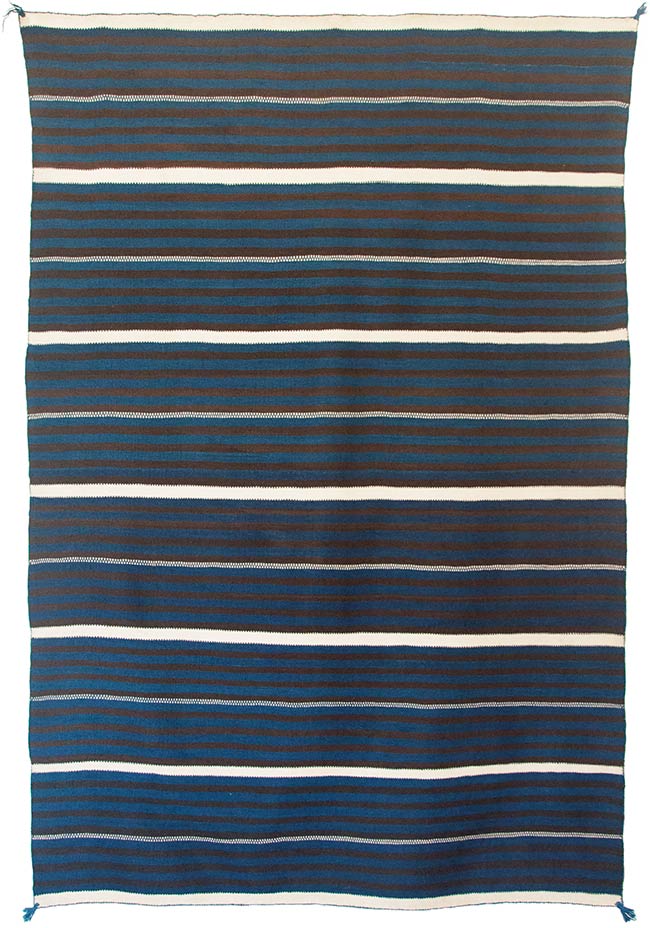

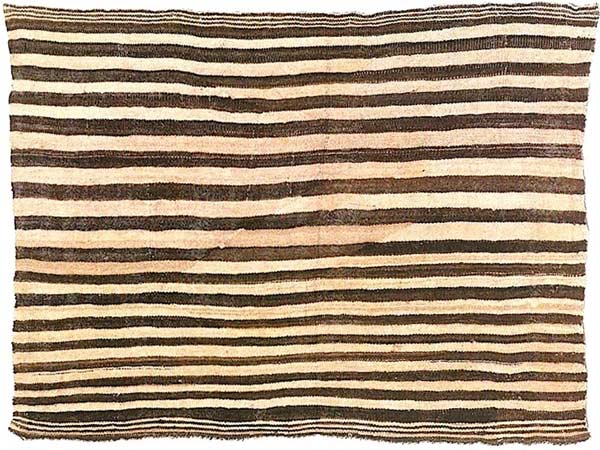

#5. An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830, also

known as the Schoch First Phase. The Schoch First Phase is the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with documented collection history. The first phase measures 51 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

#5. An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830, also known as the Schoch First Phase. The Schoch First Phase is the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with documented collection history. The first phase measures 51 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase was collected in St. Louis between 1833 and 1837 by Lorenz Alphons Schoch of Bern, Switzerland. Lorenz Schoch (1810-1866) was the son of a Swiss instruments manufacturer. (In Swiss-German, Schoch is pronounced “shock.”) The Schoch factory is still located in Burgdorf, Canton Berne.

In 1833, Lorenz Schoch arrived in St. Louis. For the next four years, he collected more than one hundred works of Native American art, including Iron Horn’s War Shirt, the Mato Tope Buffalo Hide, and the Schoch First Phase. Most of the pieces he collected were already antique when he acquired them.

Schoch left St. Louis in 1837. By 1842, he had returned to Switzerland with the first phase and the rest of the items he’d collected in St. Louis. After Schoch’s death, in 1866, the collection remained with his family until 1890.

