Navajo Serapes

“Serape”comes from the Spanish word “sarape” or “zarape,”— “a full-length man’s shawl.” Zarape came into use between 1550 and 1800, during the Spanish occupation of Mexico. Zarape may derive from the Nahuatl tzalan, or from the Tarascan tsarakua. Both tzalan and tsarakua refer to a man’s garment.

Spanish priests, settlers, and soldiers in colonial Mexico adopted zarape because zarape sounded like sarapi—Old Iranian for “a pleated robe.” Sarapi was in use in ancient Persia by 630 BC, and in ancient Greece by 430 BC. In ancient Persian, sar meant “head” and pay meant “foot.”

Sarapi referred to a garment that covered the wearer “from head to foot.” By 400 BC, in ancient Persian, sarapi meant “a robe of honor.” In Iran, nineteenth century knotted carpets woven in and around the Heriz District, forty miles west of Tabriz, are sometimes called “Serapi carpets.”

By 1100 A.D., in the eastern Turkic language, sarapay meant “a noble-man’s robe.”

By 1300 A.D., sarapai had a parallel connotation in Old Russian, where it referred to

“A man’s long caftan having a special cut worn by governors of provinces in ancient Russia.”

By 1100 A.D., in the eastern Turkic language, sarapay meant “a noble-man’s robe.” By 1300 A.D., sarapai had a parallel connotation in Old Russian, where it referred to “A man’s long caftan having a special cut worn by governors of provinces in ancient Russia.”

In modern Russian, sarafan (сарафан) refers either to a jumper or pinafore worn

as a traditional folk costume by girls and women. Sarapi was probably introduced to Spain by Jewish textile merchants traveling back and forth between the eastern Mediterranean and the Iberian Peninsula. See Edgar C. Polomé, et alia, Languages and Cultures, 1988, for more information regarding the word sarapi.

In modern Russian, sarafan (сарафан) refers either to a jumper or pinafore worn as a traditional folk costume by girls and women. Sarapi was probably introduced to Spain by Jewish textile merchants traveling back and forth between the eastern Mediterranean and the Iberian Peninsula. See Edgar C. Polomé, et alia, Languages and Cultures, 1988, for more information regarding the word sarapi.

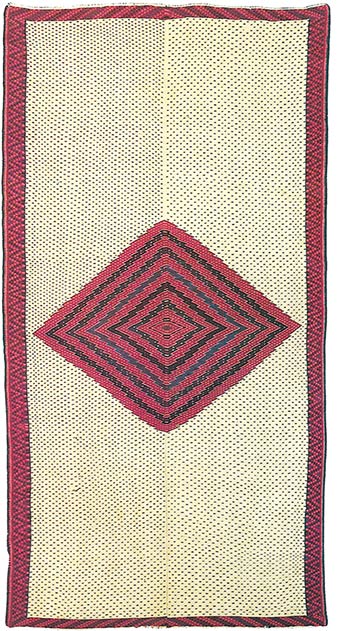

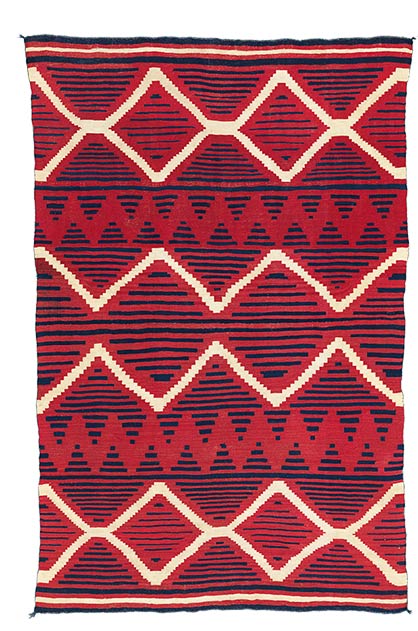

Between 1700 and 1800, in Colonial Mexico, the Saltillo serape became a garment of prestige and a high value trade item. Between 1800 and 1840, a different style of serape, known as the “Serape-Navajo,” became a garment of prestige and a high value trade item throughout the Rio Grande Valley and the southwest. The two blankets illustrated above are, (left), a classic Saltillo serape, circa 1800, and (right), the Kahlenberg Serape, Navajo, circa 1840, currently in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In Commerce of the Prairies, 1844, the explorer-journalist Josiah Gregg wrote one of the earliest published accounts of the Navajo and their serapes:

