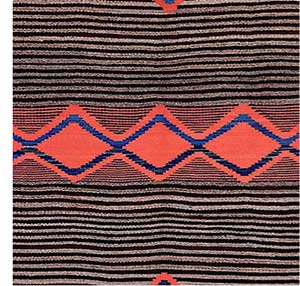

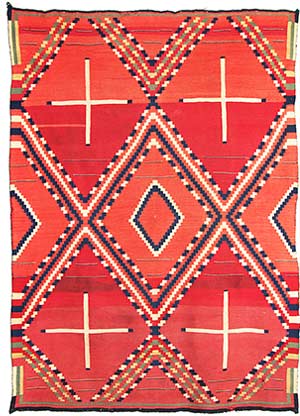

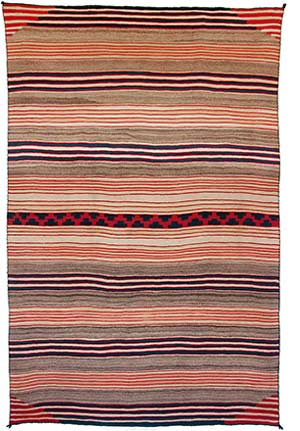

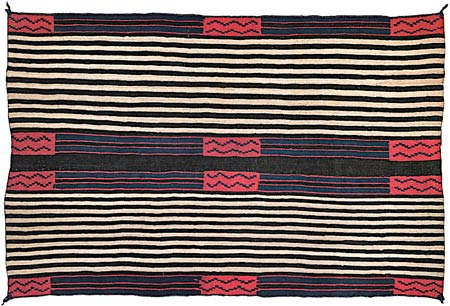

[Above]

A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860, also known as the Taylor Museum First Phase.

In the collection of the Taylor Museum, Colorado Springs.

The first phase measures 45 inches long by 57 inches wide, as woven.

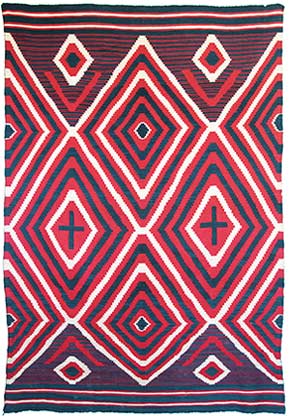

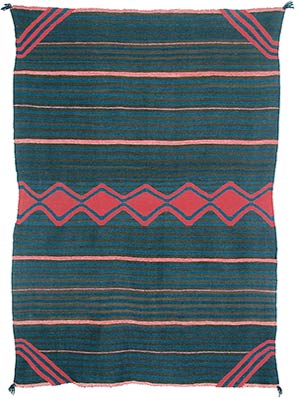

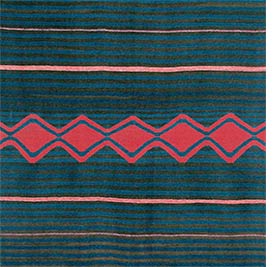

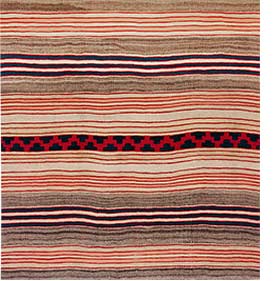

[Below]

A Late Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870, also known as the Pytka First Phase.

Ex- Joe Pytka, Los Angeles.

The first phase measures 54 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

What’s the Difference Between Classic and Late Classic?

Classic Navajo blankets were woven between 1800 and 1865. Classic blankets favor restraint and simplicity. Late classic Navajo blankets were woven between 1865 and 1875. Late classic blankets are more agitated and decorative than classic blankets.

In the two first phases pictured above, the Taylor Museum First Phase follows the traditional pattern of a woman’s style first phase, with four pairs of blue stripes in its three brown panels, and thin, alternating brown and grey stripes in the field above and below its central panel. The Pytka First Phase breaks from the traditional pattern. It’s the only known first phase chief’s blanket, either classic or late classic, with four blue bands separated by three panels of alternating brown and white stripes. Its square dimensions are also unique.

While it’s impossible to know why the weaver decided to depart from the traditional pattern, its four blue bands raise the possibility that the Pytka First Phase was commissioned by a US Army officer stationed in the southwest. The blue bands match the Union Blue color of an 1860s US Cavalry officer’s uniform.