In 1890, the Bernisches Historisches Museum (BHM), in Bern, Switzerland, purchased all of the items in Schoch’s collection from Schoch’s widow, Marie Karolina Ruef. The Schoch First Phase is cataloged by the museum as a “Sioux trade cloth.” [BHM Catalog #1890.410.0027.]

BHM’s catalog description raises the possibility that Schoch collected the first phase from a member of the Sioux tribe and never identified it as a classic Navajo blanket. The catalog description also raises the possibility that the Bernisches Historisches Museum is unaware of the first phase’s status as the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with documented collection history.

Above: The Schoch First Phase, in its current condition.

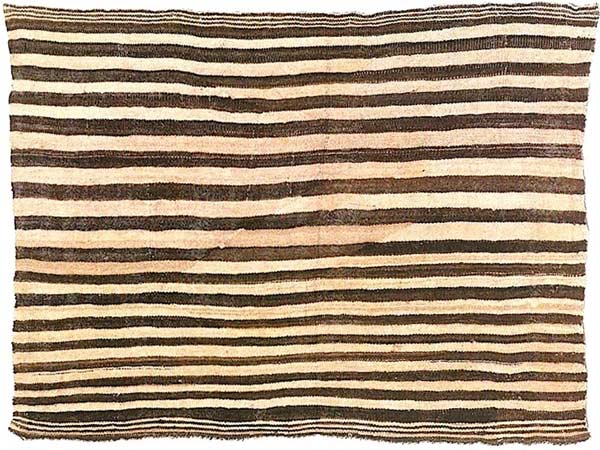

Below: A simulated version of the Schoch First Phase, without the holes in its field.

In the Schoch First Phase, the medium and dark brown yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece. Both the medium and dark brown handspun yarns exhibit the same color variegation that appears in the brown bands and central panels of other classic (pre-1865) first phases. The white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece. The white bands have the same ivory color that appears in other classic first phases. The Schoch First Phase is the only known example of a classic first phase, man or woman’s style, woven without blue handspun yarns.

The first phase is in excellent condition, with original corner tassels, side selvages, and top and bottom edge cords. All of the holes in the field are perforations. The first phase shows no signs of having been worn as a garment.

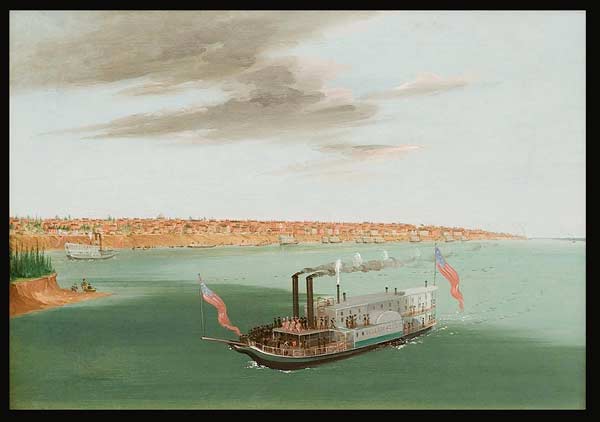

Saint Louis From The River Below, 1832, George Catlin (1796-1892)

Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. [SAAM #1985.66.311.]

“Saint Louis … is a flourishing town, of 15,000 inhabitants, and destined to be the great emporium of the West … [It] is the great depot of all the Fur Trading Companies to the Upper Missouri and Rocky Mountains, and their starting-place; and also for the Santa Fe, and other Trading Companies, who reach the Mexican borders overland, to trade for silver bullion, from the extensive mines of that rich country …

I have also made it my starting-point, and place of deposit, to which I send from different quarters, my packages of paintings and Indian articles, minerals, fossils, &c.,

as I collect them in various regions, here to be stored till my return; and where on my last return, if I ever make it, I shall hustle them altogether, and remove them to the East.”