They reside in the main range of the Cordilleras, one hundred and fifty to two hundred miles west of Santa Fe, on the waters of the Rio Colorado of California, not far from the region, according to historians, from whence the Aztecs emigrated to Mexico; and there are many reasons to suppose them direct descendants from the remnant, which remained in the north, of this celebrated nation of antiquity. Although they live in rude jacales, somewhat resembling the wigwams of the Pawnees, yet, from time immemorial, they have excelled all others in their original manufactures; and as well as the Moquies [Hopis], they are still distinguished for some exquisite styles of cotton textures, and display considerable ingenuity in embroidering with feathers the skin of animals, according to their primitive practice. They now, also, manufacture a singular species of blanket, known as the Sarape-Navaho, which is of so close and dense a texture that it will frequently hold water almost equal to gum-elastic cloth. It is therefore highly prized for protection against the rains. Some of the finer qualities are often sold among the Mexicans as high as $50 or $60 each. [Italics added.]

During the 1840s, $50 in gold was five months’ pay for a colonel in the United States Army. Fifty buffalo hides, twenty horses, ten rifles, or a house in Santa Fe could each be purchased for $50 in gold.

The following quotes about Navajo serapes are by Dr. Joe Ben Wheat. Between 1953 and 1988, Wheat (1916-1997) was Professor of Archaeology at the University of Colorado in Boulder, and first Curator of Anthropology at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, also in Boulder Wheat’s quotes about Navajo serapes are listed on Page 138 in Wheat and Hedlund, Blanket Weaving In The Southwest, 2003. Dates in parentheses refer to either spoken or written statements made by Wheat, prior to publication of Blanket Weaving In The Southwest. After Wheat’s death, in 1997, Wheat’s spoken and written statements were selected for publication by Dr. Ann Lane Hedlund, Wheat’s student and co-author. All spellings in Wheat’s statements are Wheat’s spellings.

“The period from circa 1800 to the early 1860s is usually known as the Classic Period…The majority of classic sarapes had a ground of crimson... Designs were worked in indigo blue and white… Rarely were other colors used.”

“The designs consisted of striped, stepped or terraced triangles, hollow or solid terraced diamonds, or zigzags arranged in rows or zones so as to compose an overall pattern. Frequently, the field was divided into three or five zones, but the patterns of one zone often merged with, or reflected that of, the next. The end zones often had quarter-diamonds at the corners and one or more half-diamonds in between… Occasionally, a network of large hollow diamonds covered the entire center of the sarape and might have smaller figures nested in those diamonds across the center. Negative figures were often made by the placement of the terraced figures and the contrast of the blue and white colors… (Wheat 1996b.)”

“The sarapes woven by the Navajo during the six decades between Massacre Cave in 1804 and the Long Walk which led to Bosque Redondo in 1863 mark the greatest achievement in the long history of Navajo weaving. The Classic Sarape was the culmination of a century and a half of progress, of the growth of a textile tradition. (Wheat 1988d.)” [Italics added.]

“By 1800, the striped form of decoration gave way, in the finest blankets, to a system based on the manipulation of terraced triangles and diamonds derived from designs previously used on [Navajo] basketry. Zigzag stripes, large and small diamonds, solid or hollow, and diamond nets are but elaborations of these basic elements, made complex by their arrangement, the alternation of colors…and the relationship between positive units and negative spaces between. By 1860, these designs tended to become smaller, less bold, and… confined in narrow bands on a panel of white or other neutral color, but occasionally very elaborate compositions were woven. (Wheat 1978a:23).”