Between 1800 and 1860, demand for Navajo chief’s blankets came from the Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, Shoshone, and Ute tribes. Demand for classic mantas and classic striped serapes came from the Acoma, Hopi, and Zuni Pueblos. Demand for bayeta serapes came from the Mexicans and the Spanish.

After the Mexican-American War of 1848, US Army expeditions started to arrive in the southwest. After 1860, demand for Navajo blankets came almost exclusively from Anglo-American buyers. Anglo-American design preferences were not the same as Native American preferences. Native Americans preferred simplicity in their blankets. Anglo-Americans preferred complexity. The late classic period of Navajo weaving was based on a collective effort by Navajo weavers to produce blankets that would appeal to Anglo-American buyers.

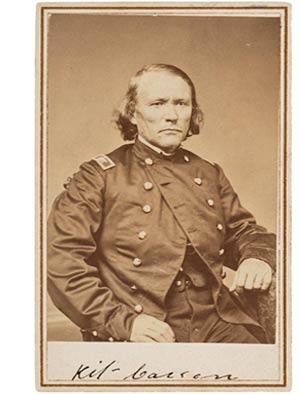

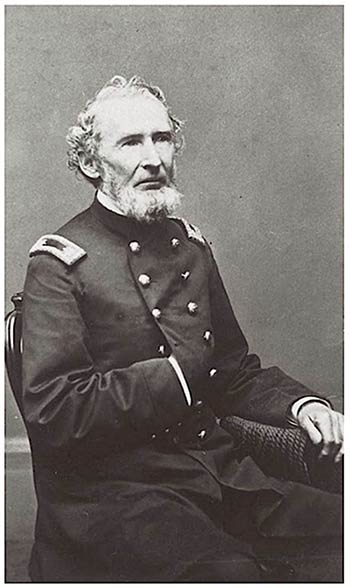

In 1864, acting on orders from Brigadier General James H. Carleton, Colonel Kit Carson led the US Army in a series of attacks on Navajo communities throughout the Four Corners. Carson ordered the Navajos’ flocks of sheep to be killed, and their peach orchards to be cut down. The Navajo refer to this period as Naahoondzood, "Time of Fear.” Carson’s attacks are remembered as the Siege of the Navajo.

Over 8,000 Navajos surrendered to Carson and the US Army. More than 2,000 Navajos died as they were forced to march four hundred miles to Bosque Redondo, also known as Fort Sumner, in eastern New Mexico Territory. Survivors of the march were imprisoned at Bosque Redondo from 1865 until 1868. Navajos remember the march as “The Long Walk” and refer to Bosque Redondo as “Hwéeldi.”

In June of 1868, at Bosque Redondo, Navajo tribal leaders and a group of US Army officers signed the United States Treaty with the Navajo. After the signing, the Navajo survivors were allowed to walk back from Bosque Redondo to their homes and territories in the Four Corners.

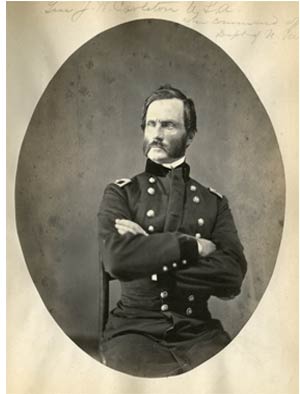

Left: Brigadier General James H. Carleton, 1866.

Right: Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson, 1863.

“For a long time past the Navajoe [sic] Indians have murdered and robbed the people of New Mexico. Last winter when eighteen of their chiefs came to Santa Fe to have a talk, they were warned—and were told to inform their people— that for these murders and robberies the tribe must be punished, unless some binding guarantees should be given that in [the] future these outrages should cease. No such guarantees have yet been given: But on the contrary, additional murders, and additional robberies have been perpetrated upon the persons and property of unoffending citizens. It is therefore ordered that Colonel Christopher ‘Kit’ Carson, with a proper military force proceed without delay to a point in the Navajoe country known as Pueblo Colorado [now Ganado, Arizona], and there establish a defensible Depot for his supplies and Hospital; and thence to prosecute a vigorous war upon the men of this tribe until it is considered at these Head Quarters that they have been effectually punished for their long continued atrocities.”