“Saint Louis … is a flourishing town, of 15,000 inhabitants, and destined to be the great emporium of the West … [It] is the great depot of all the Fur Trading Companies to the Upper Missouri and Rocky Mountains, and their starting-place; and also for the Santa Fe, and other Trading Companies, who reach the Mexican borders overland, to trade for silver bullion, from the extensive mines of that rich country … I have also made it my starting-point, and place of deposit, to which I send from different quarters, my packages of paintings and Indian articles, minerals, fossils, &c., as I collect them in various regions, here to be stored till my return; and where on my last return, if I ever make it, I shall hustle them altogether, and remove them to the East.”

- George Catlin, Letters and Notes, Volume 2, Number 35, 1841.

The steamboat in Catlin’s Saint Louis From The River Below was The Yellowstone, owned and operated by John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. During the 1830s, The Yellowstone was the most reliable form of transportation between Saint Louis and the fur trading centers and Native American villages in the upper Missouri Valley.

Dacota Woman and Assiniboin Girl, Karl Bodmer, 1844.

Aquatint, from an original Bodmer watercolor done in June of 1833.

Illustrated as Plate 9 in Travels in the Interior of North America

by Prince Maximilian, Koblenz, 1849.

Illustrated as Plate 9 in Travels in the Interior of North America by Prince Maximilian, Koblenz, 1849.

On April 19, 1833, in Saint Louis, Prince Maximilian, of Prussia, and the Swiss artist, Karl Bodmer, of Zurich, boarded The Yellowstone for their journey to Fort Pierre and Fort Union, nine hundred miles north of Saint Louis. On June 1, 1833, at Fort Pierre, now South Dakota, Bodmer painted a portrait of Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin, a Teton Sioux woman.

In the portrait, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin is wearing beaded moccasins, beaded leggings,

a leather dress, and a buffalo robe decorated with stylized human figures. At her neck and shoulders, the robe has been folded back against itself, creating a collar of brown buffalo fur. When Prince Maximilian offered to buy her dress, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin said no, but later agreed to sell him her buffalo robe.

In the portrait, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin is wearing beaded moccasins, beaded leggings, a leather dress, and a buffalo robe decorated with stylized human figures. At her neck and shoulders, the robe has been folded back against itself, creating a collar of brown buffalo fur. When Prince Maximilian offered to buy her dress, Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin said no, but later agreed to sell him her buffalo robe.

Chan-Ccha-Nia-Teuin’s buffalo robe is in the collection of the Linden Museum, Stuttgart, Germany, by donation from Prince Maximilian. [LM #36102.]

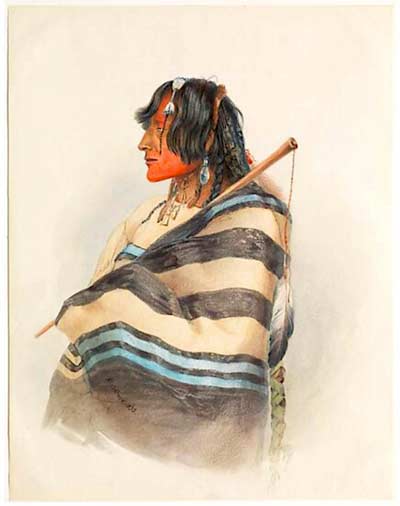

Kiasax (Bear-on-the-Left), 1833, by Karl Bodmer.

Watercolor on paper. The Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha.

On June 19, 1833, at Fort Pierre, Bodmer and Prince Maximilian debarked from the Yellowstone, boarded a larger steamboat, The Assiniboine, and sailed north. The Assiniboine’s destination was Fort Union, on the Missouri River. In 1833, Fort Union was the northernmost point in the United States reachable by steamboat. Among their fellow passengers on The Assiniboine was a Piegan Blackfoot chief named Kiasax—“Bear-on-the-Left.” Kiasax was on his way to Fort Union to reunite with his family.

