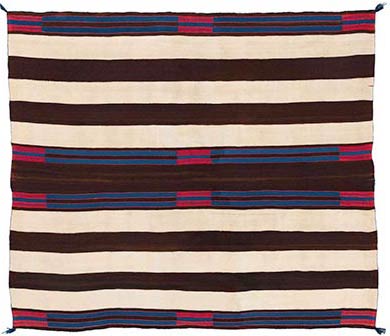

#2. A Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo circa 1840, also known as the Chantland Bayeta First Phase. The first phase measures 58 inches long by 68 inches wide, as woven. The first phase was acquired in 1870 by John Chantland, the Postmaster of Mayville, Dakota Territory. Chantland also owned a general store in Mayville. He accepted the first phase in payment for groceries. The first phase remained in Chantland’s family for the next one hundred and forty-two years.

In February of 2012, Loren Krytzer, of Antelope Valley, California, consigned the Chantland First Phase to John Moran Auctioneers in Altadena, California. Krytzer is the great-great grandson of John Chantland.

On June 19, 2012, the Chantland First Phase sold for $1,800,000, buyer’s premium included, at John Moran’s Auctioneers in Pasadena, California. As of May, 2023, $1,800,000 stands as the auction record for a Navajo blanket. The buyer was the Donald Ellis Gallery, of New York.

In 2016, the Chantland First Phase was sold by the Donald Ellis Gallery to Valerie and Charles Diker, of New York. Between 2018 and 2021, the Chantland First Phase was on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, by loan from the Dikers.

The first phase is illustrated in Baer, The Chantland Blanket, A Navajo Masterpiece, 2012. The first phase is illustrated as Figure 16 in Torrence, Art of Native America, The Charles And Valerie Diker Collection, 2018.

Due to its record price at auction, and to its exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, the Chantland First Phase is one of two Navajo first phases that qualify as candidates for the most famous first phase in the world. The other candidate is the Berlant First Phase.

Above: The Chantland Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

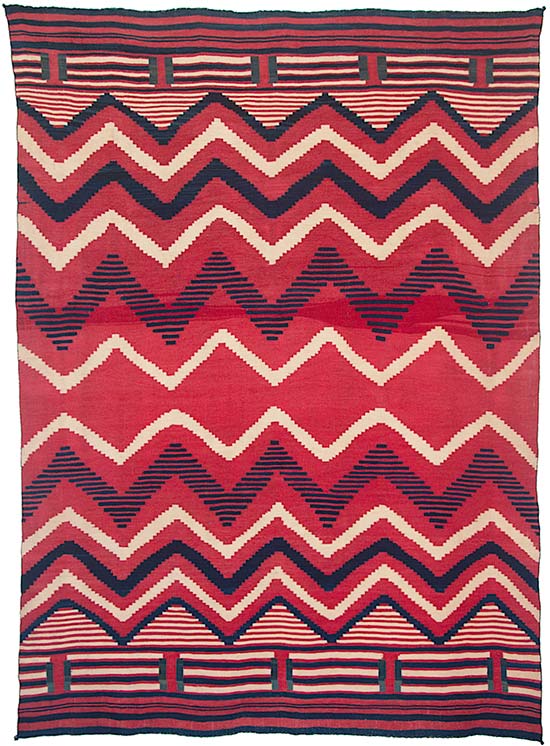

Below: The Berlant First Phase, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1840.

Navajo first phases chief’s blankets woven in the man’s style have alternating brown and white bands in the fields above and below their brown central panels. First phases woven in the woman’s style have thin, alternating stripes in the fields above and below their brown central panels.

In both the man’s and woman’s styles, Ute Style first phases have pairs of blue stripes inside their brown bands and brown central panels, but no red stripes.

In both the man’s and the woman’s styles, bayeta first phases have pairs of blue stripes inside their brown bands and brown central panels, and thin red stripes.

There are less than seventy-five classic (pre-1865) man’s style first phases in museum and private collections. Approximately sixty are Ute Style first phases. Approximately fifteen are bayeta first phases.

There are less than twenty-five classic (pre-1865) woman’s style first phases in museum and private collections. Less than fifteen are Ute Style first phases. Less than ten are bayeta first phases.