- Brigadier General James H. Carleton, General Order No. 15, June 15th 1863.

“...all those Navajoes who claimed not to have murdered and robbed the inhabitants must come in [surrender] and go to the Bosque Redondo [a concentration camp at Fort Sumner, on the Pecos River, in east central New Mexico], where they would be fed and protected until the war was over.”

- Brigadier General James H. Carleton, in a letter to Lieutenant Colonel J. Francisco Chavez, June 23rd 1863

Both of Carleton’s quotes are from the book Navajo Roundup by L. C. Kelly, 1970. Notations in [brackets] are Kelly’s.

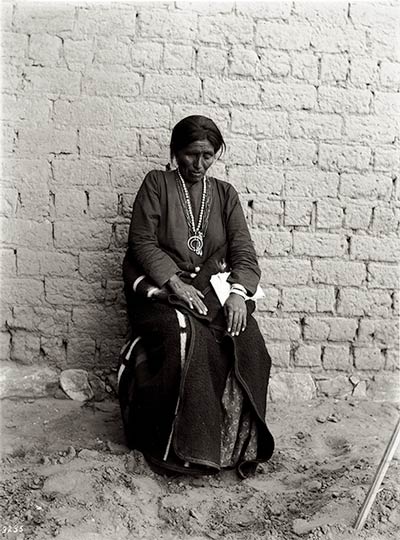

Manuelito’s blind daughter, 1901, by Charles C. Pierce.

Manuelito was a Navajo war chief. In 1866, Manuelito walked with his clan to Bosque Redondo. On June 1, 1868, Manuelito was one of the signers of the United States Treaty with the Navajo. The Treaty allowed the Navajo to return to their homes and territories in the Four Corners.

“It was said that those ancestors were on the Long Walk with their daughter, who was pregnant and about to give birth… The daughter got tired and weak and couldn't keep up with the others or go further because of her condition. So my ancestors asked the Army to hold up for a while and to let the woman give birth, but the soldiers wouldn't do it. They forced my people to move on, saying that they were getting behind the others. The soldier told the parents that they had to leave their daughters behind. ‘Your daughter is not going to survive, anyway; sooner or later she is going to die,’ they said in their own language. ‘Go ahead,’ the daughter said to her parents, ‘things might come out all right with me,’ But the poor thing was mistaken, my grandparents used to say. Not long after they had moved on, they heard a gunshot from where they had been a short time ago.”

From Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period, 1973. Edited by Ruth Roessel.

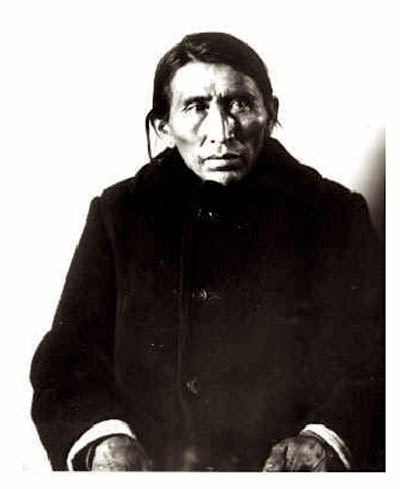

Pehslaki Etsedi, a survivor of Bosque Redondo. In 1867, as a young man, Etsedi walked with his family and clan from Fort Wingate to Bosque Redondo. The photograph was taken in 1901.

“The day after that we came to Toseto [Old Fort Wingate]; there were many soldiers here. That was the first time I had seen a wagon. They gave us flour but we didn't know how to cook it and we could not use it. We stayed there two days and the soldiers came back from Zuni. The third day the soldiers put the old women and children in five wagons pulled by mules and we traveled to Tsch Kish To Hee [near Cubero, NM]. The next day I did not ride in the wagon; they went too slowly, so I walked. The mules could not keep up with the big Navajo sheep and goats. We came near to To Thlanee [Laguna Pueblo]. The next night we stayed near Nah Se Se Tee Yay, at a spring. There my mother's uncle died; he was a very old man. The soldiers buried him and we traveled all that day and all the next night. At sunrise we came to a town by the side of a river [Atricso or Isleta?]; the river was wide with many trees along it; but there was no water then. We called it Nokai Bi To [Rio Grande]. We ate at this town by the river, then we went up the river on the west side. When the sun was straight up in the sky we crossed the river and were in a large town. We went to a big corral made of mud blocks near the river; in the corral were two bells hanging from posts; we called this place Bay Il Deel Da Si Neel [Albuquerque]. We camped inside the corral; it was full of Navajos. The Mexicans gave us corn and the soldiers gave us hard pieces of bread and some meat in skins; a few of our people had brought their metates so we ground the bread and corn on them and made a mush with the meat in it. We stayed there two days and while we were here Hosteen Deel died. When we left this place we went up the river until we were north of the mountains; then we went a little more east and came to a village with people like Hopis living there. We spent a night there, then crossed some hills and came to a village which the soldiers called "Walla"; we camped near there. In the morning we went about five miles and came to a place where the roads came together. We called it Na Ah Dinay. After we left Na Ah Dinay we went southeast and went that way for three days until we came to Bosque Redondo.”