Kiasax wore a large, woolen blanket around his shoulders and torso. The blanket had alternating brown and white bands, with pairs of blue stripes inside its brown bands and brown central panel. Kiasax wore the blanket with its top edge folded back into

a collar, in the manner of a buffalo robe. After being introduced to Kiasax, Bodmer painted a watercolor portrait of the Blackfoot chief. Bodmer’s portrait of Kiasax,

now in the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, is the earliest known painting of a Navajo chief’s blanket.

Kiasax wore a large, woolen blanket around his shoulders and torso. The blanket had alternating brown and white bands, with pairs of blue stripes inside its brown bands and brown central panel. Kiasax wore the blanket with its top edge folded back into a collar, in the manner of a buffalo robe. After being introduced to Kiasax, Bodmer painted a watercolor portrait of the Blackfoot chief. Bodmer’s portrait of Kiasax, now in the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, is the earliest known painting of a Navajo chief’s blanket.

Bodmer’s Kiasax establishes the first phase chief’s blanket as a trade item in the Missouri Valley during the early 1830s. The watercolor also establishes that pairs of blue stripes existed as design elements in a first phase woven no later than 1833.

Above: The Schoch First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800.

The Schoch First Phase is the only known example of a classic Navajo first phase

woven without blue handspun yarns.

The Schoch First Phase is the only known example of a classic Navajo first phase woven without blue handspun yarns.

Below: A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1840,

also known as the Morgan First Phase. Like the first phase worn by Kiasax,

the Morgan First Phase follows the traditional Ute Style format of alternating

brown and white bands with four pairs of blue stripes.

Below: A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Morgan First Phase. Like the first phase worn by Kiasax, the Morgan First Phase follows the traditional Ute Style format of alternating brown and white bands with four pairs of blue stripes.

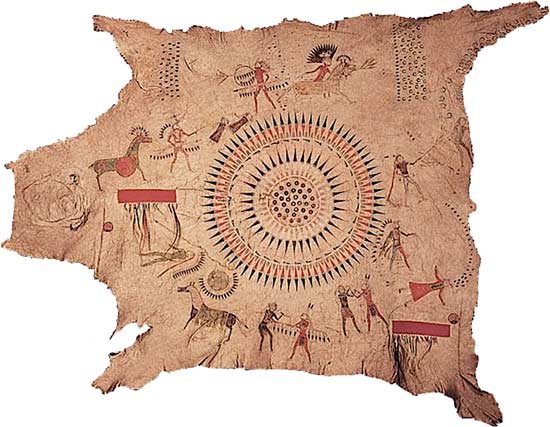

The Mato-Tope Buffalo Robe, Mandan, circa 1830.

Collected by Lorenz Alphons Schoch, in St. Louis, between 1833 and 1837.

The buffalo robe measures 63 inches long by 83 inches wide, as pictured.

Materials are native tanned leather, pigment, wool, porcupine quills, and human hair.

The buffalo robe measures 63 inches long by 83 inches wide, as pictured. Materials are native tanned leather, pigment, wool, porcupine quills, and human hair.

In 2014 and 2015, the Mato-Tope Buffalo Robe was exhibited at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris; at the Nelson Atkins-Museum, Kansas City; and at the Metropolitan Museum, New York; all as part of The Plains Indians – Artists of Earth and Sky. The robe is illustrated as Plate 42 in Torrence, The Plains Indians, Artists of Earth and Sky, 2014.

In Torrence, on Page 130, the robe’s caption, written by Evan Maurer, reads:

In 2014 and 2015, the Mato-Tope Buffalo Robe was exhibited at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris; at the Nelson Atkins-Museum, Kansas City; and at the Metropolitan Museum, New York; all as part of The Plains Indians – Artists of Earth and Sky. The robe is illustrated as Plate 42 in Torrence, The Plains Indians, Artists of Earth and Sky, 2014. In Torrence, on Page 130, the robe’s caption, written by Evan Maurer, reads:

One of Catlin’s illustrations shows a pictorial painted robe created by Mato Tope, who made the example we see here, as well as one for Maximilian that resides in the Linden Museum in Stuttgart. The current example, collected by Lorenz Alphons Schoch, a Swiss trader, in 1837, depicts eight of Mato Tope’s actions in battle against other Indian tribes.