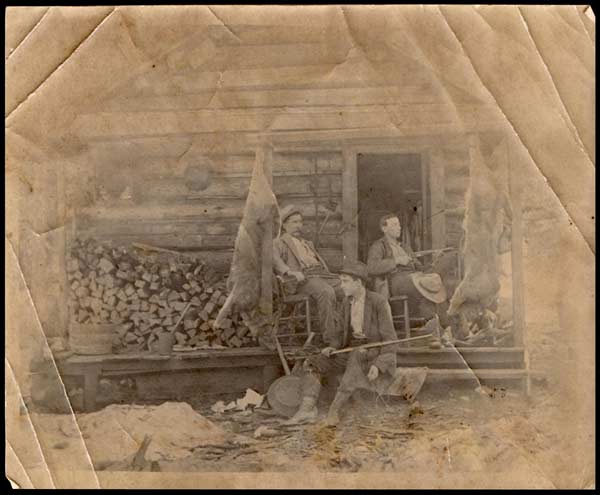

An 1870s photograph of John Chantland shaking hands

with an unidentified woman in Mayville, Dakota Territory.

An 1870s photograph of John Chantland shaking hands with an unidentified woman in Mayville, Dakota Territory.

An 1870s photograph of the Chantland family grocery store

in Mayville, Dakota Territory. John Chantland is seated on the right,

holding a rifle, with his hat on his knee.

An 1870s photograph of the Chantland family grocery store in Mayville, Dakota Territory. John Chantland is seated on the right, holding a rifle, with his hat on his knee.

Upper Left: A Classic First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1830

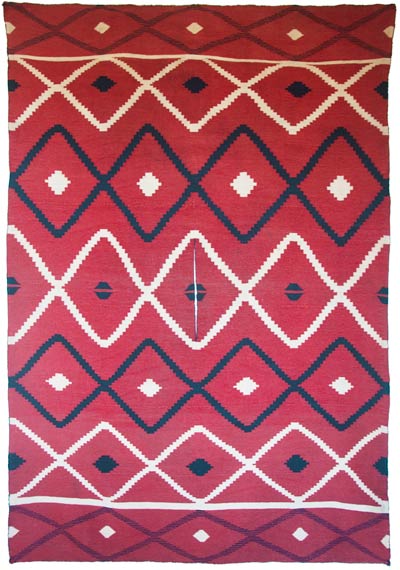

Upper Right: A Classic Bayeta Second Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850

Lower Left: A Classic Bayeta Third Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1850

Lower Right: A Classic Chief’s Blanket Variant, Ute Style, Navajo, circa 1840

In nineteenth century Navajo culture, weaving a copy of a blanket you’d already woven was taboo. The taboo led to innovation. Innovation became a hallmark of classic Navajo weaving. Between 1830 and 1860, Navajo weavers added design elements to the bands and stripes of their chief’s blankets. Thin red stripes were an early innovation, followed by horizontal rectangles and terraced diamonds.

Since the 1860s, Anglo-Americans have categorized Navajo chief’s blankets according to their designs. Chief’s blankets with horizontal bands and stripes, but no designs, came to be known as “first phases.” Chief’s blankets with concentric squares or horizontal rectangles were called “second phases.” Chief’s blankets with terraced diamonds were called “third phases.” Chief’s blankets with combinations of horizontal rectangles, concentric squares, terraced diamonds, or other geometric designs were called “variants.”

While there are no words in Navajo for “first phase,” “second phase,” “third phase,” or “variant,” repetition of these terms by Anglo-Americans made them a part of the vocabulary now in use by auction companies, collectors, dealers, and scholars when we talk about Navajo chief’s blankets. Like the blankets themselves, the terms we use to describe them evolved over two centuries of interactions between Navajo, Spanish, Pueblo, and Anglo-American cultures.

During the nineteenth century, first phases were unpopular with Anglo-Americans, who thought they were too simple. Between 1900 and 1930, the Fred Harvey Company bought and sold many of the classic Navajo blankets now in museum and private collections. Harvey Company ledgers show that, between 1900 and 1930, classic third phases sold for higher prices than first phases or second phases.

By 1975, the price structure had inverted. First phases were selling for twice as much as second phases, third phases, or variants. On November 28, 1989, Sotheby’s, New York, sold a Classic Bayeta First Phase Chief’s Blanket, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the Walentas Bayeta First Phase, for $522,500. At that time, neither a second phase, a third phase, nor a variant had sold for more than $100,000, either at auction or through a private sale. For the next twenty-three years, until the sale of the Chantland Bayeta First Phase for $1,800,000, in June, 2012, $522,500 stood as the auction record for a Navajo blanket.

The Walentas Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

The first phase measures 57 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven.

Sold by Sotheby’s, New York, for $522,500, on November 28, 1989.

In the collection of David Walentas, New York.

The Walentas Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840. The first phase measures 57 inches long by 76 inches wide, as woven. Sold by Sotheby’s, New York, for $522,500, on November 28, 1989. In the collection of David Walentas, New York.

A Classic Bayeta Serape, Navajo, circa 1840, also known as the de Menil Serape.

The serape measures 71 inches long by 55 inches wide, as woven.