From The Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, by Peshlakai Etsedi, as told to Sallie Pierce Brewer, Museum Notes: Museum of Northern Arizona, 9:#11, May, 1937.

Ti co bu sha, Son of Barboncito, by Valentin Wolfenstein (1845–1909). Taken at Bosque Redondo, in 1868. Albumen print with hand-coloring. In the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum [37:2019].

Ti co bu sha is wearing a third phase chief’s blanket, woman’s style.

“When men and women talk about Hwéeldi, they say it is something you cannot really talk about, or they say that they would rather not talk about it. Every time their thoughts go back to Hwéeldi, they remember their relatives, families, and friends who were killed by the enemies. They watched them die, and they suffered with them, so they break into tears and start crying. That is why we only know segments of stories, pieces here and there. Nobody really knows the whole story about Hwéeldi. This story was not to be retold, because if you repeat the story, it will happen again to the Navajos.”

- Mary Pioche (Hwéeldi Baa Hané, 1989:99)

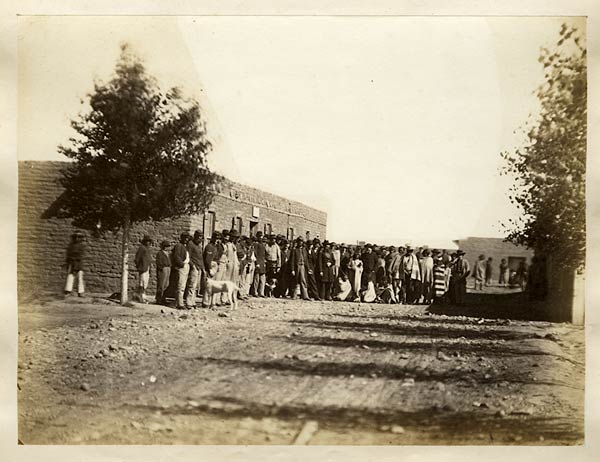

Navajo captives and US Army soldiers at Bosque Redondo, 1866.

On the far right, a Navajo woman is wearing a chief’s blanket.

Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, Santa Fe. [#001817.]

Navajo captives and US Army soldiers at Bosque Redondo, 1866. On the far right, a Navajo woman is wearing a chief’s blanket. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, Santa Fe. [#001817.]

“As I have said, our ancestors were taken captive and driven to Hwéeldi for no reason at all. They were harmless people, and, even to date, we are the same, holding no harm for anybody... Many Navajos who know our history and the story of Hwéeldi say the same.”

– Howard Gorman, Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period, 1973.

Edited by Ruth Roessel.

[Above]

A Classic Second Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1850, also known as the New Orleans Second Phase.

The second phase measures 59 inches wide by 41 inches long, as woven.

Ex- Stephen Loeb, New Orleans.

[Below]

A Late Classic Second Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1865, also known as the McNett Second Phase.

The second phase measures 42 inches long by 63 inches wide, as woven.

Ex- Rachel Eleanor Griffin McNett, Fort Defiance, Arizona Territory.

The McNett Second Phase is illustrated as Plate 27 in Bonar, Woven by the Grandmothers, 1996. According to Bonar, the second phase was collected in 1870 at Fort Defiance, Arizona Territory, by Rachel Eleanor Griffin McNett, the wife of Dr. Robert McNett, a US Army physician at Fort Defiance. In 1961, Mrs. Harvé Reed Stuart, Rachel McNett’s daughter, donated the second phase to the Museum of the American Indian / Heye Foundation, in New York City. The McNett Second Phase is now in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC. [NMAI#23.921].