The Mato-Tope Buffalo Robe is in the collection of the Bernisches Historisches Museum (BHM) in Bern, by purchase from Lorenz Schoch’s widow, Marie Karolina Ruef, in 1890. [BHM Catalog number: #1890.410.8.] In 1977, Judy Thompson wrote The North American Indian Collection, a catalog of BHM’s collection of Native American art. The Mato Tope Buffalo Robe appears as Figure 78 in the catalog. The following quote is from Thompson’s introduction to the catalog.

“Although European trade goods had reached the Plains area by the early 1700s, Plains Indians had little direct contact with white men until the mid-19th century. Collections as early as the Schoch material (1837) are therefore rare. Lorenz Alphons Schoch (1810-1866) was a Swiss from Burgdorf, Canton Berne. He went to the United States in 1833, where

he lived in St. Louis for several years and apparently came into contact with various Indian tribes in his role of merchant or trader. Schoch returned to Switzerland in 1842. His collection was purchased from his widow in 1890.”

“Although European trade goods had reached the Plains area by the early 1700s, Plains Indians had little direct contact with white men until the mid-19th century. Collections as early as the Schoch material (1837) are therefore rare. Lorenz Alphons Schoch (1810-1866) was a Swiss from Burgdorf, Canton Berne. He went to the United States in 1833, where he lived in St. Louis for several years and apparently came into contact with various Indian tribes in his role of merchant or trader. Schoch returned to Switzerland in 1842. His collection was purchased from his widow in 1890.”

The Schoch First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800.

This is a simulated version of the first phase, without the holes in its field.

The Schoch First Phase is the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with a documented collection history. It is the only known example of a classic (pre-1865) first phase woven without blue handspun yarns. It is the only classic first phase with the pattern of four white bands and four brown bands in the field above and below

its central panel. It is the only classic chief’s blanket woven in the man’s style with ticking between its brown and white bands.

The Schoch First Phase is the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with a documented collection history. It is the only known example of a classic (pre-1865) first phase woven without blue handspun yarns. It is the only classic first phase with the pattern of four white bands and four brown bands in the field above and below its central panel. It is the only classic chief’s blanket woven in the man’s style with ticking between its brown and white bands.

The first phase’s multiple design anomalies raise the possibility that it was woven during the late eighteenth century, before the traditional pattern of brown and white bands with pairs of thin blue stripes was established for classic first phases. Relative

to other classic first phases, the Schoch First Phase may not break the rules so much as it pre-dates them.

The first phase’s multiple design anomalies raise the possibility that it was woven during the late eighteenth century, before the traditional pattern of brown and white bands with pairs of thin blue stripes was established for classic first phases. Relative to other classic first phases, the Schoch First Phase may not break the rules so much as it pre-dates them.

Another possibility is that the Schoch first phase is a circa 1800 Navajo version of a Hopi Pösaala, a twilled manta also known as the Hopi bachelor blanket. Classic Hopi Pösaalas contain brown and white handspun yarns, but no blue yarns.

The two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. Geographically, the Hopi and the Navajo are close neighbors. Intermarriage between the two tribes has been common for four centuries. If a Navajo woman married into a Hopi family, it would have been consistent with her roles as a wife and a mother for her to weave a Pösaala influenced by both the Hopi and Navajo weaving traditions.

A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi

or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

The Pösaala measures 45 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

Dimensions are large for a classic Hopi Pösaala. The large dimensions raise the possibility that the Pösaala was woven by a Navajo woman who had married into

a Hopi family. The irregular widths of the Pösaala’s horizontal and vertical bands

support a Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi attribution.

Dimensions are large for a classic Hopi Pösaala. The large dimensions raise the possibility that the Pösaala was woven by a Navajo woman who had married into a Hopi family. The irregular widths of the Pösaala’s horizontal and vertical bands support a Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi attribution.