“The Navajoes… are not in a state of coveting herds of sheep, as their own are innumerable. They have increased their horse herds considerably; they sow much and on good fields; they work their wool with more delicacy and taste than the Spaniards. Men as well as woven go decently clothed; and their Captains are rarely seen without silver jewelry; they are more adept at speaking Castilian than any other Gentile nation; so that they really seem ‘town’ Indians much more than those who have been reduced…”

- Fernando de Chacon, Governor of New Mexico, in a letter dated July 15, 1795, to Pedro de Nava, Military Commander of Chihuahua. (Chacon’s letter is quoted on Page 132 in Amsden, Navajo Weaving – Its Technic and History, 1934.)

By 1850, the Navajo had become one of the wealthiest tribes in North America. The Navajo were prosperous because they were actively engaged in commerce with the Plains and Prairie tribes, and with Mexican and Spanish explorers, merchants, and ranchers.

Demand for Navajo chief’s blankets came from high-ranking members of the Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota. Shoshone, and Ute Tribes. The term “Ute Style first phase” came from the Utes’ preference for first phases woven with alternating brown and white bands, and pairs of blue stripes inside their brown bands and brown central panels—with no red stripes. Demand from the Mexicans and the Spanish was for the Navajo serape. Woven longer than wide, with a red field and foreground designs in blue and white, bayeta serapes were the most valuable blankets in North America.

While it’s not possible to identify regional styles for classic chief’s blankets and classic serapes the way it is for twentieth century Navajo floor rugs, it is reasonable to assume that bayeta serapes were woven closer to Santa Fe and Taos, where bayeta was readily available to Navajo weavers. By the same token, the majority of classic first phases were probably woven further north, in and around Monument Valley and the Four Corners, where bayeta was less available to Navajo weavers. Given that the Utes were the Navajo’s immediate neighbors to the north, the term “Ute Style” supports this assumption.

An Early Classic Poncho Serape, Navajo, circa 1830.

The poncho serape measures 71 inches long by 52 inches wide.

The red field of the poncho serape was woven with raveled bayeta

piece-dyed with lac. All of the bayeta in the poncho serape was raveled

from the same bolt of bayeta.

The red field of the poncho serape was woven with raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. All of the bayeta in the poncho serape was raveled from the same bolt of bayeta.

“Bayeta” is a term used to describe a red, machine-woven woolen flannel produced in England and Spain between 1650 and 1860. At the woolen mills in Manchester and Seville, lengths of white woolen flannel were machine-woven and then piece-dyed in vats of cochineal, lac, or combinations of lac and cochineal.

Bolts of red bayeta were traded in Santa Fe as early as 1690. Throughout the eighteenth century, bayeta was regarded as a high value trade item. In Navajo Weaving, Its Technic and History (1934), Charles Avery Amsden refers to The Last Will and Testament of Don Diego de Vargas, dated 1704. After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Spain reconquered New Mexico, in 1694. de Vargas was the military leader of the Spanish Reconquest. de Vargas is often referred to by Hispanic New Mexicans as either “the Conqueror,” or “the Conqueror of New Mexico.” In his will, de Vargas left nine varas [yards] of bayeta to his niece.

A Navajo woman carding wool by her hogan, circa 1890.

Photographer unknown.

“It seems anomalous to me that a nation living in such

miserably constructed mud lodges should, at the same time,

be capable of making probably the best blankets in the world.”

“It seems anomalous to me that a nation living in such miserably constructed mud lodges should, at the same time, be capable of making probably the best blankets in the world.”

- Lieutenant James H. Simpson, The Navajo Expedition of 1849.

In 1844, in Commerce of the Prairies, the American journalist Josiah Gregg, wrote about the Navajo and their blankets:

“They reside in the main range of the Cordilleras, one hundred and fifty to two hundred miles west of Santa Fe, on the waters of the Rio Colorado of California, not far from the region, according to historians, from whence the Aztecs emigrated to Mexico; and there are many reasons to suppose them direct descendants from the remnant, which remained in the north, of this celebrated nation of antiquity. Although they live in rude jacales, somewhat resembling the wigwams of the Pawnees, yet, from time immemorial, they have excelled all others in their original manufactures; and as well as the Moquies [Hopis], they are still distinguished for some exquisite styles of cotton textures, and display considerable ingenuity in embroidering with feathers the skin of animals, according to their primitive practice. They now, also, manufacture a singular species of blanket, known as the Sarape-Navaho, which is of so close and dense a texture that it will frequently hold water almost equal to gum-elastic cloth. It is therefore highly prized for protection against the rains. Some of the finer qualities are often sold among the Mexicans as high as $50 or $60 each.”

In 1844, $50 in gold was five months’ pay for a colonel in the United States Army.

Fifty buffalo hides, twenty horses, ten rifles, or a house in Santa Fe could each be purchased for $50 in gold.