The McNett Second Phase is illustrated as Plate 74 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund date the second phase “1865-1870*” and note the McNett collection history.

In classic second phases, woven in both the man’s and woman’s styles, design elements tend to be horizontal red rectangles with no decorative aspects inside the rectangles. The New Orleans Second Phase follows the traditional pattern of pairs of red rectangles and pairs of blue bands in its top and bottom panels, but deviates from traditional pattern in its central panel, where there are three sets of three solid red rectangles separated by two sets of three blue bands.

In late classic second phases, the horizontal red rectangles often contain small, decorative elements, like crosses, thin stripes, or terraced diagonals. In the McNett Second Phase, thin red stripes connect the twelve red rectangles. Each rectangle encloses a pair of matched terraced diagonals, composed of small dark blue squares.

Fort Defiance, also known as Fort Canby, is on the Navajo Reservation in Apache County, Arizona. In 1863, Fort Canby was the base of operations for Colonel Kit Carson and the US Army’s assault on the Navajo.

[Above]

A Classic Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860.

The third phase measures 37 inches long by 56 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1860. The third phase measures 37 inches long by 56 inches wide, as woven.

[Below]

A Late Classic Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870,

also known as the Durango Third Phase, Woman’s Style.

A Late Classic Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Woman’s Style, Navajo, circa 1870, also known as the Durango Third Phase, Woman’s Style.

Ex- Mark Winter, and the Durango Collection, Pagosa Springs, Colorado.

The third phase measures 48 inches long by 58 inches wide, as woven.

Ex- Mark Winter, and the Durango Collection, Pagosa Springs, Colorado. The third phase measures 48 inches long by 58 inches wide, as woven.

Between 1780 and 1860, Navajo weavers had two sources of red yarn: Yarns raveled from red bayeta, a machine-woven woolen fabric piece-dyed with cochineal in European textile mills; and Saxony yarn, a machine-spun European knitting yarn dyed in the skein with cochineal, in woolen mills in Germany. Cochineal dye was available from Mexico, but Navajo weavers lacked the mordants necessary to strip lanolin from their fleeces, so the cochineal could not saturate their handspun yarns. With one or two exceptions, there are no classic blankets containing red handspun yarns dyed with cochineal by Navajo weavers.

Synthetic dyes were invented in England, in 1856, by William Henry Perkin (1838-1907). Perkin was an eighteen-year-old student at London’s Royal College of Chemistry when he synthetized mauvine, or aniline purple, with chemicals he extracted from coal tar. Perkin filed for a patent in August of 1856. In 1857, he opened his first mauvine factory in Greenford Green, near London.

By 1859, synthetic-dyed cotton, silk, and woolen fabrics were available worldwide, in colors ranging from mustard yellow to China red, Prussian blue, royal purple, and tangerine orange. Perkin’s invention of synthetic dyes effectively replaced cochineal, lac, and madder as the world’s sources of red dye.

Between 1865 and 1870, synthetic-dyed American Flannel replaced bayeta as the Navajos’ primary source for raveled red yarn, and synthetic-dyed orange machine-spun knitting yarns replaced red Saxony yarns. The shift from red to orange is the visual reference point for the late classic period. The Durango Third Phase has classic designs and proportions. What makes it late classic are its areas of orange American flannel and orange machine-spun knitting yarns.

By 1875, spools of machine-spun, synthetic-dyed knitting yarns from Germantown, Pennsylvania, began arriving in the southwest. Germantown yarns were available in a wide spectrum of colors. By 1880, Navajo weavers had adapted to weaving eye-dazzler serapes with Germantown yarns. The tradition of raveling either red yarns from bayeta or orange yarns from American Flannel and re-weaving those raveled yarns into their blankets was no longer a day-to-day part of weaving a Navajo blanket.

[Left]

A Classic Bayeta Serape with a Large Aggregate Diamond, Navajo, circa 1840,

also known as the Yorba Serape. The serape measures 76 inches long

by 51 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Bayeta Serape with a Large Aggregate Diamond, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Yorba Serape. The serape measures 76 inches long by 51 inches wide, as woven.

Ex- Bernardo Antonio Yorba II (1801-1858), Rancho Cañón de Santa Ana,

Alta California. Yorba Linda, California, was named after Bernardo Yorba II.