The Pösaala is fully twilled. The twilling appears as a diagonal pattern, as a diamond pattern, and as a herringbone pattern. While twilled patterns appear both in Hopi Pösaalas and Navajo mantas, the combination of three twilled patterns in the same manta is more common in classic Navajo mantas than in classic Hopi Pösaalas. Ticking, also called beading, appears in the two thin white lines that run horizontally across the Pösaala’s dark brown central panel.

The brown yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece, all from the same fleece. The white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece. The white yarns exhibit the same deep ivory color that appears in classic Navajo chief’s blankets woven prior to 1865.

Ex- private collection, New York. Acquired by the current owner in 2017.

Above: The Schoch First Phase, Navajo, circa 1800.

Below: A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi,

or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

Below: A Classic Pösaala, or Bachelor Blanket, Either Hopi, or Navajo-Woven-at-Hopi, circa 1850.

An Early Classic Moki Serape, Navajo, circa 1830.

The Moki Serape measures 71 inches long by 49 inches wide.

Ticking appears in all of the Moki Serape’s white bands and stripes.

An Early Classic Moki Serape, Navajo, circa 1830. The Moki Serape measures 71 inches long by 49 inches wide. Ticking appears in all of the Moki Serape’s white bands and stripes.

Moki serapes were woven longer than wide, with bands of alternating blue and brown stripes in their fields. Both the Hopi and the Navajo wove Moki serapes. “Moki” is a Navajo slang word for a Hopi person. Navajo-woven Moki serapes are identifiable by their corner tassels, side selvages, and lazy lines. While ticking is a common element in classic Moki serapes, it appears in only two classic Navajo chief’s blankets, the Schoch First Phase and the Morris First Phase.

The Moki Serape is ex- private collection, Portland, Oregon. In 2018, Joshua Baer & Company purchased the Moki serape from the Portland private collector.

The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

The center of the Early Classic Moki Serape, Navajo, circa 1830.

Ticking appears at the lower and upper edges of the white band.

The center of the Schoch First Phase, Navajo, circa 1800.

All of the first phase’s horizontal brown and white bands are ticked.

In Navajo blankets, ticking, also known as beading, is created by the placement of

a single dark weft adjacent to a single light weft. When one dark weft is placed above and below one light weft, the alternation between the dark and light yarns creates

a vertical column. When the column is stopped after three or four alternations, the visual result is the ticking pattern.

While ticking is common in classic Moki serapes, it appears in only two classic first phases: the Schoch First Phase and the Morris First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo,

circa 1750.

In Navajo blankets, ticking, also known as beading, is created by the placement of a single dark weft adjacent to a single light weft. When one dark weft is placed above and below one light weft, the alternation between the dark and light yarns creates a vertical column. When the column is stopped after three or four alternations, the visual result is the ticking pattern.

While ticking is common in classic Moki serapes, it appears in only two classic first phases: the Schoch First Phase and the Morris First Phase, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1750.

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style,

Navajo, circa 1750, also known as the Morris First Phase.

The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

An Early Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1750, also known as the Morris First Phase. The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

Ticking appears in the thin stripes at the top and bottom bands of the Morris First Phase, and in some but not all of its brown and white bands. The Schoch First Phase and the Morris First Phase are the only known examples of classic (pre-1865) first phases with ticking in their horizontals bands.

The Morris First Phase is illustrated as Figure 63a in Amsden, Navaho Weaving,

Its Technic and Its History, 1934. Amsden does not date the first phase.

The Morris First Phase is illustrated as Figure 68a in Amsden, Navaho Weaving, Its Technic and Its History, 1934. Amsden does not date the first phase.

The Morris First Phase is illustrated as Plate 49 in Wheat and Hedlund,

Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund describe the Morris First Phase as a “Navajo Shoulder Blanket (1750-1880), Banded” and note that it was

“Collected in 1937 by Earl H. Morris and Alfred V. Kidder from a Navajo grave

in Canyon de Chelly.” 1750 is the earliest circa date assigned by Wheat and

Hedlund to a Navajo chief’s blanket.

