first Navajo police force. In 1879, Keam opened a trading post near Fort Defiance. He later moved the post to what is now Keam's Canyon on the Hopi Reservation. The Keam Serape is in the collection of the Wheelwright Museum in Santa Fe. The serape measures 75 inches long by 51 inches wide, as woven.

In contrast to the McKee Serape, the Keam Serape is bordered. A large checkered diamond dominates the field. Keam’s initials, “TVK,” appear at the center of the diamond. The Keam Serape illustrates the shift from classic serapes woven with traditional Navajo edge-to-edge designs to late classic serapes woven with the bordered, more decorative designs preferred by Anglo-Americans.

The Pytka First Phase has three obvious anomalies: Its four blue bands, its square dimensions, and its three panels of alternating brown and white stripes. Considered separately, each of these three anomalies would distinguish the first phase from

all of the other classic and late classic Navajo first phases in museum and private collections.

Nineteenth century Navajo weaving was a deliberate process. The Navajo woman

who wove the Pytka First Phase took at least six months to finish it. The fact that three obvious anomalies appear in the same first phase raises the question: Why did the weaver deviate from established traditions on three different levels?

The presence of its black synthetic-dyed handspun yarns establishes the first phase

as late classic, which means it was probably woven between 1865 and 1870. During the classic period, from 1800 to 1865, Navajo weavers wove first phases for high-ranking members, or chiefs, of the Plains and Prairie tribes. After 1860, Navajo weavers started weaving blankets for Anglo-Americans. Many of those Anglo-American buyers were U. S. Army officers stationed either at Bosque Redondo or at Fort Defiance.

The Pytka First Phase has three obvious anomalies: Its four blue bands, its square dimensions, and its three panels of alternating brown and white stripes. Considered separately, each of these three anomalies would distinguish the first phase from all of the other classic and late classic Navajo first phases in museum and private collections.

Nineteenth century Navajo weaving was a deliberate process. The Navajo woman who wove the Pytka First Phase took at least six months to finish it. The fact that three obvious anomalies appear in the same first phase raises the question: Why did the weaver deviate from established traditions on three different levels?

The presence of its black synthetic-dyed handspun yarns establishes the first phase as late classic, which means it was probably woven between 1865 and 1870. During the classic period, from 1800 to 1865, Navajo weavers wove first phases for high-ranking members, or chiefs, of the Plains and Prairie tribes. After 1860, Navajo weavers started weaving blankets for Anglo-Americans. Many of those Anglo-American buyers were U. S. Army officers stationed either at Bosque Redondo or at Fort Defiance.

U. S. Army officers were, in every sense, the chiefs of Anglo-American culture, but they saw the world differently from the Arapaho, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, and Ute chiefs, who had been the primary buyers for first phases prior to 1860. Plains and Prairie cultures valued simplicity. Anglo-Americans valued complexity.

Some of the Army officers stationed at Fort Defiance commissioned Navajo weavers to weave serapes. Many of those commissioned serapes depart from the traditional patterns we see in pre-1865 classic bayeta serapes. If the Pytka First Phase was commissioned by an Army officer, he may have asked the weaver to weave him a first phase, but to make it more decorative than a traditional classic first phase. The Pytka First Phase may be a combination of the officer’s request and the Navajo weaver’s attempt to comply with it.