Bernardo Yorba II collected the serape during the 1840s. The serape remained

in the Yorba family until 2008.

Ex- Bernardo Antonio Yorba II (1801-1858), Rancho Cañón de Santa Ana, Alta California. Yorba Linda, California, was named after Bernardo Yorba II. Bernardo Yorba II collected the serape during the 1840s. The serape remained in the Yorba family until 2008.

[Right]

A Late Classic Serape with a Spider Woman Opening, Navajo,

circa 1865, also known as the Lillie Serape. The serape measures

72 inches long by 53 inches wide, as woven.

A Late Classic Serape with a Spider Woman Opening, Navajo, circa 1865, also known as the Lillie Serape. The serape measures 72 inches long by 53 inches wide, as woven.

Ex- Charles A. Lillie (1857-1941), Angel Camp, California.

Ex- Prescott Knock, Lillie’s great-great grandson, Lafayette, Colorado.

Ex- David Cook, Denver, from Knock, 2012.

Purchased by Sally and Peter Herfurth, of Minneapolis, 2013, from Cook.

In the collection of the Minneapolis Art Institute, Minneapolis,

by donation from Sally and Peter Herfurth, 2022.

Ex- Charles A. Lillie (1857-1941), Angel Camp, California. Ex- Prescott Knock, Lillie’s great-great grandson, Lafayette, Colorado. Ex- David Cook, Denver, from Knock, 2012. Purchased by Sally and Peter Herfurth, of Minneapolis, 2013, from Cook. In the collection of the Minneapolis Art Institute, Minneapolis, by donation from Sally and Peter Herfurth, 2022.

Classic bayeta serapes express composure. Late classic serapes express agitation.

In classic bayeta serapes, it’s unusual to see more than three colors of yarn: blue, red, and white. In late classic serapes, it’s not unusual to see raveled red yarns from two different bolts of bayeta; raveled American flannel from two bolts of flannel; Saxony yarns from multiple sources; green and yellow handspun Merino fleece dyed in the yarn with vegetal dyes; midnight blue handspun Merino fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo; and un-dyed white handspun Merino fleece.

The shift from the variegated blue handspun yarns in classic serapes to the midnight blue handspun yarns in late classic serapes was an attempt by certain Navajo weavers to appeal to the Anglo-American preference for flat colors. For most Anglo-Americans in the 1860s, the Industrial Revolution was just getting started. Machine-made products offered a mathematical, standardized precision that made Anglo-Americans feel safe and secure. It would be another century before Anglo-American culture began to appreciate the beauty and idiosyncrasies of handmade goods.

For the Navajo, the classic period had been an era when Navajo weavers accumulated wealth for their families. That wealth came from weaving bayeta serapes and chief’s blankets that were the most valuable blankets in the world, and exchanging those blankets for food, horses, rifles, sheep, silver, and other items of value. The six months to a year that it took to weave a classic blanket was time well spent, because there was always an end user. The end user paid the going rate for the finished product, because the chief’s blanket and the bayeta serape were both accepted as stores of value and as trade items throughout the Great Plains, the Missouri Valley, and the Rio Grande Valley.

The late classic period inverted the status quo. Anglo-Americans appreciated Navajo blankets as “Indian-made” souvenirs, but thought they might not be as well made as machine-made blankets. As Anglo-American preferences for agitated designs, flat colors and precise proportions took over, Navajo weavers did their best to weave blankets that met those preferences. This is the legacy of the late classic period.

[Left]

A Classic Moki Serape with Terraced Diamonds, Navajo, circa 1855,

also known as the Ernst Moki Serape. Ex- Margo and John Ernst, New York.

The Moki Serape measures 70 inches long by 48 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Moki Serape with Terraced Diamonds, Navajo, circa 1855, also known as the Ernst Moki Serape. Ex- Margo and John Ernst, New York. The Moki Serape measures 70 inches long by 48 inches wide, as woven.

The Ernst Moki Serape is illustrated as Plate 32 in Selser and Kaufman,

The Navajo Weaving Tradition, 1985. Selser and Kaufman date the serape “c. 1865.”

The Ernst Moki Serape is illustrated as Plate 32 in Selser and Kaufman, The Navajo Weaving Tradition, 1985. Selser and Kaufman date the serape “c. 1865.”