The Morris First Phase is illustrated as Plate 49 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund describe the Morris First Phase as a “Navajo Shoulder Blanket (1750-1880), Banded” and note that it was “Collected in 1937 by Earl H. Morris and Alfred V. Kidder from a Navajo grave in Canyon de Chelly.” 1750 is the earliest circa date assigned by Wheat and Hedlund to a Navajo chief’s blanket.

The Morris First Phase is in the collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, by donation from Earl Morris and Alfred Kidder. [MIAC Catalog #9150/12.] MIAC classifies the Morris First Phase as a grave good. The first phase is available for viewing only to Native Americans.

Condition is 95% original, with damage to the top and bottom edge cords. Corner tassels are missing. Stains exist throughout the field.

The blue yarns (in the barely visible thin blue stripes at the top and bottom of the first phase) are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

The Morris First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1750.

The first phase measures 49 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830.

The first phase measures 50 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

The Schoch First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830. The first phase measures 50 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven.

This is a simulated version of the Schoch First Phase,

without the holes in its field.

This is a simulated version of the Schoch First Phase, without the holes in its field.

What are the origins of the first phase chief’s blanket? How and when and where did the first phase become a valuable trade item among high-ranking members of the Plains and Prairie tribes? As the earliest Navajo blanket with a documented collection history, the Schoch First Phase offers some answers to those questions. While the first phase’s design anomalies raise their own questions, they also offer clues about the first phase’s history. The first phase’s condition offers another clue.

Aside from the obvious holes in its field, the Schoch First Phase is in excellent condition with no restorations. It’s unlikely that the first phase was ever worn as a garment. All of the holes in the field are perforations. None are the result of indigenous wear. The first phase’s corner tassels are original. Both the upper left and lower left corner tassels, as pictured, retain their original braiding. The first phase’s side selvages and top and bottom edge cords are original and 95% intact.

Of the approximately eighty classic first phases in museum and private collections, at least seventy-five have extensive damage to their corner tassels, side selvages, and edge cords. Even with its holes and stains, the original condition of its corner tassels, edge cords, and side selvages qualifies the Schoch First Phase as a condition rarity.

The possibility exists that Lorenz Schoch acquired the first phase in something approaching mint condition, and then used it to wrap some of the other items he collected during his time in Saint Louis, for shipment to Switzerland. If that is the case, then restoring the Schoch First Phase to its original condition would allow people to see the first phase as it appeared to Schoch when he purchased it in Saint Louis, between 1833 and 1837. It would also allow people to see the first phase as it appeared to the Navajo weaver who wove it, removed it from her loom, exchanged it for items of value, and started the first phase on its path—first to Saint Louis, and then to Switzerland.

The Schoch First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1800-1830. The first phase measures 50 inches long by 70 inches wide, as woven. The image is a simulated version of the Schoch First Phase, without the holes in its field.

The first phase was collected in Saint Louis between 1833 and 1837 by Lorenz Alphons Schoch (1810-1866), of Bern, Switzerland. In 1890, the Bernisches Historisches Museum (BHM), in Bern, purchased all of the items in Schoch’s collection of antique Native American art from Schoch’s widow, Marie Karolina Ruef. The Schoch First Phase is cataloged by the museum as a “Sioux trade cloth.” [BHM Catalog #1890.410.0027.]

The Schoch First Phase is the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with documented collection history.

The Bernisches Historisches Museum’s catalog description raises the possibility

that Schoch collected the first phase from a member of the Sioux tribe and never identified it as a classic Navajo blanket. The catalog description also raises the possibility that the museum is unaware of the first phase’s status as the earliest

known example of a Navajo blanket with documented collection history.

The Bernisches Historisches Museum’s catalog description raises the possibility that Schoch collected the first phase from a member of the Sioux tribe and never identified it as a classic Navajo blanket. The catalog description also raises the possibility that the museum is unaware of the first phase’s status as the earliest known example of a Navajo blanket with documented collection history.