In 1844, $50 in gold was five months’ pay for a colonel in the United States Army. Fifty buffalo hides, twenty horses, ten rifles, or a house in Santa Fe could each be purchased for $50 in gold.

A Classic Bayeta Serape, Navajo, circa 1840.

The serape measures 71 inches long by 54 inches wide, as woven.

The serape’s red yarns are raveled bayeta piece-dyed with pure lac.

“… the Navaho unravel fine scarlet blankets of English manufacture, the threads of which are then used in weaving of their own.”

John Russell Bartlett, The Progress of Ethnology, 1847

Bayeta was a valuable trade item in Santa Fe because of demand from the Navajo.

The Navajo placed a high value on bayeta because their chief’s blankets and serapes were the most expensive wearing blankets in North America. Demand for classic red field serapes came from the Spanish. Demand for classic chief’s blankets came from the Plains and Prairie Tribes, notably from high-ranking members, or chief’s, of the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, Sioux, and Ute Tribes.

Bayeta was a valuable trade item in Santa Fe because of demand from the Navajo. The Navajo placed a high value on bayeta because their chief’s blankets and serapes were the most expensive wearing blankets in North America. Demand for classic red field serapes came from the Spanish. Demand for classic chief’s blankets came from the Plains and Prairie Tribes, notably from high-ranking members, or chief’s, of the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, Sioux, and Ute Tribes.

Due to their lack of effective mordants, and their inability to boil water in large enough quantities of to strip lanolin from their fleeces, Navajo weavers could not

dye their handspun white yarns with cochineal and create red handspun yarns. The weavers’ primary source of red yarn was to cut bayeta flannel into strips, ravel threads of red yarn from the cut strips, and re-weave the raveled red yarns into their chief’s blankets and serapes.

Due to their lack of effective mordants, and their inability to boil water in large enough quantities of to strip lanolin from their fleeces, Navajo weavers could not dye their handspun white yarns with cochineal and create red handspun yarns. The weavers’ primary source of red yarn was to cut bayeta flannel into strips, ravel threads of red yarn from the cut strips, and re-weave the raveled red yarns into their chief’s blankets and serapes.

Classic Navajo serapes tend to have backgrounds of red bayeta, with blue and white foreground design elements. When raveled red yarns appear in classic Navajo chief’s blankets, they appear either as thin stripes, in first phases, or as foreground design elements in second phases, third phases, and variants. Today, raveled bayeta is commonly referred to either as “raveled yarn” or as “raveled red.”

The center of the Chantland Bayeta First Phase, Navajo, circa 1840.

In the Chantland First Phase, the red yarns are raveled bayeta piece-dyed with lac. The blue yarns are handspun Churro fleece dyed in the yarn with indigo. The brown yarns and the white yarns are un-dyed handspun Churro fleece.

Lac dye, or kerria lacca, is a fermented form of cochineal. Between 1800 and 1860, lac was imported by the British Empire from their colony in Bengal, India.

One of the ways we’re able to circa date classic Navajo blankets is by dye analysis of both their raveled red yarns and their red European machine-spun knitting yarns, also known as Saxony yarns. Spanish woolen mills dyed their bayeta fabric exclusively with cochineal, which the Spanish crown imported from Colonial Mexico. Cochineal is the pulverized form of the dried larvae of ladybugs that lay their eggs on the leaves of the nopal cactus in the Mexican cordillera. Cochineal was harvested by the Tlaxcalan Indians before and after the arrival of Cortez and the Spanish, in 1509. After silver, cochineal was Mexico’s second-largest export to Spain.

While the English dyed some of their red bayeta with lac, the English also dyed their red bayeta either with cochineal, or with combinations of cochineal and lac. The English dye industry was located in Manchester, England. The woolen fabric mills in Manchester were supplied with cochineal for their dye works by English pirates, who obtained cochineal by raiding Spanish galleons in the Atlantic, usually off the coast of Cuba. For a more detailed account of the differences between the Spanish cochineal trade and the British trade in lac and cochineal, see The Perfect Red by Amy Butler Greenfield.

Above: The Chantland First Phase in June, 2012, before cleaning.

Below: The Chantland First Phase in July, 2012, after cleaning.

The upper photograph of the Chantland First Phase was taken in June, 2012, when the first phase sold at auction. At that time, the Chantland First Phase was in excellent condition with less than 1% restoration. Minor stains were visible in the lower left quadrant. Corner tassels were 75% worn away. Side selvages and top and bottom edge cords were 99% original.

In July, 2012, the Chantland First Phase was cleaned and restored by Robert Mann Oriental Rugs in Denver. The cleaning process removed all of the stains. Corner tassels and side selvages were stabilized, using the first phase’s original yarns.