[Right]

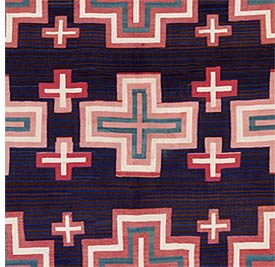

A Late Classic Moki Serape with Large Crosses, Navajo, circa 1865,

also known as the Berlant Moki Serape. Ex- Tony Berlant, Santa Monica.

The Moki Serape measures 73 inches long by 56 inches wide, as woven.

A Late Classic Moki Serape with Large Crosses, Navajo, circa 1865, also known as the Berlant Moki Serape. Ex- Tony Berlant, Santa Monica. The Moki Serape measures 73 inches long by 56 inches wide, as woven.

The Berlant Moki Serape was exhibited as part of The Navajo Blanket, 1972-1974,

at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, et alia. The Berlant Moki Serape

is illustrated as Plate 40 in Berlant & Kahlenberg, Walk in Beauty, 1977;

and as Figure 5 in Baer, The Last Blankets, 1997.

The Berlant Moki Serape was exhibited as part of The Navajo Blanket, 1972-1974, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, et alia. The Berlant Moki Serape is illustrated as Plate 40 in Berlant & Kahlenberg, Walk in Beauty, 1977; and as Figure 5 in Baer, The Last Blankets, 1997.

These two Moki serapes illustrate the differences between classic and late classic blankets. The classic Moki is understated, but it delivers its message about atmosphere, distance, and space, with emphasis. The late classic Moki has as much to say about atmosphere, distance, and space as the classic Moki. It just uses all of its colors, crosses, and stripes to make that statement. In the late classic Moki, the contrast between foreground and background is extraordinary. If you spend time watching the Moki, you can almost feel yourself falling into the space between its crosses.

Raveled bayeta dyed with cochineal, with lac, or with combinations of cochineal and lac, does not fade, even in direct sunlight. Red Saxony yarns dyed with cochineal do not fade. Indigo-dyed handspun yarns do not fade. Un-dyed brown and un-dyed white handspun yarns do not fade. When we look at a classic Navajo blanket, we see the colors the weaver saw while she wove the blanket.

Synthetic-dyed yarns will fade, in either direct or indirect sunlight. Raveled American flannel will fade after exposure to as little as a year of direct sunlight, and after three to five years of indirect sunlight. Synthetic-dyed knitting yarns, including Germantown yarns, are especially vulnerable to fading. There are many late classic and Germantown serapes in museums and private collections with “A” sides and “B” sides.

In the Berlant Moki, the upper and lower large crosses were woven with raveled bayeta dyed with cochineal. Its central crosses were woven with synthetic-dyed raveled American Flannel. A few of the Moki’s smaller crosses, and sections of its lower large crosses, were woven with American Flannel. In person, the areas of American Flannel are between 5% and 10% faded from their original colors. In photographs, the pale orange gives the Moki the appearance of being more faded than it is in person.

Both of these Moki serapes are masterpieces of Navajo weaving. To say that the classic Moki is a better or more valuable serape than the late classic Moki would be an absurd thing to say. Any experienced collector of Navajo blankets would be happy to own either of these Mokis, and even happier to own them both.

[Left]

A Classic Child’s Blanket with Grey Bands, Navajo, circa 1855.

The child’s blanket measures 49 inches long by 32 inches wide, as woven.

A Classic Child’s Blanket with Grey Bands, Navajo, circa 1855. The child’s blanket measures 49 inches long by 32 inches wide, as woven.

[Right]

A Late Classic Child’s Blanket with Grey Bands, Navajo, circa 1865,

also known as the Dewart Child’s Blanket. Ex- Anne Dewart, Boston.

The child’s blanket measures 51 inches long by 31 inches wide, as woven.

A Late Classic Child’s Blanket with Grey Bands, Navajo, circa 1865, also known as the Dewart Child’s Blanket. Ex- Anne Dewart, Boston. The child’s blanket measures 51 inches long by 31 inches wide, as woven.

One of the earliest classic Navajo blankets with a documented collection history is a Classic Child’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1845, also known as the Randall Child’s Blanket.

The Randall Child’s Blanket was collected in 1847 by Burton Randall (1805 – 1886), an Assistant Surgeon in the US Army. Randall collected the child’s blanket during the Mexican-American War. The child’s blanket is illustrated as Plate 1 in Baer, Collecting the Navajo Child’s Blanket, 1986; and dated: “circa 1845.” The child’s blanket is also illustrated on Page 248 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund refer to the child’s blanket as “Navajo Serape (ca. 1847*)”.

Other classic child’s blankets were woven between 1850 and 1860, including the Classic Child’s Blanket with Grey Bands, pictured above. However, the child’s blanket was not woven in quantities until after 1860. Between 1860 and 1870, more child’s blankets were woven than during any other decade of the nineteenth century.

The reason for the large number of child’s blankets woven during the 1860s was time. Between 1800 and 1860, a Navajo woman wove a classic bayeta serape for the purpose of weaving the serape. The amount of time it took to weave the serape was secondary to the effort that went in to weaving a blanket of great value. In the case of chief’s blankets and bayeta serapes, it took at least a year to start and finish the blanket.

After 1860, the economic and political hardships associated with the arrival and presence of the US Army compelled Navajo weavers to stop weaving blankets that took a year to finish. Weaving a blanket that could be finished and sold in two or three months was a matter of survival. Weaving a blanket for the sake of weaving it was no longer an option. Weaving a blanket in order to finish it was the issue. This meant weaving smaller serape-style blankets that incorporated some of the design elements associated with full-sized bayeta serapes. While some classic child’s blankets have the same restraint and simplicity we see in classic serapes, many child’s blankets woven during the 1860s have more in common with late classic serapes than with classic serapes.

The Randall Child’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1845.

The child’s blanket measures 48 inches long by 30 inches wide, as woven.

The Randall Child’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1845. The child’s blanket measures 48 inches long by 30 inches wide, as woven.

In the child’s blanket, the upper, middle, and lower panels of interlocking designs may be stylized versions of corn stalks and / or ears of corn.

The Randall Child’s Blanket was collected in 1847 by Dr. Burton Randall (1805-1886). Born in Maryland, Randall was appointed Assistant Surgeon in the US Army, in 1832. Randall’s military record included posts as an Army surgeon in the south, the southwest, and in Mexico. (See below.)

The Randall Child’s Blanket is ex- Fred Boschan (1916-2015), of Philadelphia. The child’s blanket is in the collection of the University of Colorado Museum, Boulder, by donation from Fred Boschan. [UCM Catalog #39310.]

In 1986, the Randall Child’s Blanket was exhibited as part of Collecting The Navajo Child’s Blanket, an exhibition of Navajo child’s blankets at Morning Star Gallery, in Santa Fe. The child’s blanket was illustrated as Plate 1 in Baer, Collecting the Navajo Child’s Blanket, 1986, the exhibition catalog; and dated “circa 1845.”

The Randall Child’s Blanket is illustrated on Page 248 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, 2003. Wheat and Hedlund refer to the child’s blanket as “Navajo Serape (ca. 1847*),” and state that the child’s blanket was “Collected by Burton Randall in 1847 while with the army of occupation in New Mexican territory; to Fred Boschan collection.” Under Notes, Wheat states: “This is the earliest known, documented, whole Navajo serape.”

Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Burton Randall, circa 1875. From the War Department’s Records, Washington, DC.

Between 1832 and 1838, Randall was engaged in military campaigns against the Choctaw, Delaware, Osage, and Pawnee tribes. In 1835, Randall was engaged in

the forced migration of the Creek tribe beyond the Mississippi. In 1842, he was engaged in the Second Seminole War, in Florida. In 1847 and 1848, Randall was engaged in the Army’s Invasion and Occupation of Mexico. Randall collected the child’s blanket in Mexico.

In 1865, Randall was named Brevet Lieutenant Colonel, U. S. Army, for faithful and meritorious service during the Civil War. In 1878, Randall was admitted to the Government Hospital for the Insane, in Washington, D.C. He died in Washington on February 8, 1886, at the age of 81.

Upon learning of his father’s death, also on February 8, 1886, Randall’s son, John K. Randall, a lawyer and librarian at Baltimore’s Mercantile Library, committed suicide, at the age of 32, by shooting himself in the heart. Dual funerals were held at St. Anne’s Church, in Annapolis, on February 10, 1886.